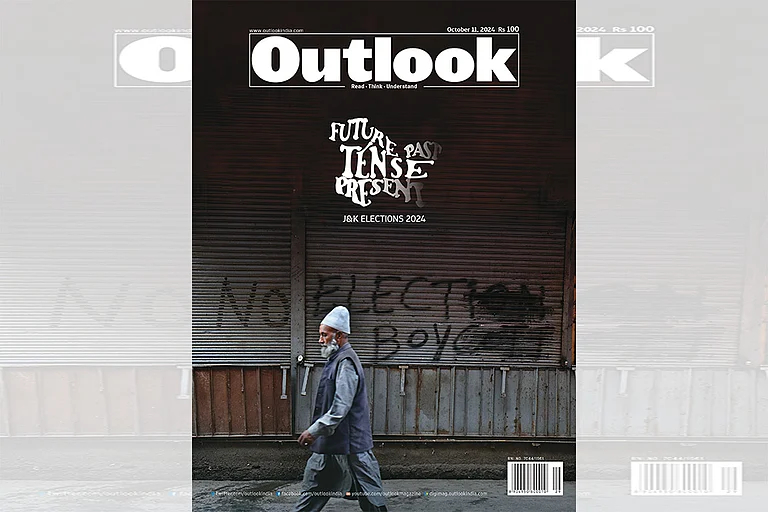

This story was published as part of Outlook Magazine's 'Future Tense' issue, dated October 11, 2024. To read more stories from the Issue, click here.

The day was September 29, 1944. The annual session of the National Conference (NC) at Srinagar was bustling with fresh energy. The fight against the ruling Dogra dynasty had reached its peak. Sheikh Abdullah, popularly known as Sher-e-Kashmir, declared a new beginning—the promise of a ‘Naya Kashmir’. Carefully choosing his words, Abdullah said, “The NC fights for the poor, against those who exploit them; for the toiling people of our beautiful homeland against the heartless ranks of the socially privileged...

Cut to 2024.

Much water has flowed along the Jhelum’s banks over the past eight decades. But the promises made by Abdullah, now represented by the Sher-e-Kashmir’s son Farooq and grandson Omar, remain constant, albeit in a different spatiotemporal context. This time, the NC’s election manifesto for the ongoing assembly polls pledges yet another ‘Naya Kashmir’. One, that would undo the ‘injustices’ meted out to the land and its people over the years.

The NC, however, is no longer the only articulator of a ‘Naya Kashmir’.

In 2023, after the Supreme Court upheld the abrogation of Article 370, Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed his hope for a ‘‘brighter future’’ that is about to shape ‘Naya Jammu and Kashmir’. As the union territory goes to polls after ten years, contesting NC and BJP narratives over the ingredients of a ‘Naya Kashmir’, coupled with promises of ‘‘development’” made by the major political parties in the fray, captures the shift in the politics of the erstwhile state.

While the early days of Sheikh Abdullah, till his arrests in 1953, heralded a time of economic reforms, the politics of the 1970s to the days of militancy in 1987, was centred on the question of the restitution of the autonomy. The post-militancy phase marked the bridging of the separatist and mainstream narratives coupled with the emergence of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) as one of the main regional forces.

These battles of narratives were followed by two major transitions, the PDP’s unanticipated bonhomie with the Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) and the abrogation of Article 370, which changed the politics of the Valley forever.

Politics of Autonomy

In the first assembly election after the abrogation, regional parties expectedly invoked the restoration of Article 370 as an important poll plank. Claiming credit for including the critical element of special status in the Constitution, the NC has pledged to restore both Article 370 and 35A of the Constitution, which bestow ‘‘special status’’ and domicile rights to native Kashmiris. The idea of ‘‘political autonomy’’, however, remains at the core of its electoral promises. The first pledge in the party’s poll manifesto reads: “(We will) strive for the full implementation of the Autonomy Resolution passed by the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly in 2000.”

In Sheikh Abdullah’s reign, the original framework for autonomy for J&K included a separate flag and constitution for the state. However, it was never fully implemented. With the 1975 Delhi Accord leading to Abdullah’s return to Kashmir politics, the claim gradually lost relevance.

A former professor at the University of Jammu and a scholar of Kashmir politics, Rekha Chowdhary says, “In 1975, the Government of India clearly said to Sheikh Abdullah that the clock cannot be turned back. So, the proposition of ‘autonomy’ is more a political rhetoric than one having any concrete foundations.” Referring to the NC’s claims of the restoration of Article 370, Chowdhary adds, “Even Farooq Abdullah states that it might take a hundred years to restore the pre-2019 situation. Talk about restoration of autonomy is rhetoric only, it is for the political consumption of the voters.”

