Even his critics can’t help occasionally, if grudgingly, admire his political savvy; his fans of course can’t stop gushing with his praise. Four years after he propelled himself onto the national political scene, Narendra Modi continues to be what he can be at best—a polarising figure with many capabilities and also worrisome dimensions. As he completes half of his full term, Modi continues to elicit huge expectations and deep concerns. It was said that Modi would set aside his controversial political career in Gujarat and make his mark on history as prime minister of India. What does the scoreboard say?

Becoming the PM itself has been a feat—winning clear majority almost single-handedly. That Modi came via the tough route—working at the state level as CM—is not really very special. Morarji Desai, Charan Singh, V.P. Singh, Narasimha Rao and Deve Gowda were all chief ministers once. But the crucial difference still remains—except Gowda, all others did have considerable experience as ministers in the central government before becoming the PM. And Modi’s relative newness to New Delhi’s politics certainly sets him apart from all his predecessors. Also, he belongs decidedly to a post-Nehruvian political era, a new elite, few of whom have so far made a real impact at the national level. Both these characteristics set him apart.

Image and popularity

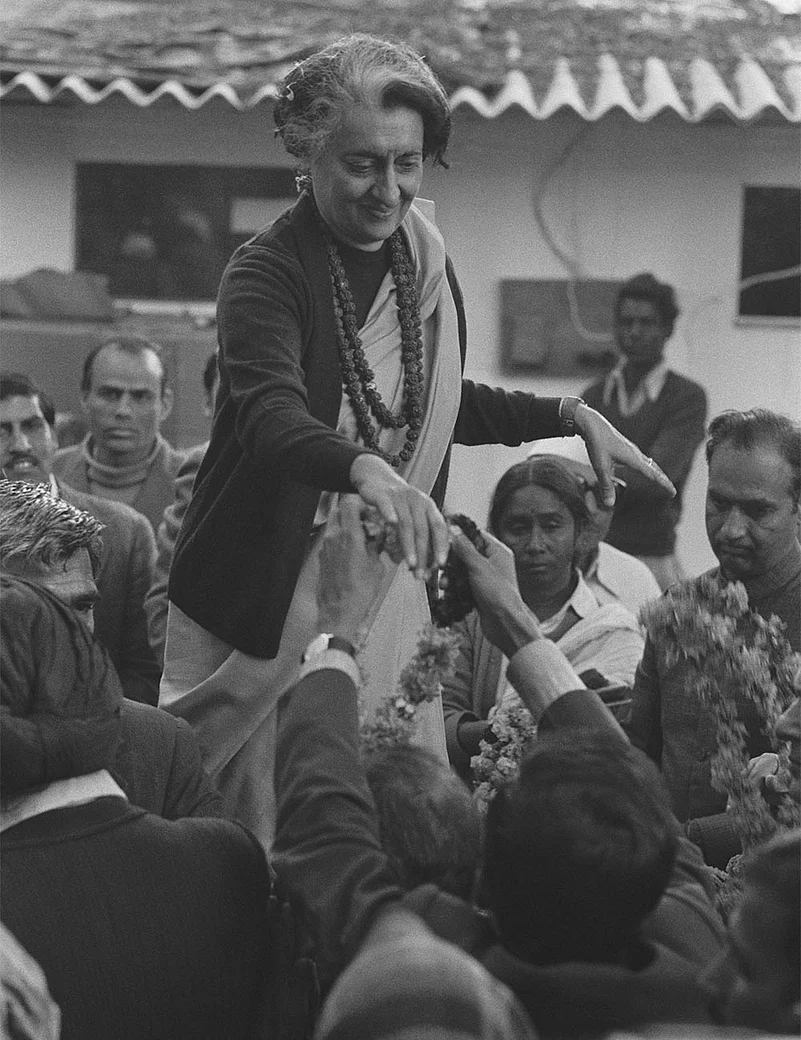

Modi rose to all-India prominence in early 2013. By that time, for a full decade, India had had a prime minister who was the least audible one. In contrast, Modi has been the most voluble and visible one. Besides, for more than two decades, there was no towering leader in the country. Rajiv Gandhi tried to be a ‘leader’, but he could not grow much beyond the reflected glory of his mother. So, in the real sense, post-Indira, there was no towering all-India leader at the helm. In principle, as Dr B.R. Ambedkar presciently told the Constituent Assembly, ‘idol worship’ is a danger from which democracy needs to be protected. In reality, democracy makes room for and produces among the public a desire for tall leaders, demagogues, populist crowd-pullers and charismatic personalities. Three decades of politics without a towering leader had left the popular imagination craving for a strong leader. Modi seized that opportunity.

He came to power riding on personal popularity—something akin to a ‘Modi cult’. Half way through his term, Modi’s personal popularity has remained more or less intact (going by some analyses). This is no mean achievement. In her post-1971 term, popular unrest was staring Indira Gandhi in the face by 1973-74. Rajiv began with goodwill and expectations, but by 1987, his ministers had started deserting him and his image began to get tarnished. In comparison, Modi’s mid-term report card would be strong on the question of popularity. This success is due to many factors: his ability to fill a continuing leadership vacuum due to the absence of a competing popular figure among his opponents, his penchant for seizing the initiative, his combative style and, of course, in no small measure owing to his communications skills.

