Abdul Ahmad Mir occasionally opens a window of his double-storey house to catch a glimpse of the daytime disorder down the road in the schoolteacher’s south Kashmir village. It is, again, youngsters throwing stones at the security forces—with a vigour that adds to the prevalent tension, which reminds the middle-aged man of 1990 when the Valley experienced its first bout of insurgency.

Mir, 56, has vivid memories of that army crackdown in his native Turkwangam more than a quarter century ago when the Border Security Force cordoned off the village. “We were terrified. Most of us residents ran away; I too escaped,” he trails off. “I returned home after eight days.” In subsequent crackdowns that winter, the villagers were made to assemble at an open field in the locality and forced to sit over snow. “We were frisked and questioned. We would obey every order to the fullest. Silently. Like cattle,” the medium-build man with a white beard says, managing to smile.

An elderly person joins in and nods in agreement to his friend’s recollection. “Yes, there was extreme fear,” says Abdul Rashid, who works in a nearby apple orchard he owns. “We were a terrified generation.” By the turn of the century, the situation bettered and no crackdown had been carried out in Turkwangam for a good 17 years.

All that has altered now. Unrest rules the picturesque region this summer around Shopian, where the young crop is least amused to hear the way Mir’s generation used to react to search operations. On May 4, the army, backed by the Jammu and Kashmir Police and paramilitary CRPF, launched a major operation to trace militants in Turkwangam and 19 adjacent hamlets. The ground reaction has been in sync with the disturbing vibes the security forces get during similar exercise in the countryside of south Kashmir.

In fact, this is the army’s biggest crackdown on these 20 villages. The operations have by far failed to better the situation, as militants continue to be on the offensive. Particularly targeted are the police, which have lost half-a-dozen cops in the past one week in separate militant attacks in south Kashmir. Students across the Valley continue to protest by throwing stones and bricks at the police and the paramilitary.

Suddenly, there is a complete halt in the activities of pro-India political parties. Almost all their workers have migrated to Srinagar. The ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP) too has disappeared from its bastion of south Kashmir, while the only way the National Conference (NC) has found to hold its fort is by making sustained noise on social media. Chief minister Mehbooba Mufti is candid enough to compare the present situation with that of the grim 1990s. “I remember 1996, when it was difficult to even conduct a public meeting,” she says during a customary press briefing at the opening of the civil secretariat in Srinagar on May 8. “But people have come out of it. They will pass through the present crisis with resilience.” Ex-CM Omar Abdullah of the chief opposition party regularly tweets against the PDP and its ‘inept handling’ of the situation. That apart, the NC too has not held any public meeting in the region in the recent past.

In Turkwangam, one can sense a loss of people’s faith in pro-India regional parties. Mir and Rashid, unlike in 1990, haven’t fled the village. Instead, they view from their big concrete houses the pitched battles between the youths and the army. “The youngsters haven’t so far allowed the army to search anyone’s house,” Mir says. “They aren’t afraid of anybody, you know.”

As Mir continues the conversation at the local market, more youths of the village come in. The men are in their 20s. Some of them, strikingly, are draped in pherans—the long Kashmiri cloak used in winters. The elder among them introduces himself as a spokesman of the group. A tall and well-built man, who says he left studies for apple business. “I wasn’t in my village when I heard about the operation,” he reveals. “I rushed back and joined fellow youths in picking and throwing stones.”

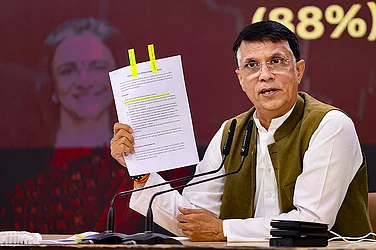

Security forces at a search operation in Shopian on May 4

Turkwangam, 16 km from the Shopian town, has been a prosperous village with houses either two- or three-storeyed. Shopian, which is 60 km northwest of Srinagar, is a district known for its apples. On both the sides of Shopian-Turkwangam road are vast orchards growing the red, sweet fruit. Most of the villagers deal with this horticulture that has enabled them to buy and drive brand-new cars. On the fences of the fields along the road are seen slogans such as ‘Long live Burhan Wani’ in memory of the young militant who died in an encounter with security forces in last July. Also visible are paintings of green Pakistani flags.

In 2014, villagers in Turkwangam voted for the PDP. Today, inversely, they say the days of pro-India parties are over. “Mind you, there is only one solution to Kashmir—and that is with the gun,” says the ‘spokesman’ at the gathering. Others agree. They say several youths want to join the insurgency, but the militants are refusing to recruit them.