As militancy and separatism took over Kashmir’s politics, forcing the NC into ‘political hibernation’, the claim for autonomy gathered more dust, until it was reiterated just ahead of the 1996 elections, when the NC’s political resolution said: “The time has come when this state of affairs should be reviewed in order to restore autonomy to its pristine and original form.”

After a decisive win in the 1996 elections, the NC government, led by Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah, formed a committee to review the status of autonomy accorded to the northern state, as part of its promise to voters.

After three years, the committee’s report concluded that “serious deviations were made and vital positions were altered in the state’s constitutional relationship with the centre by repeated application of constitutional orders, with the result that Article 370 was ‘emptied of its substantive content’.”

Resolutions reiterating autonomy passed by the state assembly were outright rejected by the then National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government at the Centre. Despite this, the NC continued to align itself with the power structure at the Centre, first supporting the Union Front in 1996 and then joining its rival alliance, the NDA, in 1999. In the Union Front government, the party MP Saif Uddin Soz even got a ministerial berth.

In 1998, during the no-confidence motion against the Vajpayee government, Soz went against the party whip and voted against the government, leading to its untimely fall. But that didn’t stop the NC from continuing to mingle with the BJP. Omar Abdullah went on to become the external affairs minister during the NDA-I government. Abdullah’s silence during the Gujarat pogrom and the implementation of the POTA Act, which allegedly had severe consequences for Kashmiris already suffering under the PSA, did not sit well with voters. It was only after NC’s setback in the state assembly polls in 2002, that Abdullah resigned from the ministry.

Politics of Dignity and Conflict Resolution

The question of “dignity of Kashmiris”—a phrase that appears five times in the current manifesto including the title—doesn’t quite match the NC’s political history. Now, Omar Abdullah in his address in the manifesto, refers to the document “as a testament to our shared journey, a roadmap to reclaim the dignity and honour that has been the cornerstone of our identity for generations.” The statement comes with the promise of repealing the PSA, the release of all political prisoners and rehabilitation of Kashmiri Pandits, echoing NC’s politics in the post-2002 elections when it failed to form the government.

Since 1989, mainstream Kashmiri politics has struggled with legitimacy amid rising separatist sentiments. In 2002, the PDP, with Congress’s support, broke NC’s dominance by introducing a more “mainstream” version of “self-rule” and political pluralism. Founder Mufti Mohammad Sayeed advocated for a regional council with members from both Kashmir and Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK), safe passage for militants, cross-border trade with dual currencies and the revocation of AFSPA, bringing separatist narratives into mainstream politics. In 2002, the PDP formed a government with Congress’s support, marking a phase where mainstream parties adopted a softer separatist tone.

The PDP’s “soft separatism” influenced the NC too, pushing it to address military excesses and human rights violations during militancy, issues it had previously avoided. Both parties recalibrated their positions, with the NC also echoing separatist narratives. NC’s Mehboob Beg in 2008 urged India and Pakistan to involve Kashmiris in resolving the dispute, while another senior leader Abdul Rahim Rather spotlighted the “vexed” Kashmir issue. Omar Abdullah even called for a Truth and Reconciliation Commission led by a neutral country.

The NC continues to rely on human rights and constitutionalism in its electoral strategy, while the PDP, weakened by its misadventure with the BJP, is back to banking on the party’s ties with former separatists.

Syed Saleem Geelani, former chief of the National People’s Party, who recently joined the PDP, described the party as a “natural fit” due to its advocacy for democratic, human and political rights in Kashmir. Although Geelani isn’t contesting this time, the PDP has fielded religious leaders with separatist links, including Aga Muntazir Mehdi, a Shia cleric and the son of a former Hurriyat leader.

In the lead-up to the elections, the PDP insisted that it isn’t contesting for mere seats, but for a “political solution” for Kashmir. While its current manifesto references Article 370, PDP chief Mehbooba Mufti clarified that the focus isn’t solely on restoring Article 370. “The issue in Kashmir is a political issue requiring a political solution,” she stated.

Politics of Development

Beyond regional dignity and autonomy, development has become central in both national and regional party manifestos in Kashmir.

While the BJP leads the development narrative, both PDP and NC underscore development in their respective manifestos. NC has promised 100,000 jobs, a Youth Employment Act, 200 free units of electricity, Rs 5,000 per month to female heads in Economically Weaker Section (EWS) families, free LPG cylinders and free education up to university level.

