Prof G.N. Saibaba passed away at the age of 57 on October 12, 2024. Here, we present an article that Prof. Saibaba wrote for the Outlook Independence Day Special issue of 2024, recollecting his years in jail as a political prisoner.

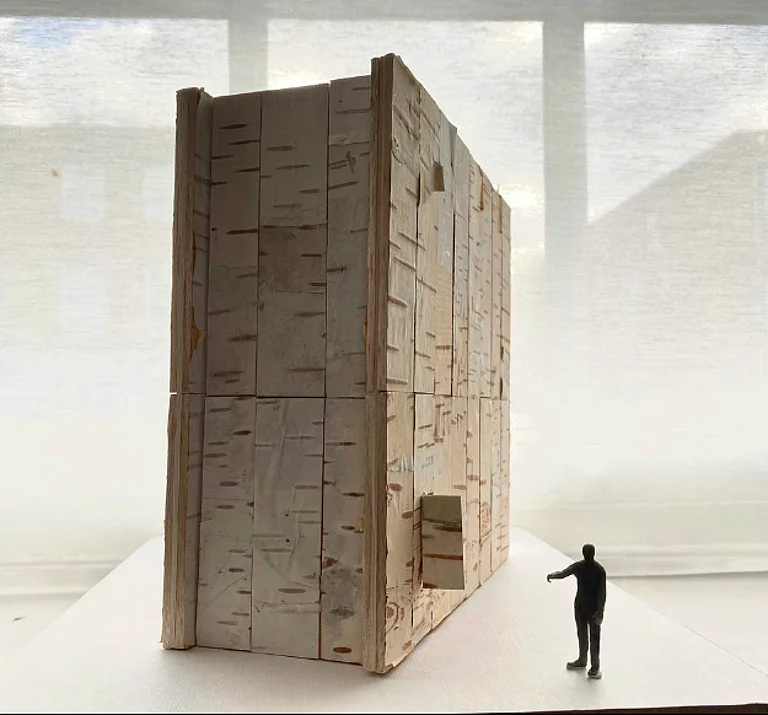

Out of ten years under the draconian jaws of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), I was in a prison within a prison called Anda Cell of Nagpur Central Prison for more than eight-and-half years. That made me taste another kind of unfreedom—slavery, bonded labour, brutality and the anti-human nature of the state.

Freedom for a few is no freedom. This has been my understanding since my school days.

Human nature ordains that one cannot live without freedom. I wonder how other beings perceive unfreedom; we know that indeed animals loathe fenced enclosures, birds hate cages and domesticated pets scorn the air-conditioned heavens. I do know that we humans have a colourful way of imaging the freedom we seek for ourselves, carried from aeons ago, beyond the Magna Carta (1215) that curtailed arbitrary ruling power to say ‘rule of law’ and ‘equality for all’.

But, as always, the pertinent question still looms large in India: Can there be freedom where caste works as the basic principle of governing a society? And social fascism that is the foundation of our social structure. Here, a thousand constitutions enshrining all the best rights in the known human society can never work.

Freedom, liberty and fraternity remain the ideals of Western democracy that never attracted the imagination of our caste-divided society. We have been accustomed to living in a prison-house of castes—oppressor and oppressed imprisoned in the same house for centuries.

The notion that no person or circumstance can control my freedom of mind has remained a dearly liberating idea since my schooldays.

My 90 per cent disability due to polio in childhood was no obstruction for my free thinking. But for the first time, this very disability became a weighty tool in the hands of the rulers and their authorities to control my body and mind once I was imprisoned. They exercised their power over my free thinking by weaponing my disability. For the first time in my life, I began to feel that I was a disabled person.

First, they asked why I should face the wrath of governments through my campaigns for the rights of the people when I couldn’t even stand or walk. If I agreed to stop all my activities for these liberties, there would be no case against me. They warned me, ‘You are such a disabled person you can’t face the consequences; it is for you to decide’. The threat was powerfully tangible. But my will to freedom was stronger.

I knew if I didn’t budge to their evil advice, I probably wouldn’t survive. But I was fully drunk with the notions of freedom since my childhood. At that moment there were only two options before me. One was to lose my freedom, and the other life. I preferred the second.

There was no accessibility in the ‘Anda Prison Cell’ for me to reach the toilet seat or bathing area or to fetch a glass of water for myself. Two people had to lift me in their hands physically every time.

Three decades after the first law was made for the disabled persons, the governments remained the main violators of it. No accessibility was there to go and attend mulaqat (prison interviews with family members and lawyers), or to go to prison hospital or to meet any of the prison officials in their offices.

Again, helpers need to lift me. There is no concept of human dignity anywhere on the horizon. The prison sustained in its nineteenth century existence as was built by the colonial rulers now with only some cosmetic changes like CCTV cameras and online mulaqats in inaccessible places.

In a society of walls within walls everywhere, one can hardly resent prison walls and where no accessibility is the norm for most of the oppressed people, one can least expect wheelchair-accessibility in a prison. I expressed myself in 2019 from my tiny prison cell in a letter to a child:

The Carceral Walls

The walls are thick, hard and high

with hidden iron rods inside

like the deathly spokes of castes.

They thrive from the roof above

and the foundation below.

They aren’t the only four around me

but walls within walls

in concentric circles

like the castes within castes

prison-housing my country,

or the spools of concertina wires

incarcerating a valley of love.

Bricks and mortar,

stones and iron

aren’t their make alone.

They stand on the invisible

pillars of brutal power.

They lick my caged time dry

and block the world of dreams

from my vision’s ambitious gaze.

The walls breed walls of hate.

They don’t collapse

on their own weight.

(written on February 10, 2019)

August 15 or January 26 are two dreaded dates in the prison for every inmate. In order that the prison officers celebrate these days, all barracks and cells of the prison are locked up very early in the day leading to 18 to 20 hours of lockup period on those days. You don’t know how to drag the days of lockdowns within lockups.

On such gloomy days of long lockups, I re-read Babasaheb Ambedkar in my prison cell. I recalled all his writings as much as possible. Babasaheb famously gave a clarion call to all those who were oppressed and suppressed for millennia which I never forgot for a single day while being in the prison as well:

“Freedom of mind is the real freedom.

A person whose mind is not free though he may not be in chains, is a slave, not a free man.

One whose mind is not free, though he may not be in prison, is a prisoner and not a free man.

One whose mind is not free though alive, is no better than dead.

Freedom of mind is the proof of one’s existence.”

I was chained, put in a prison and they made me almost dead, only thing that survived was my freedom of mind and then declared to myself ‘I refuse to die’. That is the kind of freedom in the land of no freedom.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

G N Saibaba is a scholar, writer and human rights activist

(This appeared in the print as 'Anda Prison Cell')