God and sometimes the voice of God. He plays stress-buster, therapist, family and business advisor, and the man with all the answers: marketing, yoga, TM, world peace, FMCG goodies, miracle healing, salvation from existential dilemmas. He (it’s mostly a he) is also often the object of secret envy. Though claiming a touch of other-worldliness, he’s so blatantly of this world and totes all the toys that boys like—and in such abundance that it fits most common fantasies. And if there’s a whiff of cultic fanaticism at one end, at the other he also possesses that ultimate aphrodisiac: political clout. So, it’s always a TRP-booster when a bad boy of babadom bites the dust as a common criminal.

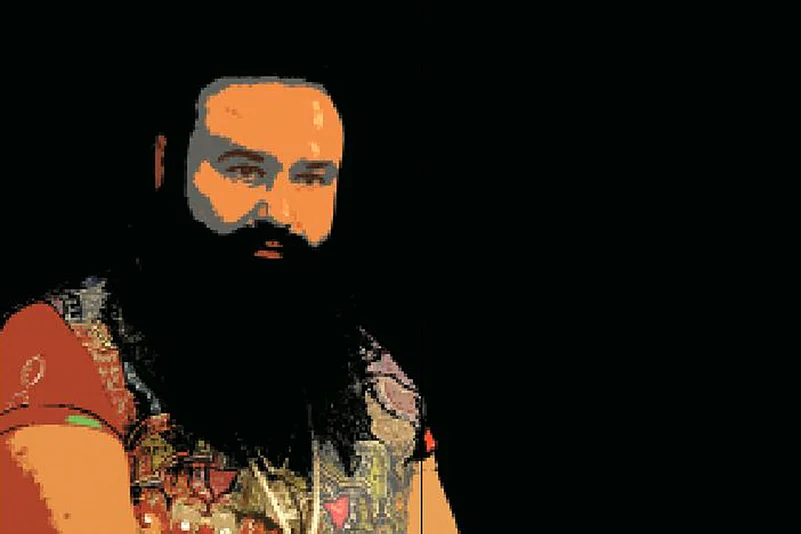

Viewers had their fill of exclamations and schadenfreude last week after the judicial gavel came down on a baba who looks straight out of a comic-strip but has deathly serious aspects to him: on his way to jail, he left a wake of corpses, injured followers, damaged property and a fistful of real heroes. Eyes remained glued to television and mobile screens as the ‘baba of bling’, Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh ‘Insaan’, leader of Dera Sacha Sauda (DSS), was first convicted and then sentenced to 20 years, along with fines, for the rape of two of his former devotees. The anonymous letter that finally led to the conviction described the rape scene as out of a Bollywood B-film, with a pistol on the bed and a pornographic film playing on a TV screen.

A full accounting of what went on at DSS may not be possible—the tales are legion. One case that has resurfaced is that of a man from Jaipur whose wife was escorted out of their room at the Sirsa dera one night and never returned. After futile attempts to lodge an FIR at a Sirsa police station, he tried from Jaipur. The Rajasthan police eventually filed a closure report with the court and the court was about to rule on the closure, when the rape trial concluded and led to the conviction.

Possibly the first conviction by Indian courts of a godman for raping his followers, ‘Insaan’ is in fairly quasi-divine territory. Babas of all hues and religious persuasions have been branded with sleaze and worse. The common thread is the bouquet of spirituality on offer for the seeker, criminality to lace his pockets, a lust for real estate, a protective entourage, fanatic followers and politicians bidding for their boroughs of influence.

Sins Of The Swami In 2014, Asaram Bapu (real name: Asumal Sirumalani) was put behind bars after a spate of allegations of rape and other crimes against him.

A similar media blitz was last seen exactly four years ago when rape allegations were levelled against Asaram Bapu (real name: Asumal Sirumalani). It’s difficult to erase the imagery piqued by news reports of the godman being administered a ‘feather test’ to rule out any chance of erectile dysfunction before proceeding with a rape trial. Asaram would allegedly throw a fruit at a female follower to mark her for his women apostles to deliver to his ashram for an ‘anushthan’. His son Narayan Sai (also later arrested) had an overactive libido too.

The rape allegations against Kripalu Maharaj, a godman from Allahabad, portrayed a scene no less cheesy, with dialogues like “Tu mera premi, aa gale lag ja” apparently sending female devotees into a hypnotic trance. Later, older female disciples would tell them they had been “blessed with pure devotion”. The accounts started flowing only when a case was filed in Trinidad and eventually dropped for want of evidence.

The Fallen Guru A rape case was filed in Trinidad against Kripalu Maharaj, a godman from Allahabad, and later dropped for want of evidence.

In 2011, Kripalu Maharaj’s successor, Prakashanand Saraswati, too was accused of molesting a minor. He jumped bail and tampered with the evidence, but was later convicted in absentia with a 280-year sentence. It’s believed he made it back to India with a fake passport. In a later account, the survivor described the cultist mentality of her mother, who had told her that she should “just enjoy it”.

