Standing in the scorching heat beside the gate of his old-style three-room mud house, Pravin Madhukarrao Patil wonders what is next for him. “My father killed himself two years ago due to a Rs 5 lakh debt that caused him more stress than he could handle,” says Patil, a 39-year-old resident of Salora village, 25 km from Maharashtra’s Amravati city. “He told us he was going outside for some work. When he did not return a few hours later, I and my wife went looking for him. We found him hanging on a jamun tree near our farm.”

Looking through his moist eyes, Patil says his father had borrowed the money to grow chana (gram). The three left behind—Patil, his wife and his mother—still await Rs 70,000 they say they were promised as compensation from the state government. “We were told it will take seven more years, and we have no clue why it should take so long,” Patil adds. The Maharashtra government has a scheme under which it gives Rs 1 lakh to the kin of farmers who died by suicide.

According to National Crime Records Bureau data, the state recorded 169,868 suicides from 2014 to 2022, of which nearly 30 per cent (57,160) were of farmers. The causes ranged from erratic weather patterns, generational debt among new-age farmers, changes in climate patterns and lack of alternative employment for the farmers’ children. And, while the annual suicide rate in India was 9.7 per 100,000 population in 1995, according to a 2012 research paper published by Amol Dongre and Pradeep Deshmukh with the US government’s National Library of Medicine, which implies 116 suicides per year in Vidrabha with its population of 1.2 million (2011 Census), the actual figure stood at 572 in 2005, 1,065 in 2006 and 600 in 2007. The latest numbers show a more drastic picture. Till June 2024, 557 farmers—170 in Amravati district, 150 in Yavatmal, 111 in Buldhana, 92 in Akola and 34 in Washim—ended their lives in Vidharbha, a report by the Amravati divisional commissioner showed.

Salora has seen 10 suicides in the past three years—each one a breadwinner of the family. The eldest among the few willing to share the story of their “darkest day” is Seshraj Tayade, an octogenarian who lost the youngest of three sons, Giridhar, in April 2022. “My wife was sick at that time,” says Tayade, 81, in a small room in the house he shares with his wife—the very room where Giridhar ended his life. “Giridhar did not have money to buy her medicines, and she was also scheduled for an operation later. He went somewhere and returned with Rs 5,000, telling his mother to buy the medicine. He was already in debt of around Rs 20,000.”

According to NCRB data, the state recorded 169,868 suicides between 2014 and 2022, of which nearly 30 per cent (57,160) were of farmers.

Tayade says Giridhar hated to be in debt. “After that, I and my wife sat outside the house. When Giridhar, even after a long time, did not come out, we went to check and found the door locked from inside. We peeped from the window and saw him hanging from the ceiling fan. My wife collapsed on the spot,” recalls Tayade.

With farmer suicides rising year after year, Tayade says that the numbers mean nothing to politicians. After spending most of his life in Salora and Nashik, he says he has seen numerous politicians promising the moon when they come for votes but ending up doing nothing. “I have voted for nearly 12 Lok Sabha and assembly elections to date. Nothing has worked for me, I still live with disparity and pain,” he says.

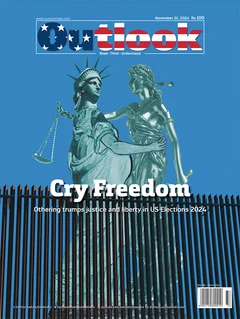

During rallies in the Vidarbha region for the Lok Sabha election, politicians refrained from talking about farmer suicides. Even Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who promised to accelerate development and usher in a new era of progress while outlining his vision for Vidarbha, Maharashtra and the nation at his first rally, in Ramtek on April 14, did not mention the suicides. Although the issue is almost entirely missing from discussions about the assembly election due on November 20 (results will be announced on November 23), the Opposition has been pointing fingers at the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led government at the Centre and the Eknath Shinde-led government in Maharashtra on agrarian policies leading to suicides.

The causes ranged from erratic weather patterns, generational debt among new-age farmers, changes in climate patterns among others.

