What will it take to shift our moral compass from hostile dehumanisaton to empathetic humanitarian concern for those desperate 600 children, women and men fleeing the persecution of life and livelihood insecurity in that slowly capsising fishing trawler? As they drowned off the Peloponnesian shore, what did they think of the inhumanity of policies that held back the Greek coast guard from rescuing them?

Could they have expected anything different when populist xenophobic politics around migration have led to the rise of hard Right regimes such as those of Georgia Meloni and the strategy of standoffs with humanitarian rescue ships in Italy, of Rishi Sunak’s policies of detention, deportation and holding in transit in Rwanda illegal migrants who have reached UK shores, or of Donald Trump’s barricading of borders to enforce ‘Remain in Mexico’ policy.

Lest we get comfortable in smug self-righteousness over the ‘blame game’ of the migration/refugee crisis and castigate colonial rapacity, which structurally beggared post-colonial economies and today’s neo liberalism, which produces growth, but deepens inequality. And add to that, geo-politics that stoke violent conflicts that produce Internally Displaced People (IDPs) and refugees as well as the racialisation of discriminatory international regimes of protection and care. But what about our own ethics, our humanity when it comes to the 2,44,000 Afghan, Rohingya, Chin, Chakma, Sri Lankan and Tibetan refugees seeking protection and care in India?

Two years ago, Rokeya (name changed), a 14-year-old Rohingya Muslim girl—an asylum-seeker and a likely victim of cross border trafficking—was in a shelter house in Assam. In April 2021, she was taken to the More-Manipur border for deportation to Myanmar. That her parents were in Bangladesh and her home village had been burnt down seemingly made no difference to the peremptory executive decision to deport her. It was two months after the February 2021 military coup and the widespread violence which followed in Myanmar. But Roekya, without a passport and valid visa, was deemed an ‘illegal migrant’ in violation of the Foreigners Act, (1946) and therefore was to be deported. Despite a pending legal appeal, the child was marched to the border. It was the Myanmar immigration authorities who declined to admit her as it was ‘inappropriate’ during the pandemic to open up the border.

Rokeya’s case exposes that India’s lack of a national refugee law places women and girls at disproportionate risk of trafficking due to their physical, economic and legal precarity. India does not recognise the separate category of refugees who are thereby at risk of being conflated with illegal migrants and other aliens and criminalised under the omnibus Foreigners Act.

Reinforcing the precarity of the predicament of refugees is the fact that India is not a signatory to the UN Refugee Convention 1951 and the 1967 Protocol, although it is bound by its treaty obligations under international human rights law.

Rokeya’s vulnerability revealed serious flaws in the framing of India’s Anti-Trafficking Bill (2021) in addressing non-nationals. This was despite UNHCR’s recommendation that the law include “specific safeguards for persons in need of international protections … and de-

penalise (their) irregular entry and stay”. The bill decrees repatriation in the case of non-citizens, indifferent to the causes propelling forced migration, and denies agency.

Rokeya’s predicament foregrounds the complexity of mixed migration flows and the blurring of the distinction between regular and irregular migration, especially when hostile entry regimes drive desperate people fleeing persecution, and dreaming of safety and a better life, to use the same channels of flight as human smugglers and traffickers. Cross- border movements have become so mired in the securitised and criminalised discourses about ‘illegal migration’ that it altogether eschews the possibility of viewing an asylum seeker or a trafficking victim from a humanitarian and human rights lens.

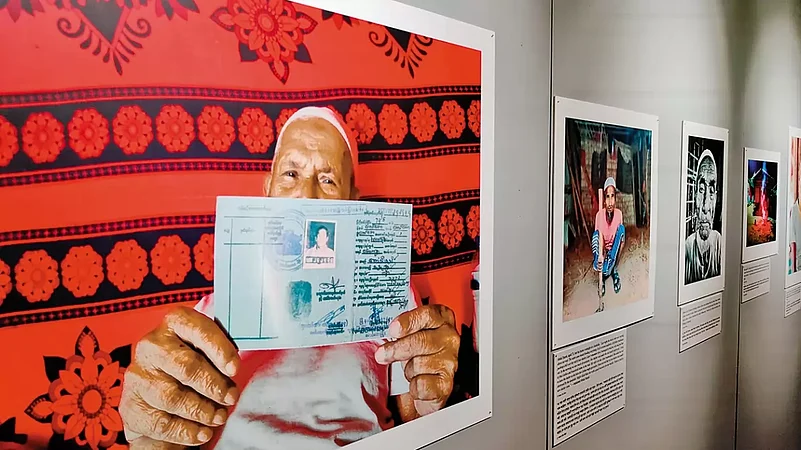

Importantly, Rokeya’s ethno-religious identity as a Rohingya Muslim targeted her. In a significant shift of policy in 2017, the government classified the country’s then estimated 40,000 Rohingya as ‘illegal migrants’ and ordered law enforcement agencies to initiate deportation processes. This was regardless of the fact that over 18,000 Rohingyas possessed UNHCR-issued refugee status determination cards, and allegations impugning terror links of Rohingya refugees had been repeatedly refuted by official agencies. More than 40 Rohingya women, men and children have been deported and over 300 Rohingyas are locked up in detention centres awaiting deportation.

