Even on the last Sunday before Goa elects a new legislature on March 3, the sprawling river island of Divar is unhurried and calm, just as the locals have always liked it.

Divar comprises three ancient villages, spread out over two low hills that dominate the island landscape directly across from the centuries-old port city that once served as capital of the Estado da India.

Visible for miles around is the church of Nossa Senhora de Piedade, widely considered a masterpiece of the Indian baroque style of architecture that flowered in Goa in the 18th and 19th centuries. It is built directly on the ruins (some of which are still visible in the adjoining cemetery) of an important temple dedicated to an image of Saptakoteshwar that drew pilgrims from across the region before it was destroyed by the invading Bahmani sultans of Bijapur, whose intolerance for Hinduism was perpetuated by the Portuguese for further centuries until their Estado da India was defeated and annexed by Nehru in 1961.

In the first couple of centuries of Portuguese rule, while their capital city (now called Old Goa) flourished into the richest trading post the world had ever seen, and travellers and traders from across the known world thronged the territory, Divar also thrived as the countryside retreat of wealthy noblemen and adventurers, the fidalgos who made their fortunes in the globalised bazaars across the river.

But by the 18th century, the Portuguese ability to project its power into Asia had dwindled to approximately zero, and Old Goa effectively crumbled into jungle.

Ambitious native traders and administrators seized an opportunity to move the capital downriver to the point where the Mandovi met the Arabian Sea opposite the Aguada and Reis Magos fortresses. Panjim supplanted Old Goa, and the old capital now lapsed into disuse for centuries, its few surviving religious buildings now soaring over acres of coconut palms that sprouted where once were buildings and marketplaces.

Divar also slumbered. The island is extremely close to several centres of 20th and 21st century growth and development, but the locals seem to have arrived at a consensus to keep most of it at bay. All the other islands that are significant parts of the Cumbharjua constituency— Akhada, Santo Estevao, Cumbharjua—are connected by road bridges to the mainland.

But the natives here are different. Most Divarkars are bitterly opposed to a bridge, fearing that real estate speculation will wind up depriving locals of access to their own land as is now common all across Goa, and a flood of migrants will overrun the island’s culture and society with irrevocable effects. In talking to locals here, I was struck by several references to the island “holding out” like Asterix’s rebellious village in Roman-occupied Gaul.

It’s an idea and ethic taken seriously here, which is precisely why the incumbent, Pandurang Madkaikar and his ostensible “main opponent” Nirmala Sawant, are already focusing cash, inducements and other resources into the island.

Divar houses almost 25% of the Cumbharjua electorate, almost 5000 voters divided evenly between Christians and Hindus, and its usually compliant Congress voters are showing signs of defecting in large numbers to the unique, feel-good campaign being run by the maverick priest, Bismarque Dias

While waiting for the Dias’s final “Kindness Picnic” of the 2012 electoral campaign, I wander over to one of Divar’s most prominent citizen’s house for tea. Retired from a multinational company to his ancestral property, he’s full of local intrigue, and tells me that Madkaikar’s men are seriously worried that they are going to lose their stranglehold on power. “If it were not for this priest,” he declares, “Sawant would be a sure shot,” recalling that Congress bigwigs rushed to the island on the very last night before the 2007 polls in a last-ditch attempt to buy support.

That intervention narrowly succeeded in delivering the seat to Madkaikar. He defeated Sawant by just 500 votes out of the more than 20,000 cast. But this year, it isn’t just him who’s nervous after surveying the restive, anxious electorate, it’s Sawant as well. All the cozy certainties of past politics in the islands are gone in 2012, swept away by the stubbornly persistent Bismarque and his seemingly indefatigable crew of volunteers.

Thus, except for the priest— who clearly thinks he’s going to win— everyone else on Divar on the last Sunday before the 2012 polls is completely at sea about what their political future holds. That prominent retiree even tells me “this is a new kind of politics for Goa. Even if Bismarque loses here, he has planted the seeds for the kind of real change I never thought possible in my lifetime.”

As the sun’s afternoon rays mellow towards the horizon, I make my way out to the spot that Bismarque’s campaign team has selected for its final “Kindness Picnic.”

It’s stunningly beautiful, like much of the rest of this blessed island: we gather under a huge old mango tree that has served as a way station for generations, with mangrove-fringed backwaters shimmering gold to one side, and a magnificent sweep of paddy fields on the other.

In the near distance, glowing warm in the fading light, the surreal sight of outsized churches and convents looming high above a blanket of coconut fronds: the largest church in Asia, the largest convent in Asia, the Basilica, the Cathedral.

Just a decade ago, this unique (UNESCO-protected) collection of landmark religious architecture dominated its hillside opposite Divar. But the view from the Kindness Picnic in 2012 reveals a different picture— there is now massive real estate development encroaching on the unique (UNESCO-protected) heritage district on all sides, including from the plateau above. It is as though vast complexes of villas were housed on the lawns around Humayun’s Tomb in Delhi, like a shopping mall being erected in the courtyards of the Golden Temple.

Every single Divarkar I spoke to about the rampant, visibly inappropriate real estate development taking place in Old Goa expressed anger to the point of shouting, and waving fists.

In their view, the government of India has abdicated its responsibility, leaving the tiny district of Cumbharjua powerless in the face of the ambitions of its political class and newly minted economic elites.

But what is even worse was the widespread belief that nothing is going to change, that the destruction of Goa is inevitable. More than once I was told, “My kids are already out of Goa, there is no future for us here”. People repeatedly reminded me that many sources indicate that Goa is already majority-migrant, that the future is likely to bring an entirely different kind of politics that becomes increasingly insensitive to local concerns.

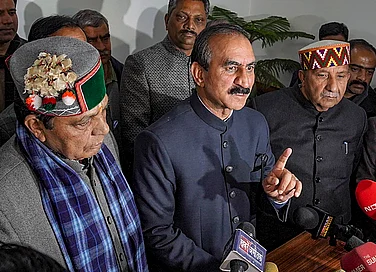

Photo: Vivek Menezes

Given all the pessimism and resignation washing neck-deep over the island, it’s quite a startling thing to see Bismarque treading purposefully towards the last Kindness Picnic in his worn rubber chappals, wide smile still cleaving his face.

Even as everyone else is fading after a long day, he’s showing no signs of fatigue at all. Shaking hands, pinching baby cheeks, the activist priest has looked more and more legitimate as a candidate and politician every single day that I have observed him on the campaign trail. Now even I am starting to believe that a kind of real political miracle can come about in this beguilingly beautiful Cumbharjua constituency, and that we might actually be looking at the beginning of the end of politics as usual in this state.

Photo: Vivek Menezes

As Bismarque plunged into the assembled throng, I walked over to a cracked marble plaque on the face of a smashed monument. To my surprise, this was not an artefact from the colonial past, but the remains of a foundation stone that was laid here with immense ceremony just a few months ago, on 18 Nov 2011.

Through considerable defacement, I read the names of several top state politicians, including the notoriously extortionate PWD minister Churchill Alemao who has made a bridge to Divar one of his pet projects.

A local who strolled over now recounted how Divarkars boycotted this “ground-breaking” ceremony, then set about reducing the monument to rubble even before the ministerial vehicles could get safely back on the ferry to the main land.

Then this middle-aged voter again mentioned Asterix’s village, with a little confident shrug as if to say, “just let them try.”

That is the precise moment when I started to believe that Bismarque really does have a chance to pull off the most improbable upset in the history of Goa elections.