In December 2016, a few weeks after demonetisation, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, while addressing a rally, said: “Jyada se jyada kya kar lenge? Arey hum toh fakeer aadmi hai, jhola leke nikal lenge (What can my opponents do to me? I am a hermit. I will exit with my few belongings)”. While this part of his speech became famous in the following days through social media, it was not the first time that the projected image of a political leader as a fakir or saint got political traction.

Since the days of Mahatma Gandhi, a true leader in India has been considered to be an embodiment of three quintessential features—asceticism, sacrifice and celibacy. Among these, the most powerful tool has been the evocation of sacrifice. As Modi was shown meditating in a cave in Uttarakhand just a few days prior to the declaration of the 2019 General Election results, his persona was viewed from the lens of abstinence—a stage where a person sacrifices the comfort of material life to achieve some high moral ground.

While the portrayal of Modi as a saintly figure is a part of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) decade-long strategy, in the last few years, projecting his spiritual side, spreading the message of love, abandoning material comfort and showcasing a deep engagement in the ideal of ‘sewa’, Rahul Gandhi has emerged as the embodiment of the necessary saintly impulses that seem to counterweight his rival’s projected image.

However, one can’t miss the differences in the evocation of two forms of sacrifices. On the one hand, there are Modi’s references to his personal sacrifices—like leaving his wife for indulging in the service of the nation, echoing Gautam Buddha’s idea of ‘sanyas’; on the other, the martyrdoms of Gandhi family members have never left the mindscape of Rahul Gandhi. Sugata Srinivasaraju, the author of Strange Burden, rightly says that whenever Rahul Gandhi recounts the loss of his family members, he takes a 20-second pause, and then talks about ‘forgiveness’.

Since he joined politics, Gandhi has invoked the sacrifices of his father and grandmother several times. In March this year, when he was disqualified from Parliament, besides updating his status as ‘disqualified MP’, he wrote, “Satya, sahaas aur balidaan—ye humari virasat hai, aur yahi hamari takaat bhi”.

To emphasise the balidaan (sacrifice), the post was accompanied with a video that showed Priyanka Gandhi addressing a rally and recalling her father’s death. In the backdrop, one can see the archival shots of Rahul Gandhi carrying the body of his father during his last journey. Priyanka Gandhi says: “Rahul got out of the car and carried the dead body of my father in the scorching heat from Trimurti. And now, the son of a shahid PM is called anti-national. Referring to the sacrifices of her family, she adds, “The democracy of the country has been built upon the sacrifices my family members have made.”

While Rahul’s recurrent evocation of the sacrifices made by his family members builds his image as a successor of a great sacrificial lineage, the Bharat Jodo Yatra made him, as he said, “a different person”.

Sporting unkempt hair and a bushy beard, as he walked hundreds of miles wearing just a T-shirt on chilly winter mornings of North India, a novel saintly image was born. Several times during the yatra, Rahul Gandhi referred to it as a ‘journey of self-discovery’. In the words of senior Congress leader Prithviraj Chavan, “It was a tapasya (penance) for him.”

The aim of the yatra was to unite the country, and from the very beginning, the message of sacrifice— sacrificing hate for love and the comfort of lives to learn and empathise—was embedded in it.

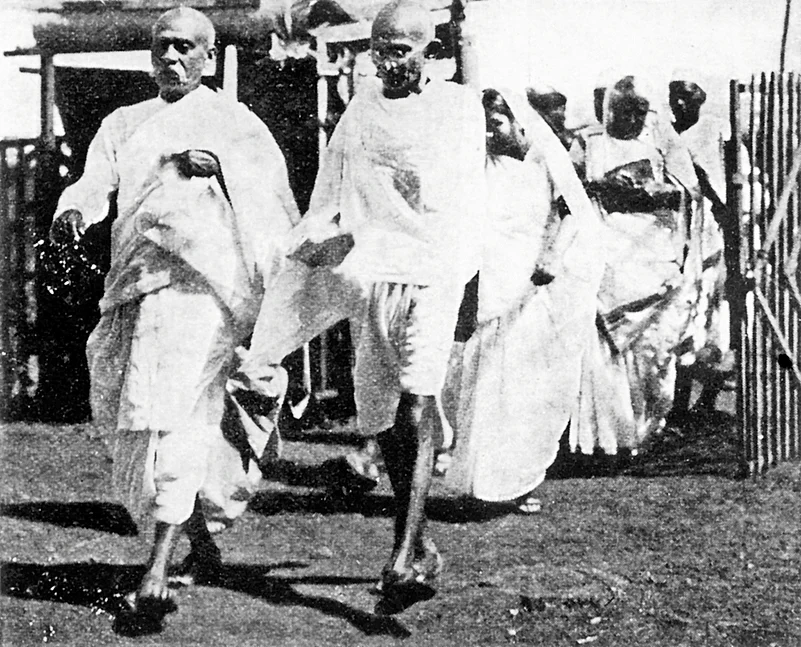

From Gandhi’s Dandi March to Swami Vivekananda’s Bharat Bhraman, the essence of sacrifice and yajna have always had revolutionary potential. In 1904, while encouraging the Indian community in South Africa to fight for their rights, Gandhi referred to ‘sacrifice’ as a way of life. Exhorting the community, he said, “We can do nothing or get nothing without paying a price for it, as it would be said in commercial parlance or, in other words, without sacrifice.”

