On July 1, 2024, I found myself in one of the trial courts of Delhi, waiting for my case to be called. As I was waiting I could not help but overhear some lawyers to my side discuss arguably the most important legal development for half a century in India’s criminal process — the replacement of the three criminal codes with new, ‘decolonial’ ones which are supposed to fix everything and usher in ’90 per cent conviction rates’ in cases which will finish in three years.

These old hands were not curious about the nuances of the definitions which had been changed in the law, or what new crimes were now punished, how police powers had been expanded, or just what procedures had been altered to deliver on the three-year promise. The only thing that mattered was how long they really needed to get to grips with this new workload of having to re-learn the basics. A year was the consensus, with the real learning only needed for procedural laws.

It might feel odd reading a piece that speaks of continuity when most others are speaking about change — “10 Progressive Developments in New Laws”, “Comparative Table Explaining Changes”, “New Criminal Laws Usher Regressive Changes” and so on. Of course there are changes, albeit not many, and while some of them are good, many of them are problematic. Yet another piece telling us this may not be strictly necessary.

What I want to bring to your attention instead is the theme of continuity amidst the change. The truth is that the introduction of the new criminal laws is quite unlike other moves by the government to which it has been likened. This is not demonetisation, where the old must make way for the new, and must do so within a fixed time limit. Instead, the criminal process will now function in a peculiar duality. The old and new orders will coexist forever, neither will prosper, and it is the ordinary citizen who will suffer.

Harsh Realities

At a time when many quarters are sounding the alarm on the new criminal laws and the changes they bring, not much has been said about this bizarre dual-toned future which awaits us. It is only cases registered after July 1 which would be governed by the new procedural laws. Everything else will continue to be governed by the old codes.

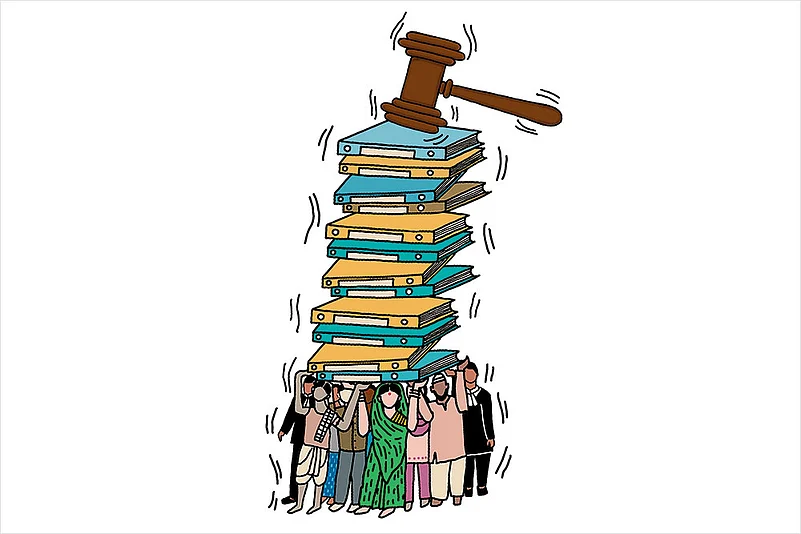

What is ‘everything else’? Let us look at the numbers — more than three crore criminal cases were pending at the trial courts when July began as per the National Judicial Data Grid, and all of these would continue to be governed by the old procedures. Then there are the appeals in these cases, which may be at the level of the Sessions Court, High Court, or even the Supreme Court. Let that sink in for a minute. The average pendency percentage of trial courts as per NCRB data for 2022 was at 89 per cent. It is reasonable to assume that it will take more than a generation to witness the closure of three crore cases, and more, by our courts.

The criminal process will now function in a peculiar duality. The old and new orders will coexist forever. neither will prosper, the ordinary citizen will suffer.

A changing of the guard is extremely common practice in law. But even where the small-scale changing of the guard took place, it took years for the cases under the old law to finally finish. Look around in the right places and you will still find cases lumbering along under the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act of 1974 (repealed in 1999), and the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities Prevention Act of 1987 (repealed in 1995). The only example of changing such a fundamental legal regime can be found in the Criminal Procedure Code of 1973 replacing the old Code of 1898.

Surely if we did it before, we can do it again, right? I am not so sure that this is the lesson which can be drawn from the past, for three reasons. First, replacing one pivotal law versus replacing three of them in one go makes the two events, frankly, incomparable. Second, the pendency rates in 1971 were a measly six and a half lakhs (for IPC crimes) as opposed to the two crore figure today, thus the scale of the disruption is arguably incomparable . Third, and while this is speculative, I would contend that the change of procedural regime arguably contributed to the exponential rise in pendency rates from the 1980s onward, with a yawning chasm emerging between the total number of cases instituted per year and those disposed of. One fears that we may be repeating the same mistakes less than half a century later, with disastrous consequences.

Fatal Inefficiencies

The government would like us to believe that the future is not so bleak as to be feared, but it is to be embraced, as it brings with it unlimited promise. A promise of technologically-savvy police investigations, speedy trials, and ‘just’ punishments. Whatever the promise may be, it is quite likely that its potential will remain unfulfilled because of the strain caused by the introduction of these new laws on all the stakeholders within the legal system. Judges, police officers, lawyers, everyone must remain fluent and familiar with not one but two rules of the game, to a level at which they must be ready to be flipping between these hats multiple times daily.

It may sound easy to the ear, but it is likely to cause immense hardship. Think of it from the standpoint of the police, or judges. The police will require training to implement these digitally savvy new laws. But, for quite a while, they will not be using this training or will be using it in tandem with old-school ways of doing things. Judges would be forever bound to the older codes even as their caseload grows with the new laws. And as time passes, more and more cases will arise where time will be spent deciding which regime will govern proceedings, entering hairsplitting discussions about how to interpret the repeal clauses, all of which will eat into the promised three-year time limit.

The criminal process is a setting where there ought to be no room for legal error as lives are at stake. In this zero-error setting, the introduction of dual realities will introduce boundless scope for trial and error as everyone feels their way about the room. As opposed to ensuring that the law maximises efficiency while minimising uncertainty, the government has set us on a path which exponentially multiplies inefficiencies and presents daily encounters with the unknown. It is not only going to dampen the ease of doing business, but it is likely to dampen the ease of enforcing personal liberty.

A Cause for Real Concern

The publicity blitz surrounding the introduction of the new criminal codes, or #AzadBharatkeApneKanoon, as the Press Information Bureau has pitched it, invites us to examine their merits in a vacuum. We cannot talk about the new criminal codes as if they will operate in a silo.

A non-functioning and comatose criminal process directly contributes to the popularity of rough and speedy modes of justice, represented by bulldozers and mob-lynchings, and making issues of arrest and bail carry more importance than determinations of guilt or innocence. It is no secret that the never-ending caseloads of our courts required attention and the government has played its hand. If the new laws do not manage to deliver on the promise of speedy, yet respectable, justice, but instead worsen the plaguing pendency crisis which has crippled the delivery of justice in our criminal courts, then we are in for tough times ahead.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Abhinav Sekhri is a Delhi-based criminal lawyer, and runs a legal blog proof of guilt

(This appeared in the print as 'Harsh Realities: BNS, Case Pendency, And Other Problems')