“You are asking why I came back to throw stones?” asks the ‘spokesman’ in apparent combativeness. “Several people were killed last year (in the post-Wani clashes between civilians and forces). Many were blinded, injured. Today, if I fear that I will get killed by bullet or pellet, I wouldn’t have hurled stones. I don’t fear anyone.” Another youth scoffs at reports that Pakistan pays the men for the stone throwing. “How come!” he argues. “Pakistan is economically weaker than India. So, why don’t they (India) pay us more to get this stopped? Our struggle has nothing to do with money.” The youths have downloaded VPN proxy services to reroute internet traffic, so as to counter a state government ban on social media.

In Kuchedoora village alongside the Kulgam-Shopian road, a family is mourning. Having lost a member in the ongoing turbulence, they have erected a tent outside the house, where people are streaming in to meet the head, Abdul Hakim Sheikh, and express condolences. On the evening of May 5, Sheikh’s younger brother Nazir Ahmad was killed when the militants fired at the army at Imam Sahab hamlet. The army vehicle, which Nazir was driving, was returning from the villages after a search operation, when they came under attack, wounding two soldiers and killing the young man—a father of two. The police see the attack as militants’ attempt to spread the public impression of the insurgents being in a “commanding position” in south Kashmir.

Nazir’s family is angry with the army. “They took away my brother to ferry soldiers for the operation,” Sheikh says. The men at the army camp of 62 RR at Choudhary Gund seized Nazir’s driving papers before taking him to the operation site, Sheikh claims. “The army would often force Nazir and other sumo drivers to transport them for night patrolling. They wouldn’t provide anything for the services.”

This month has seen a surge in militant attacks. On May 1, ultras attacked a Jammu and Kashmir Bank van in Kulgam and killed five policemen besides two guards of the semi-government financial institution. A day later, militants looted two branches of the bank in Pulwama, forcing authorities to stop cash transaction in its 40 branches in Pulwama and Shopian. Militant outfit Lashkar-e-Toiba later sought to distance itself from the heist.

On May 6, the militants attacked a police party in Kulgam, killing a cop and three civilians. The shootout also claimed the life of a militant, Fayaz Ahmad alias Setha, who was involved in a 2015 attack on a BSF convoy in Udhampur and was on the ‘wanted’ list of the National Investigating Agency. A day after Fayaz’s funeral, a group of five militants gave him gun salutes. On May 9, militants kidnapped a young army officer, Ummer Fayaz. The 22-year-old was abducted from his maternal uncle’s house in Shopian in the evening. A lieutenant in the Indian Army, the native of Kulgam had gone to Shopian to attend his cousin’s marriage in Harmain. The next morning, his body was found at the chowk of the village.

A senior police official says the larger chain of developments indicates the end of a middle ground in the Valley. “The message is no pro-India has a place here,” he tells Outlook. “It is like either you are with us or against us. True, militancy has remained alive in Kashmir; it’s always seen part of a separatist political movement. But, it has to be seen now how people in the next few months react to such killings. That will determine the fate of the insurgency.”

A series of videos has been released over the past few weeks, showing a section of militants rejecting the struggles and trashing the waving of Pakistan flags—thus hinting at a new militant ideology bearing pan-Islamic overtures. This has angered separatist leaders Syed Ali Shah Geelani, Mirwaiz Umar Farooq and Yasin Malik, who reject the line. To them, the “freedom struggle” of Kashmiris is exclusively a local movement, with the “first and last goal” of ending India’s “forcible occupation of the region”. It has “nothing to do with global Islamist movements”.

Army sources say the present situation in Kashmir cannot be compared with that of the 1990s. “Today, the number of militants is between 200 and 250—a fraction of what it was 25 years ago,” a defence official says. “Also, this time, we have strong fencing along the LoC and an anti-infiltration grid that is in place. The present turmoil is just a continuing reaction to the Wani killing.” However, police say the number of militants can swell if weapons are made available to them.

In Srinagar, Kashmir Police chief Syed Javaid Mujtaba Gillani calls the fresh militant offensive a psychological warfare. On May 8, at the opening of the darbar, the usually-reticent officer flayed militants and their uploading of videos on social networking sites. “We will defeat their motives. We are blocking the portals and networking sites,” Gillani said. According to him, Kashmir has around 200 militants of whom 110 are locals. “Thus, for the first time in past one decade, local militants outnumber foreigners, as 95 joined the militancy since last year,” the officer says. This is contrary to the perception that the whole of south Kashmir is problematic, he adds. “Only a few pockets in south Kashmir give challenge to the forces.”

The CM insists on dialogue. “Even the earlier two-decade-long turmoil ended through a series of negotiations,” Mehbooba points out. NC president Farooq Abdullah, who would deride the CM for not getting anything from the prime minister, met Narendra Modi on May 9 and urged him to start talks. All eyes are now on the Centre.

By Naseer Ganai in Turkwangam, Shopian