Why do people flock to the garish Ram Rahim, with his put-on ghetto gangsta vibe, superhero flicks and pop ditties like Love Charger that claim an anthem-like appeal among devouts? There are social reasons—the dera movement’s origin in Punjab’s Dalit matrix, as an alternative to elite-controlled panthic Sikhism, is now well attested (The Dera Sultanates, p 46). There are also, of course, spiritual reasons. Says Jyotirmaya Sharma, author of several books on Hinduism, “The basic charisma that draws followers to cults is that they can have a two-way communication with God, who otherwise doesn’t answer directly to their prayers. Within the ascetic tradition, the godmen are seen as an incarnation of a God.”

The social genesis fades into the background as the gurus attain at a stratospheric level of popularity and enter the pop-cult world where new seekers of truth need merely to flip out their smartphone and access social media apps to see posts from their gurus. But a retrospective glance is illuminating. Ram Rahim inherited DSS in 1990 from his guru under a cloud of controversy. Some say DSS’s popularity is an index of a government push against the waning Khalistan influence. “He targeted Mazhabi Sikhs and then broadened his base. Gurus know what to offer a consumer and have a cafeteria-like approach with a variety of products from which you can select. Some sell yoga, some meditation and so forth,” says Bhavdeep Kang, author of a book on godmen, Gurus.

The Sikh radicals describe him as the government’s Frankenstein. “Following the green revolution, landless people felt neglected and the SGPC did not evolve any mechanism to include them in mainstream Sikhism. The Dalits found solace, fulfilment of basic needs and a way out of social evils at the deras,” says Kanwarpal Singh, spokesperson for the pro-Khalistan group Dal Khalsa. Ram Rahim claimed to have set up ‘orphanages’ within his ashram, but without any official clearance. The dera had hitherto barred Haryana’s women and child department from inspecting these ‘orphanages’. Only when he landed in custody did the department finally write to district authorities who transferred the orphans to state-run institutions. Amongst them were around 20 minor girls. The dera also ran residential schools and colleges within its borders. Police sources claim there was a direct passage from the godman’s residence to a girls’ hostel.

Latter-day godmen are of course a kind of genetic mutant emerging out of the old sects and reformist movements. Having lost touch with their social context, they soon forfeit the spiritual one too. Flip the pages and there is evidence that every corner of India has recorded tales of babas exploiting their flock, committing crimes with self-proclaimed divine indemnity and political quid pro quos. This last aspect particularly attracts notice, because it challenges the construct that a godman only feeds the spiritual void or social alienation.

And yet the connection between the spiritual and temporal may be nothing new. “The general foundational assumption is that a godman of whatever variety must be above worldly considerations and politics and must dispense spiritual solace. But since ancient times, godmen have always competed with each other for lay members, donors, benefactors and royal patronage. Many godmen couldn’t have formed their cults without royal patronage,” says Sharma. “From 19th century on, the modern nation state that developed needed an alignment with spirituality but that cannot be done explicitly. If spirituality becomes a threat to the state, the state will not tolerate it.”

But what one gets now is increasingly caricaturish versions—often you can trace the arc even within one entity. A godman named Sat Saidata had set up an ashram at Charkhari in Mahoba, Uttar Pradesh, circa 1900. In this village of Dalits, he offered them his name and they took it on as a surname. The village revered both him and his successors. The fourth successor was more ambitious. In 1999, he convinced a devout old woman to commit sati. “A sati memorial would have drawn more followers. So, the godman was upfront about telling me that he convinced the old woman, whose alternative was to live at the mercy of daughters-in-law and relatives. He was later arrested,” says Sharma.

Dead Man's Tales Ashutosh Maharaj’s ashram has been embroiled in controversies since his death in 2014. His body is in a freezer, with devotees insisting he is in ‘samadhi’.

Or take ‘Freezer Baba’ Ashutosh Maharaj. Born Mahesh Kumar Jha, he had left his home and became an ascetic in 1973. A decade later, he set up an ashram in Noor Mahal near Jalandhar that soon started attracting migrant labourers from Bihar. In January 2014, the godman died, but his trust claimed he had only gone into ‘deep meditation’ and would eventually come out of it. They brought in a commercial freezer and kept him in it. In mid-2014, when this reporter ventured into the ashram, it took four rounds of frisking and security checks (the last by the Punjab Police). Approaching ‘Freezer Baba’ or his abode was impossible, the trust’s functionaries said. The son, Dilip Jha, eventually approached the courts to cremate the corpse so as to claim succession. But the Divya Jyoti Jagran Sansthan would not let go of the corpse. At stake was an estate worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

The followers of Balak Brahmachari in Calcutta were not as lucky. In 1993, the godman died in a hospital and his devouts brought back the corpse to his ‘Santal Dal’ ashram in Sukchar, a village in Hoogly district. The held it hostage for 55 days, claiming he was merely in a trance and an awakening was imminent. The administration served several notices in vain. Eventually, the police broke open the gates one night, confiscated the rotting corpse and took it for cremation.