On the potential of yajna and sacrifice, Gandhi said, “Life comes out of death. A seed must disintegrate under the earth and perish before it can grow into the grain. Harishchandra went through endless suffering to honour his word as a man of truth, Jesus put on a crown of thorns to win salvation for his people, allowed his hands and feet to be nailed and suffered agonies before he gave up the ghost. This has been the law of yajna from time immemorial. Without yajna, this earth cannot exist even for a moment.”

So, the origin of sacrificial politics in India dates back to Gandhi. According to political scientist Satish K Jha: “The concept of sacrifice is rooted in Indian traditions. Gandhi fine-tuned it and brought it into the political domain. The Mahatma and fakir have their special place in Indian consciousness—outside society, but still a part of it. They are supposed to be above material interests.” However, it is not only Modi or Rahul Gandhi, the political avatars of Jayaprakash Narayan or Vinoba Bhave also represent the politics of sacrifice.

Rahul Gandhi’s evocation of sacrifice is nevertheless different from that of Modi. While Modi banks on celibacy, “Rahul’s tyaag is of a different kind. It is based on martyrdom in family and renunciation of power,” adds Jha.

While in 2004, Sonia Gandhi didn’t take up the Prime Ministership despite leading her party to a formidable victory, in 2019, Rahul Gandhi left the post of the party president, taking responsibility for the loss in the general election. Chavan even recounts how Rahul denied taking up a ministerial post in Manmohan Singh’s cabinet in 2009. Apart from sacrificing lives, the renunciation of power has also gradually become a trademark feature of the Gandhi family.

The Bharat Jodo Yatra also added a new perspective to Rahul’s politics, feel scholars. Referring to Gandhi’s statement that “main ne Rahul Gandhi ko maar diya hai”, professor and political scientist Ajay Gudavarthy says: “This allowed the projection of a new Rahul, who is humble, with ears to the ground. Alongside sacrifice, Rahul is bringing back the images of India that works and labours hard with a sense of commitment and honesty.” Against the anti-elitist rhetoric of Modi, stand the working class/peasant images, which is not our past but the present, he adds.

While Mujibur Rehman, a political scientist and the editor of Rise of Saffron Power: Reflections on Indian Politics, accepts that Rahul Gandhi has gone through significant changes, he does not think that the sacrifices of Gandhi family members would further work in vote-bank politics. “The general feeling is that people no longer reward the Gandhis owing to their sacrifices. Had that been the case, the party would not have been reduced to such a small number in Parliament. People think the family has enjoyed a lot owing to their sacrifices and there is nothing more to offer them,” says Rehman.

However, one shouldn’t belittle the sacrifices that the Gandhi family has made, think some scholars. “The point, to my mind, is to underline that this may have been a dynasty but it has made sacrifices of the order that few families have in the BJP. That at least seems to me to be the unstated part of this evocation,” says political scientist Aditya Nigam.

He does not think that the ‘sacrifice trope’ works for Rahul. “In fact, he doesn’t even wear the kurta pyjama—leave alone the khadi that Gandhian and Congress leaders of yore (but many even today) wear,” says Nigam. Instead, the “discourse of ‘sacrifice’ has been Modi’s card for the longest time. He abandoned his wife because as everyone can see, he cannot take any responsibility for anything. He did not sacrifice conjugal life for the country or anything like that,” he adds.

As Rahul Gandhi wraps up his recent two-day stay at the Golden Temple indulging in ‘sewa’—achieving the feat of being the only non-Sikh politician to do so—his newly-found avatar takes a much deeper spiritual turn.

The uncanny similarity between his recent column in a national newspaper and Mahatma Gandhi’s spiritual aspiration makes one further think through the new ideals of the leader. While the call for ‘sacrifice’ remains an unsaid virtue, Rahul writes, “This action and duty to defend others, especially the weak, is what a Hindu calls her Dharma. Listening for and acting on behalf of the world’s invisible worries through the prisms of truth and non-violence.”

(This appeared in the print as 'Politics of Sacrifice')