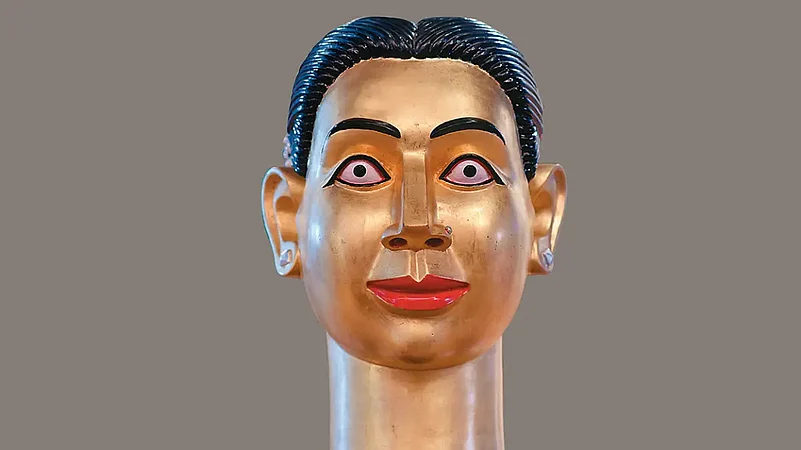

On one of the walls of the museum stands a woman’s bust with a straight gaze that appears to confront many things—rhetoric, unfreedoms, male hegemony, and a narrow view of textbook history that is being rewritten to suit political agendas. This could be the female gaze that casts itself on other female figures in the big hall. The futuristic gaze in the gold-emblazoned bust by Ravinder Reddy emphasises everyday Indian women exuding casual sexuality and encompassing the feminine. This is no sideward glance. It is almost a challenge to the ways of seeing, a reminder almost to see women as subjects and not objects. At this exhibition titled Women and Deities—on display at Bihar Museum in Patna for its 2022 Foundation Day celebrations (it runs through September)—you see more than just relics from the past, or just breasts and butts. You see the feminine and feminist principles fuse in resistance against the hysteria in the name of religion. It’s a timely offering of perspective and hope.

You see a feminist future emerging from the feminine aesthetics of the past, powerful enough to break the glass over what could easily be characterised as feminine, a cultural definition rather than a political one. But all personal is political, whether intended or not. Culture and politics don’t operate in isolation.

The exhibition of 156 artworks, including 10 contemporary ones, spans a period of 2,000 years. They are culled from the museum’s own store. Anjani Kumar Singh, the museum’s director-general, says it’s a tribute to women of India and Bihar.

The statue of the Didarganj Yakshi from the 3rd century BCE, found in Bihar, is testimony to the range of this exhibition, from the divine to the temporal. It traces the position of women and their representation in different eras, in social and political contexts. Like the one of Indrani, the daughter of a demon king, who became a god’s consort.

A 6th century statue in stone excavated from Saraikela in Jharkhand has the goddess holding a child. Also called Shachi, her sexuality defies all attempts at sanitising Hinduism, in which there is no concept of divine blasphemy. It is an orthoprax tradition, not an orthodox one. The pantheon is evidence of that, and in some sense, at loggerheads with the extremely reductive definition of the religion itself.

Section 295 of the Indian Penal Code criminalises insult to religion, allowing up to three years imprisonment and fines for “whoever, with deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings of any class of citizens of India, by words, either spoken or written, or by signs or by visible representations or otherwise, insults or attempts to insult the religion or the religious beliefs of a class.”

In 1996, Bajrang Dal activists attacked a gallery in Ahmedabad for displaying works of Maqbool Fida Husain, on the grounds that they offended Hindus. He had earlier faced court battles, death threats and abuse, after a little-known Hindi monthly from Madhya Pradesh, Vichar Mimansa, accused him of hurting Hindu sensibilities by painting Goddess Saraswati in the nude in 1976. Husain was eventually hounded out of India.

“Her upper garment was the globules of foam and her glorious breasts the sporting rahanga birds. Her romavali, effective in distracting the minds of learned men, was the network of algae. Her beautiful ringlets of braided hair were the rows of bees, and her lengthy eyes, the petals of the blossomed lotus. Her navel, dispelling the heat of those with fever, was the whirlpool churned by the wind… her buttocks were wide, glistening sand banks.”

—Sridhara, comparing the River Yamuna to a courtesan. From The Pasanahacariu of Sridhara: The First Four Sandhis of the Apabhramsa Text. Quoted by Alka Pande in The Eternal Feminine for Bihar Museum’s Women and Deities exhibition curated by her.

But that painting is innocuous compared to the Indian pantheon that is full of unclothed deities, like the stone statue of Lajja Gauri from the 6th century that was found in Kosambi in Uttar Pradesh and is on display.

“There was no fear. This is our history. This is our claim to it,” Singh says. For curator Alka Pande, the exhibition represents—along with beauty and grace—the power of women.

While the representations of women and deities aren’t biased, its viewership could be—moulded as it is by the colonial strategy of casting gender within hierarchies and binaries. But that can be sidestepped, ignored and dismissed. It is feminine and feminist. It challenges and resists.

The exhibition places a statue of a dancing girl among a horde of goddesses from the pantheon that includes pagan goddesses like Mansa Devi, representing a range of polytheism among the masses. And although some have argued that this was organised in a monistic way, there is a stark difference in the way Abrahamic religions look at monotheism. Some might even say they all represent the one god in Hinduism.

Whether the goddesses represent one or many, the exhibition is evidence of empowerment of expression in history, and while many have attributed the feminine principle to such representation, in the laterite statue on display at the exhibition, of the twelve-armed Buddhist female deity Chunda from the 8th century AD, excavated in Odisha’s Cuttack, you see a serpent, a book and a noose, among other objects.

Then there is Hariti, a Buddhist goddess in bronze who was an ogress and devoured children, but became a protector of children after converting to Buddhism. The goddess is not the “other” as Pande notes, becoming an “inseparable entity in the cosmological order of being structured through a fantasy”.

The Dancing Girl from Mohenjo-daro with the decorative headgear in terracotta, from around 2nd century BCE, found in Bihar’s Buxar, is there too, sharing space with the deities. The exhibition is thus an antidote to “othering”, and also to the gender inequality that continues to plague societies, particularly in India.

Museums are repositories of history and can resurrect the suppressed history in today’s world of hate-filled rhetoric. They are physical manifestations of history, and encounters with such a range of artworks representing women and deities—where there isn’t an attempt to make women aspire to become goddess-like that many feminists argue is equating upper-caste Hindu symbolism with femininity—bring up questions of marginalisation and representation.

Here, in the nude figurines of goddesses, there is no such thing as “honour”. In a country of many regressive practices—from female foeticide and a growing obsession with “love jihad”, to honour killings that strip women of their agency—the exhibition is a timely reminder, where evidential history collides with contemporary reality.

(This appeared in the print edition as "The Zeitgeist")