Elucidating on the transformation in the NC’s politics, Chowdhary says, “Gone are those days when the NC centred its political discourse on autonomy following its political hibernation in the 1990s due to the compulsion of separatist politics. Now the party’s politics is much more pragmatic. They are focusing on governance from an economic aspect. They are also much more flexible now.” In 2021, the NC accepted the PM’s invitation for meeting in Delhi. The party also appeared before the delimitation commission despite initial denial. The party changed its stance regarding fighting elections, she adds.

NC ally Congress is also focusing on development. In its manifesto, the Congress has promised preference to domiciled J&K residents in “jobs, government contracts, land allocation and natural resource concessions”. It has also promised Rs 3,500 per month to ‘‘unemployed qualified youths’’ for a year.

AICC media coordinator of J&K, Abbas Hafiz Khan, says, “We are not going to shift our focus from statehood. We went to the people of the Valley and they helped build our manifesto. The NC is a different party with a different agenda, but we aim to form the government and run it based on a common minimum programme.”

Khan also says the Congress will advocate for the land rights and employment opportunities of Kashmiris. “In line with Bihar and Andhra Pradesh, we will request a special package from the Centre to address these issues,” he adds.

Incidentally, the BJP has also promised restoration of statehood in their rallies, though the party’s manifesto makes no mention of it. At his Jammu rally, Modi said that only the BJP can restore the statehood of J&K. An irate Khan says that such promises are nothing but a jumla. “If the BJP wanted to restore statehood, why didn’t they do it in the last five years?” he said.

The Age of ‘Vikas’

Since the abrogation of Article 370, a new political landscape has taken shape in J&K, marking a shift in strategies and narratives across the region.

“After years of struggle and sacrifices for ‘Ek Vidhan, Ek Nishaan, Ek Pradhan’ we have fully integrated Jammu and Kashmir with the rest of India,” the BJP’s 2024 assembly elections manifesto proudly proclaims, painting a zaffran (saffron)-tinted picture of development and ‘Badalta Kashmir’ post abrogation of Article 370.

The narrative is a vindication of the 1953 slogan coined by Jan Sangh founder Shyama Prasad Mookerjee: “Ek desh mein do vidhan, do nishan, aur do pradhan, nahin chalenge, nahin chalenge” (Two Constitutions, two flags and two heads of state are unacceptable within one nation). At a recent rally in Jammu, Narendra Modi claimed that Kashmiris are finally “breathing freely” and welcomed the “festival of democracy”, while lauding ‘Badalta Kashmir’.

Modi’s penchant for “undoing the asymmetric annexation of Kashmir with India” is not new, as social scientist Bharat Bhushan notes in a 2020 paper titled Overhauling Kashmir Politics: Incubation of Artificial Political Processes Destined To Fail. Kashmir has been an important agenda in his electoral pitches across the country in the past decade and one that tends to fire the national imagination.

Modi has previously claimed how he marched from Kanyakumari to Srinagar and unfurled the tricolour at Lal Chowk on January 26, 1992, when “militants were wiping their shoes with the Indian flag and stomping on it,” invoking the imagery of an inveterate Indian braving the guns of militants to hoist the national flag.

In his paper, Bhushan puts into context the Tiranga Yatra, which was launched and led by the then BJP President, Murali Manohar Joshi, with Modi serving as the convenor of the event at that time. Lal Chowk, writes Bhushan, “had been vacated and put under curfew. As they struggled to raise the flag, the flagpole snapped into two, hitting Joshi’s forehead. Finally, Joshi hoisted another flag provided by the state administration with just 67 BJP workers in attendance to slogans of Vande Mataram.” No Kashmiri was present to witness the event.

The incident seems to foreshadow the party’s current rhetoric around Kashmir’s “integration” and “development”. In its manifesto, the BJP offers glimpses of the “progress” it claims to have brought to J&K through initiatives such as the Zojila tunnel project, setting up of IIT, IIM and AIIMS and hosting events like Formula 4 racing and the Srinagar Marathon.

It highlights the “transformation” of Kashmir from the “Capital of Terrorism” to the “Capital of Tourism”, with a record 2.11 crore tourists visiting in 2023. The manifesto also mentions Rs 80,000 crore worth of investment projects since the abrogation of Article 370.