Ironically, the same Rohingya refugees were part of the basket of refugees who had been beneficiaries of the Indian government’s accommodative policy of issuing Long Term Visas. Deepening diplomatic, security and economic relations with Myanmar’s government produced pragmatic ambiguity towards the victimisation of the Rohingyas fleeing torture, mass rapes and brutal killings.

Moreover, rising populist ethno religious nationalism within the country has turned the issue of refugee protection into a selective religious and nationalist preference, and reinforced by the NRC plebiscitary process and the CAA.

The foundational principle of the international refugee protection regime, non–refoulement, (non-expulsion) recognised as customary law and jus cogens came under pressure. The government insisted that the principle of non-refoulement did not apply as India was not a signatory to1951 Convention.

The judiciary through various case laws had compensated for legal ambiguity and had upheld non-refoulement, invoking Article 21 and thereby requiring determination of whether the procedure for expulsion was “just, fair and reasonable”. However, as Rajeev Dhavan, an authority on refugee law, assessed “there is no settled law or predictable policy of a due process regime for either status determination or deportation of refugees”.

The framing of the issue as one of illegal immigration and not flight from a situation of persecution, made it difficult for Rohingyas to access constitutional protections that were afforded to other groups in the past. In a benchmark case, the Supreme Court in 2018 and 2021 declared non-refoulement did not apply and allowed deportations.

India’s ad hoc refugee policy/praxis is structured around the politicised binary of ‘good refugee, bad refugee’, with religious nationalism becoming the arbiter. Arguably, the moral human rights and humanitarian claims of the most recent mass influx from Myanmar of co-ethnic Chin Christian refugees across the porous Northeast border are sifted through not only securitised and foreign policy filters but also communal ones. Not surprisingly then that refugee communities, especially the recent flow of Afghan Muslim refugees fleeing the 2021 Taliban takeover, worry that if India’s relations with Taliban-ruled Afghanistan are normalised, it might mean exit for them.

The absence of a national refugee law makes for an ambiguous regulatory regime which tends to be arbitrary, ad hoc and even discriminatory. India declined to adhere to the 1951 Convention viewing it as eurocentric, a cold war tool, and imbued with a racist global north-south bias. Building on refugee studies, scholar BS Chimni’s influential critique of the ‘myth of difference’ of refugees from Afro-Asia, feminist scholar Heather Johnson draws attention to the feminisation of the representation of the refugee subject—women-child dyad.

It provides the moral logic for what Johnson contends are three shifts in the imagining of the refugee subject— ‘racialisation, victimisation, and feminisation’ within a discourse of de-politicisation and naturalisation of denial of agency to the refugee subject. Each shift has contributed to changing practices and policies of the international protection regime from a ‘preferred solution’ of integration and resettlement to one of return and repatriation.

The de-politicisation and disempowerment of refugee woman as a victim has meant her exclusion from decision- making and further marginalisation. It has reinforced victim/dependent status on abusive husbands and inattention to the structural needs of refugee women. Field visits to refugee settlement clusters even within conservative patriarchal societies evidence the resilient agency of refugee women as people looking to carve out their own destinies.

Rohingya refugee Mumtaz Begum (22) refuses to be a passive victim, thereby shocking her neighbour Mehrunissa (60) who is convinced Mumtaz practices Black Magic. “Which kind of girl survives a dead family, a runaway husband and still paints her nails red”. The entrance to her shanty in Jammu is adorned with sequin embroidery patches, an advertisement of her needlework skills. It got her a contract from a local boutique. She is an abandoned, childless wife who earns her own living, rejecting the community’s handouts.

Afghan Sikh refugee Manpreet Kaur (34), a victim of brutal domestic abuse, betrayed by the local Gurudwara authorities into losing her two infant sons in a divorce settlement, runs a tailoring business in Tilak Nagar, supporting her parents and herself. The material reality of refugee women’s experiences challenges the default practice of ‘going through the men’ and thereby silencing her voice, and increasing her vulnerability.

Adding to her predicament is the tendency on the part of protection and humanitarian staff, whose socio-historical imaginaries are shaped by colonial or northern anthropologists, to use particularist cultural explanations of consent norms for gendered persecution and discrimination.

Gendered persecution is an add-on to the international refugee regime structured around the prototype of a male refugee. Translating the legal recognition of sexual violence as a politically motivated public violation, and gender-based persecution as institutionalised gender apartheid into operational protocols for filtering asylum requests has proved challenging.

Interviews with Afghan female-headed refugee families and the reality of single girls fleeing persecution reveal a troubled refugee status determination process. Will the plea of life-threatening vulnerability and gender persecution violations be dismissed as customary practice in a socio-cultural milieu that sanctions such sale/marriages and views girls/women as expendable commodities? Returning to our ethical responsibility and humanity, is the country’s policy of strategic ambiguity and the ethics of care and concern sufficient to provide protection? Chimni’s warning is discomfiting. “In modern societies, a void in the legal system is not filled by an ethics of care and responsibility. The absence of law is seen as a signal to omnipresent state agencies that a particular class of persons exists only at the mercy of the state”.

Rita Manchanda is a rights based peace and conflict studies scholar

(This appeared in print as 'Humans'...Like Us')