But the comic aspects divert attention from the real damage potential—the mix of politics, violence and legal immunity. By the 2000s, for instance, Asaram’s clout was quite visible. He used to circulate a pamphlet showing chief ministers, union ministers and opposition leaders bending at the waist, palms joined in a salute or touching the godman’s feet. “How can such a man be treated like a criminal? Bapu swayam bhagwan hai (he is God himself),” says a lawyer linked to the ashram.

Such absolute faith soon turns murderous. After Asaram and son landed in custody, new cases emerged—witnesses getting bumped off—and old cases surfaced. Ex-followers turned up to depose about murders, disappearances and occult practices. The parents of two boys who disappeared from an ashram in Madhya Pradesh in 2008 found public support. The Supreme Court recently issued notices to all states to set up guidelines for witness protection in India based on a petition by Mahendra Chawla (Sai’s former aide) and the fathers of two complainants. Meanwhile, a probe into Asaram’s tantric practices lies sealed with the Gujarat government since 2013.

Spurts of violence both seem to come naturally to cults and also occasionally cause their downfall. In 2013, followers of a self-styled Kabirpanthi godman, Rampal Singh, clashed with Arya Samajis outside his ashram in Rohtak, Haryana. Three people died. A year later, when the Punjab & Haryana High Court issued an arrest warrant, the police could not execute it for two weeks as the godman holed up in his ashram, protected by a human chain of thousands of women followers. A hundred policemen, 70 journalists and 30 others were injured in the clash that followed and Rampal was arrested the next day. The violent streak was in evidence again as his followers disrupted a courtroom while proceedings continued.

Patiala lawyer Harinder Pal Singh Verma, the CBI special prosecutor against Ram Rahim since 2007, once had a car of dera followers hit his vehicle from behind, though he was unhurt. During the trial, a lawyer-follower of the godman also issued a death threat to him while proceedings were on. There are also two murders—of Ranjit Singh, a brother of one of the rape survivors, and of journalist Ram Chander Chhatrapati, who had published the rape victim’s letter. Singh’s father and Chhatapati’s son are witnesses so the CBI feels it has a good case. “Ram Rahim’s freedom was directly connected with these deaths, so he is being tried for conspiracy,” says Verma.

Senior advocate Anupam Gupta, as amicus curiae, recalled an army intelligence input that had said former military personnel were imparting weapons training to DSS followers. Noting the impending rape and murder trials, Justice M. Jeyapaul too had said the dera should be searched for weapons and its activities monitored. The apprehension came true—it was all live on national TV on August 26.

Similar mayhem was seen last year in a state-owned horticultural garden in Mathura, UP, where a breakaway faction of the Jai Gurudev cult had set up shop for two years—running a country within a country. The original Jai Gurudev passed himself off as Subhas Chandra Bose, drawing on the popular theory that he was alive. Pankaj Yadav took over from him—and Ramvriksh was a malcontent unhappy at being sidelined.

After failed attempts to enforce a ‘Netaji’ currency, Ramvriksh gathered followers—mostly old tribals and Dalits from eastern UP and MP—and started marching towards Delhi. Midway, he was given space in Mathura. The commune had a ‘national song’, a school and other facilities but the core team was secretly stockpiling weapons. When police broke through the garden’s wall, a gunbattle raged till someone set fire to the huts and those in them. Thus ended the devotion of some. Those who, as Kang says, “make an investment in the guru’s purity even more than the guru”, for whom “anything that impugns the purity of the guru is unacceptable”.

Trouble is, this is a homicidal sort of purity. In Ram Rahim’s case, there are older murder cases that may now resurface. In 2008, the godman’s bodyguards had fired at a crowd of Jat Sikhs at a Mumbai mall, killing Balkar Singh and injuring others. In 2007, a former driver of Ram Rahim had confessed that the godman had allegedly ordered his former accountant Faqir Chand’s murder. The trail had gone dry in both for want of witnesses. “This one conviction will change things because the courts have ended the state patronisation of the dera,” says Kanwarpal Singh.

While the protective umbrella is there, of course, the ashrams exhibit an enviable GDP rate, often ending like Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, who is said to have had Rs 50,000 crore worth properties, or any of the southern spiritual ‘empires’. Says activist Sreeni Pattathanam, speaking over phone to Outlook from Kollam, “New-age gurus have corporatised spirituality. They jet-set and live lavishly. They use spirituality to create empires. Political powers and big business are beholden to them. Most of them avail tax benefits as charitable institutions. Their account books should be made public. But governments are afraid to touch them because they are afraid of the devotees who make up a sizeable vote-bank.”

And what happens to the dera’s mini-empire in Sirsa? The children have control as of now, but after the government and judiciary are done with its assets, there may not be much left. And Ram Rahim’s followers may carve out a place in Delhi’s Jantar Mantar, squeezing into a tent somewhere between the respective followers of Asaram Bapu and Sant Shri Rampal.