A study of outcomes of elections from 1951 and 1971— when parliamentary and assembly polls used to be held together generally, and separately only exceptionally—reveals that results were determined more by state-specific and national political issues and alignments of parties. Whether polls were held simultaneously or separately was not a deciding factor.

The Congress party—the political force which enjoyed an overwhelming dominance all over India during this period— used to

record a higher vote share in the Lok Sabha elections when compared to the simultaneously-held assembly elections in most states, even in its strongholds. This happened mostly because independent candidates used to get a higher share of votes in assembly elections.

On the other hand, the national opposition parties or regional forces did not necessarily benefit from separate elections, when state elections were held mid-term due to the reorganisation and creation of new states or because of the government losing the majority. There have been instances when, in the case of simultaneous elections, the Congress’ assembly vote share was about 5 percentage points lower than its Lok Sabha share. In some cases, their assembly vote share saw an increase in separately held elections.

However, it wouldn’t possibly be right to draw conclusions about the present political scenario based on the 1951-71 electoral trends for two reasons. First, the Congress was the main force not only nationally but in every state of the country. The current ruling party at the Centre is still trying to make inroads in many parts of the country where its electoral presence remains insignificant.

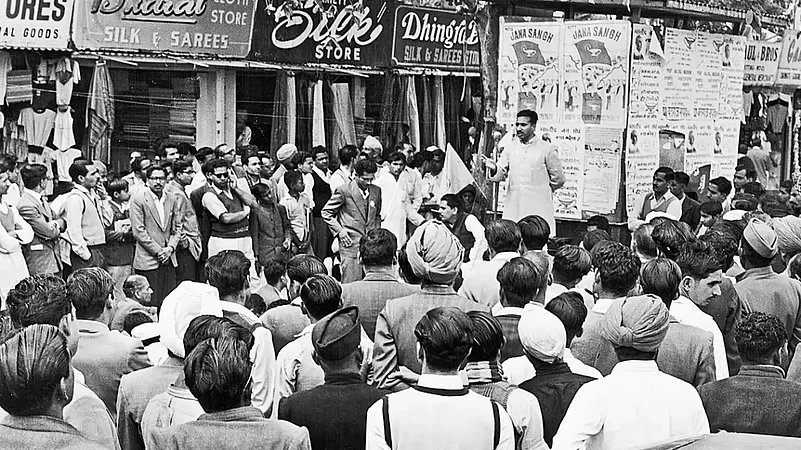

Second, the rise of strong regional parties is essentially a post-1960s phenomenon. National opposition parties like the Left (communists and socialists) and the Right (Bharatiya Jana Sangh, Ram Rajya Parishad, Hindu Mahasabha and the Swatantra Party) were strong in some states, but not strong enough to challenge the Congress-led state governments.

It is due to the lack of strong regional forces in many states that in the pre-1971 elections, after the Congress, the highest vote share often went to independents, more so in the assembly elections, whether held simultaneously or separately.

Take, for example, the states where the Congress faced some contest in 1951-52. In the Lok Sabha, the only states where it won less than half the total seats were Madras (35 of 75) and Rajasthan (9 of 20). Besides, the party won six of the 12 seats in the Travancore-Cochin states and 11 of the 20 seats in Odisha.

In the simultaneously-held assembly elections in these states, the Congress fell short of majority figures in Madras (won 152 of the 375 seats), Odisha (won 67 of the 140 seats) and Travancore-Cochin (won 44 of the 108 seats). However, the party managed to form governments with support from independents and other political forces. In Rajasthan, they crossed the majority mark by a very small margin—winning 82 of the 160 seats.

A look at the vote share shows that in Madras, the Congress polled 36.39 per cent votes in the Lok Sabha election and 34.88 per cent in the assembly election. In Travancore-Cochin, the Congress’ vote share in the Lok Sabha and assembly elections stood at 35.08 per cent and 35.44 per cent, respectively. In Rajasthan, the party’s vote share in the Lok Sabha and assembly elections stood at 41.42 per cent and 39.46 per cent, respectively.

In Odisha, the Congress’ Lok Sabha vote share (42.51 per cent) stood significantly higher than the assembly election vote share (37.87 per cent). A similar difference was recorded in the vote share of the main regional force, Gantantra Parishad (26.23 per cent and 20.50 per cent) and the pan-India entity, Socialist Party (15.40 per cent and 11.77 per cent). This can be attributed to the higher vote share of independents—8.65 per cent in Lok Sabha and 22.94 per cent in the assembly election.

Such trends were reflected even in states where the Congress party faced little challenge. In Bihar, the Lok Sabha vote share (45.77 per cent) was higher than the assembly election (41.38 per cent). But the main opposition party there, the Socialist Party (SP), had a similar gap—21.28 per cent in the Lok Sabha and 18.11 per cent in the assembly election, thanks again to the higher share of votes that independents secured.

Similarly, in Uttar Pradesh, the Congress’ vote share in the Lok Sabha elections stood at 53 per cent but in the assembly election, it was at 48 per cent. In Saurashtra, the party’s assembly election vote share—at 63.79 per cent—was lower than the Lok Sabha high of 66.36 per cent votes. In Bombay, the Lok Sabha election vote share stood at 50.15 per cent and the assembly election share at 50.04 per cent.