Locals in Srinagar assert that many of these proclamations aim to impress voters in New Delhi rather than those in J&K. The manifesto emphasises development and investments, with “Viksit Kashmir” (developed Kashmir) as its core agenda, aiming to end separatism and terrorism. However, the party’s success depends on consolidating the Hindu vote in Jammu and splitting Kashmiri votes in the Valley, where independent candidates could play a crucial role, observers claim.

“The manifestos are mainly for the BJP’s New Delhi audience. In the Valley, Kashmiris do not vote for development; they vote based on identity and emotion,” says veteran Srinagar-based journalist Sayeed Mallik, adding, “This time, the emotion is distinctly anti-BJP, mainly for what it did on August 5, 2019. There is a sentiment to avenge the suppression, oppression and humiliation faced by the people in the last five years.”

The BJP has been criticising its rivals, the NC and former ally PDP, for exploiting the emotions of Kashmiris in their quest for power. “Despite their claims of unity, these parties frequently betray one another yet compromise for power, once again seeking to exploit the people of Jammu and Kashmir,” its manifesto states, taking potshots at the regional parties, while ignoring its own past alliance with the PDP.

In 2015, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed called the BJP-PDP partnership the “coming together of the North and South Pole,” while Mehbooba Mufti later described it as a “cup of poison” after the alliance crumbled in 2018. Bhushan notes that the BJP’s plan to eliminate regional parties involved invoking corruption charges against their leaders. When Mufti sought to form an alliance with the NC and the Congress to save her government, the BJP-appointed Governor, Satya Pal Malik, dissolved the legislative assembly immediately after the BJP’s withdrawal.

Observers also point out to the role of the BJP in creating new ‘proxy’ leaders, such as former civil servant Shah Faesal, who quit the Indian Administrative Service and founded the Jammu and Kashmir People’s Movement in 2019, only to be conveniently reinstated in service by the Modi government in 2022.

From Separatism to Elections

Another notable aspect of the elections in the Union Territories of Jammu and Kashmir this year is the entry of separatists, fielded by parties like the PDP or backed by banned separatist organisations such as the Jamaat-e-Islami. Many of these candidates, some with Hurriyat links, aim to capitalise on the “sentimental vote” by appealing to Kashmiri identity, while also throwing in promises of “development”.

Jamaat’s Pulwama candidate, Dr Talat Majid, for instance, is campaigning on the slogan of Development with Dignity, making key promises like “safeguarding Kashmiri identity,” ensuring “police accountability,” stopping the “misuse of the PSA,” and putting an end to “preventive detention before VIP events,” among other commitments.

The BJP shifted from a political to an apolitical approach in J&K, focusing on development and governance.

The recent Lok Sabha win of Engineer Rashid from Baramulla, defeating prominent opponents like Omar Abdullah and Sajad Lone, while in prison, marked a turning point for separatists. Rashid, historically opposed to the Congress, the NC and the PDP, is seen by critics as a BJP proxy in the electoral mix.

Rashid’s popularity has elevated him and other separatist voices to potential ‘kingmakers’. While mainstream parties welcome separatist leaders as a democratic win, many suspect BJP manipulation. “Appeal for separatist politics is invisible. But deep down, its lurking appeal is palpable. Voters, however, need to be wary of proxies,” warns Mallik, citing emotional and religious connections separatists hold.

In Jammu, Hindu-majority residents are concerned about the BJP’s alleged ties to separatists amid a rise in militancy since the abrogation of Article 370. With 43 attacks in 2023 and 20 in 2024, including a deadly attack on Hindu pilgrims in Reasi, fears have grown, especially among Kashmiri Pandits seeking relocation for safety. Activist Sanjay Tickoo has filed petitions in court, citing the Centre’s failure to protect religious minorities. Meanwhile, the BJP’s campaign has banked on Article 370 and appealing to Hindu sentiments in Jammu.

“They have been talking about building temples and about Article 370. Nothing about jobs, the impact of abolishing the Durbar system or education and safety. These are the things that matter to voters,” a Jammu resident said over the phone.

With the BJP confident of securing a majority in Jammu and the NC looking at gains in the Valley, speculation over potential alliances has begun circulating among political analysts. However, an alliance seems off the table for the top two regional parties in the Valley, as both the NC and the PDP have rejected the idea.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Mallik asserts that the PDP’s poor performance in the Lok Sabha elections earlier this year was evidence of the public’s anger toward the party for allying with the BJP. “People have not forgotten or forgiven,” he says. The NC also remains wary of any potential tie-ups that may cause embarrassment in the long run. “After all, they can see what happened to the PDP,” Chowdhary quips.

(This appeared in the print as 'Promises to Keep')