At a presser on October 7, Jairam Ramesh, All India Congress Committee general secretary in charge of Maharashtra and member of the Rajya Sabha, questioned the BJP government on its response to the high number of farmer suicides. Then, on October 21, Congress President Mallikarjun Kharge called the BJP “the biggest enemy of Maharashtra’s farmers” and said farmers will only benefit from removing the “double-engine government” from power. In a post in Hindi on social media platform X, Kharge said the promise of making the state drought-free is a jumla (rhetoric)—a 20,000 farmers had already committed suicide. The promise of Rs 20,000 crore water grid turned out to be false,” he added.

Though manifestos replete with promises offer no solution to farmer suicides, the ruling Mahayuti alliance announced a farm loan waiver, raised the annual aid to farmers under the Shetkari Samman Yojana from Rs 12,000 to Rs 15,000, and offered a 20 per cent subsidy on the minimum support price (MSP) in its manifesto. The Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA), the Opposition alliance, said it would waive farm loans of up to Rs 3 lakh and provide Rs 50,000 as aid to farmers regular in the repayment of loans.

According to Manisha Madhava, head and professor, department of political science, S.N.D.T Women’s University in Mumbai, however, issues concerning the people and the state have been on the back burner, while those that gather more social response faster are on the front. “Elections are becoming more hyperlocal, where each party or leader is looking at saving their bastion instead of the people’s issues coming to the fore,” Madhava says.

Farmer suicides in Vidharbha have been discussed by politicians, academics, non-governmental organisations (NGO) and sector experts for more than 20 years, while the central and state governments have provided relief packages that have been unable to solve the larger issues. An April 2007 report published by an NGO, Green Earth Social Development Consulting, after an audit of state and central relief packages for Vidarbha showed that farmers’ demands and consultations with civil society organisations and local bodies had not been taken into account. Besides a farmer helpline and direct financial aid, scarcely anything new was being offered.

Farmers in Maharashtra were badly hit by the ban on exports of onions from December 2023 to March 2024. The Centre had enforced the ban to address shortage in domestic supply and secure a steady and affordable supply for consumers. India is the second largest onion-producing country, just behind China. According to data from the Department of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, India’s total onion production for 2023-24 is expected to be around 24.21 million tonnes after falling from 31.68 million tonnes in 2021-23 and 30.20 million tonnes in 2022-23. Maharashtra is a major onion-producing state, leading the pack with around 30-35 per cent of total production, followed by Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana and Telangana.

The Nashik belt in north-west Maharashtra is one of India’s richest regions producing quality red and brown onions. Shivaji Namdev Nikam, 71, from Teesgaon near Nashik, rues that most of his onion produce rotted due to excessive rains in August and September 2023. “The crop on nearly half the land was damaged from the roots, making it unsaleable. My initial calculations showed a loss of Rs 10,000, which later spiked to Rs 80,000,” Nikam says.

On May 4, ahead of general elections, the Centre lifted what was the longest of numerous export bans farmers have experienced in the past decade. Between 2014 and 2019 alone, the government halted exports 17 times to prevent prices from escalating, invoking the Foreign Trade (Development and Regulation) Act, 1992. Between 2020 and 2023, export was allowed with a 40 per cent duty, which farmers found tolerable.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

With the parties betting their way on the top step, farmers in Nashik and Amravati today are hoping someone would give their grievances and suggestions an ear. Vinayak Shinde, 37, a second-generation farmer, wishes to discuss a plan that could help ease farmers’ distress. “I have met leaders like (former CM) Devendra Fadnavis in the past six-seven years and mentioned a plan for a solution. They promised to listen but nothing happened,” says Shinde, who has just started to till the land for the rabi season’s onion farming. Doubling as a social activist, he has communicated with hundreds of farmers in and around Nashik on getting the right price for their produce. “This is our main demand,” he says. “Many actions are happening on the climate front that have damaged our crops. Giving us the right price could help solve many of the issues.” Virendra and Ravindra Langde, who lost their father in 2022, have the same demand. “He died due to stress after getting unfair compensation for his land,” says Shinde. “We demand the best price for the produce. This year, we lost more than Rs 50,000 on our soybean produce as we couldn’t afford it with already a debt to repay.”