Modi’s raw polemics riding on his demagoguery connects him easily to the masses. His speeches also make his rhetoric appear plausible despite the obvious difficulties stacked against the promises he makes. Logic is not the strong point of his demagogic rhetoric, but the logic of emotional appeal (for instance, “maha yagna against kaala dhan”) inspires confidence in him among his audience. And technology and an efficient public-relations machine orchestrate his larger-than-life image. It would be fascinating to watch whether the real Modi gets trapped into or overshadowed by the oversize image he has so assiduously constructed. But this ability to connect, communicate and create temporary conviction among the audience is central to Modi’s politics so far.

Politics, alas, is more than image-making. What is Modi’s record on some tough tests?

First, have there been any initiatives that he seized?

The measure of a good leader is to create opportunities. Modi came to power claiming that his predecessor was not only ‘maunmohan’ but a prime minister afflicted with ‘policy paralysis’. Modi assured energy and drive in making policies. Has he lived to that promise? His supporters may flaunt many such initiatives that are clothed in attractive acronyms and taglines. But let us look at some key initiatives that he began to take and faltered or messed up.

Modi has one undying ambition: to replace Nehru as the architect of a new, strongly nationalistic India of the future, one that’s firmly corporatised, though, and not socialistic.

In the realm of foreign policy, Modi began with a bang. Right from his first invite to Nawaz Sharif to that dramatic (dramatised?) Pakistan visit, an atmosphere was created that he is taking an extraordinary initiative in normalising Indo-Pak relations through personal charm. Soon, that hawa petered off; relations strained; cross-border clashes became more frequent and ugly; and India’s Pakistan policy entered a decade’s low, with ‘surgical strikes’ trumpeted as the new initiative. If there was an ironical contradiction between breaking bread with Sharif and the warlike rhetoric of surgical strikes, it was lost on observers. But that surely is an instance of false initiative. The other failed initiative related to Jammu and Kashmir. Modi spent his first Diwali (as PM) in the Valley, brokered an alliance with PDP—a first of its kind for his party, but could not take that détente to its logical advance. If anything, the militancy and popular unrest in the Valley has only reverted to the situation of mid-1990s.

Reams have been written on demonetisation, dividing the opinionated classes, but the political bottomline is obvious: Modi regime has come out as a regulation-happy big brother or an establishment that recklessly seeks to enforce a new turn of the capitalist economy or both! And two years down the line, what remains of the PM’s Red Fort speech of 2014 exhorting Indians to dedicate themselves to the cause of Swachh Bharat is nothing much beyond stray reports of villages free of open defecation. These INStances only suggest that publicised initiatives do not remain sustained targets of policy implementation.

Two, how has been Modi’s performance on key promises and expectations?

Modi’s campaign made two core promises. One pertained to economic development (achhe din); the other related to inclusion (sab ka saath sab ka vikas). Economists would keep debating the nature of economic performance, but ‘Make in India’ has not taken off, the GDP has not been buoyant and unemployment is on the rise. At the level of perceptions (and Modi certainly cannot complain about this criterion because his victory was primarily based on the shaping of perceptions), polls indicate that people are getting disappointed with the non-delivery of achhe din. As for inclusiveness, while inclusion in the fruits of development remains a challenge, frequent murmurs over ‘love jehad’, targeting of opponents as Pakistanis, fanatical pursuit of beef ban and the abominable harassment of Dalits in Gujarat are singular instances of exclusion of the minorities and Dalits. The PM has not done anything to indicate he does not want these to happen.

Three, has the PM strengthened institutions of democratic governance?

Setting aside anecdotes of the proverbial ‘third eye’ of the PMO monitoring everything and anything (which, in any case, manifests a degree of overconcentration), there is very thin concrete evidence of institutional consolidation. The government’s relations with the judiciary have become sour; Parliament continues to be mostly non-functional and devoid of debate; a Lok Pal is not yet appointed; shrill politicisation of military actions has unnecessarily dragged armed forces into controversies; but above all, the fiasco during demonetisation is being quietly blamed on the system. All this only vitiates and weakens institutions and makes democratic governance illusory.

After Indira Gandhi, India has not seen a towering all-India leader at the helm. Three decades thence, the present prime minister has seized that opportunity.

Four, how does he relate to his party?

Modi has rejuvenated the BJP beyond recognition. His 2014 campaign ensured that the party truly became ‘all-India’ geographically, and more than that, it firmly exited the traditional tag of being the party of the urban upper castes. While this was an outcome of a long process, Modi must be credited for this new life the BJP gained after two humbling defeats of 2004 and 2009. With political success, the party has also extended its advantage to the cultural and ideological arenas. So, during the past two-and-a-half years, the party and its web of sympathisers have mounted a sustained offensive against liberal nationalism, moderate criticisms and left-of-centre worldviews. It has systematically connected the ideas of development, nationalism and Hindu cultural assertion. The credit for this might go to the RSS and its many affiliates, but there is no point denying that Modi has been the central figure making all this possible. His leadership, his rhetoric and his political successes have created a strident BJP. How sustainable an overcentralised party model would be is a question, though.

Finally, whither Modi: statesman or smart politician?

Much would depend on where Modi goes from here. Whatever happens to immediate electoral contests, political debates in India would never be the same again. Modi has shifted the terrain of those debates. On questions of seizing the initiatives, Modi the politician has shown the importance of risk-taking. On fulfilling promises, his defence would be that the effects of his policies would be manifest only gradually—and whether or not achhe din have really come, there is no mistaking the historic place that Modi may have already reserved for himself: for the first time, India has a leader who staunchly and explicitly combines in his rhetoric and his policies the capitalist argument and the cultural argument of Hindutva.

Two-and-a-half years in power is surely a short time to judge a project such as Modi’s. But what about the long-term identity the pradhan sevak would hope to have? In the context of India’s political history, Modi has one undying ambition—to replace Jawaharlal Nehru as the measure of a democratic leader and become the architect of a new, strongly nationalistic and firmly corporatised India of the future. It is just possible that instead of becoming the Nehru of that future India, Modi would end up falling into the Indira mould.

On a more generalised plane, halfway through his term, Modi is at the crossroads: striving to carve out a place for himself in the pantheons of statesmen, yet constantly being pulled back by the persona of a smart, successful but assertive, polarising politician.

(The writer taught political science at Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, and is currently the chief editor of Studies in Indian Politics.)