The 1957 election revealed a similar trend. In Bombay, the vote share of the Congress in the Lok Sabha (48.66 per cent) was the same as the assembly election share (48.66 per cent). But in Bihar, the party’s vote share of 44.47 per cent in the Lok Sabha was higher than 42.56 per cent in the assembly election.

In Madhya Pradesh, the Congress Lok Sabha vote share of 52.10 per cent was higher than the 49.83 per cent obtained in the assembly election. But the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) and the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS), the two main rivals in the state, also recorded a similar change in their vote share, thanks to the rise in the vote share of the independents in the assembly election.

Separate Elections

Travancore-Cochin was the first state to have a separate assembly election in 1954 after the government lost the majority. This separately conducted election saw the vote share of the Congress rising massively to 45.32 per cent from the 35 per cent share they received in both the assembly and Lok Sabha elections simultaneously held in 1952. However, in the concurrently held Lok Sabha and assembly elections in the newly-formed Kerala state in 1957, the CPI, with a 35.28 per cent vote share, won 60 of the 126 seats in the assembly and won nine of the 18 Lok Sabha seats with a 37.48 per cent vote share. The lower vote share in the assembly elections was because the party supported prominent civil society members as independents in more than a dozen seats. The Congress’ vote share, too, was higher in the assembly election (37.85 per cent) than in the Lok Sabha (34.76 per cent), though they contested a similar number of seats. The other national party, the PSP, also recorded a higher vote share in the assembly elections (10.76 per cent) than in the Lok Sabha (7.25 per cent) in the simultaneously held 1957 elections.

In the next mid-term assembly election held in 1960, the Congress, the PSP, and the Indian Union Muslim League formed a pre-poll alliance to counter the CPI and managed to reduce its seat tally. But the CPI’s vote share increased further to 39.14 per cent. Then, in the separately held Lok Sabha election in 1962, the CPI alone got 35.46 per cent vote share, another 3.61 per cent went to the CPI-backed Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP) winning candidate and three more CPI-backed independents won. Clearly, their vote share had risen further.

Odisha shows similar trends. In 1957, the Congress’ assembly election vote share (38.26 per cent) was lower than the Lok Sabha share (40.01 per cent). The vote share of the PSP, a national opposition party, too, was higher (15.40 per cent) in the Lok Sabha than in the assembly election (10.40 per cent). Once again, the independents had a role to play in this. The vote share of GP, which was the regional force, remained nearly the same—29.08 per cent in the Lok Sabha and 28.74 per cent in the assembly.

However, in the mid-term assembly election held in 1961, the Congress gained from the GP, which took its vote share to 43.28 per cent. The PSP’s share stood nearly the same at 11 per cent.

In the 1962 Lok Sabha elections, both the national parties, the Congress and the PSP, gained—the Congress’ vote share was at 55.53 per cent and the PSP’s at 15.5 per cent. The GP’s share dipped further.

The scenario in Bihar, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh, states that saw mid-term elections in 1969, was no different.

In Punjab in 1967, the Congress polled 37.31 per cent votes in the Lok Sabha and 37.45 per cent in the assembly election. In the mid-term assembly election held in 1969, the Congress’ vote share increased to 39.18 per cent. However, the merger of the two Akali Dal factions to form the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and a SAD-BJS pre-poll alliance reduced the Congress’ tally to 38 seats. The alliance, with a cumulative 38.37 per cent vote share, bagged 51 of 104 seats.

To draw a comparison, though the Akali and the BJS contested separately, their cumulative vote share stood at 39.5 per cent in the 1967 Lok Sabha and 34.5 per cent in the 1967 assembly election. The separately held assembly election did not help them in any way—what worked in their favour was the changed political equation.

In Uttar Pradesh, the simultaneously held Lok Sabha and assembly elections saw the Congress record a vote share of 33.44 per cent in the Lok Sabha and 32.2 per cent in the assembly. In the mid-term assembly election in 1969, the Congress recorded a similar vote share—33.78 per cent.

The main difference between the 1967 and 1969 elections was that a new party, Bharatiya Kranti Dal, was launched late in 1967, which emerged as the main opposition to the Congress in the 1969 election, securing 21.29 per cent of the polled votes, and eating into the votes of the BJS, Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP), PSP, Swatantra Party and the independents.

Nevertheless, the separate election and the new political developments did not impact the Congress’ vote share more than marginally.

In Bihar, the Congress’s vote share in 1967 was 34.81 per cent in the Lok Sabha and 33.09 per cent in the Vidhan Sabha. But its vote share dropped to 30.46 per cent in the mid-term assembly election held in 1969. The CPI, CPI (M) and the SSP had some seat adjustments in both the Lok Sabha and the assembly elections. The vote share of the SSP—which fielded candidates in two-thirds of the seats—remained the same in the 1967 elections. It stood at 17.83 per cent in the Lok Sabha and 17.62 per cent in the assembly election. But in 1969, the party’s share dipped to 13.68 per cent, even though they fielded candidates in almost a similar number of seats.

It was the BJS—and not Bihar’s main opposition force, the socialists (SSP and PSP)—that gained in the separately-held assembly election. In 1967, the BJS got 11.05 per cent in the Lok Sabha and 10.42 per cent in the assembly, but got 15.63 per cent in the 1969 assembly election.

In Jammu and Kashmir, the Congress polled 54.06 per cent votes under the Indira Gandhi wave of the 1971 Lok Sabha and further increased its share in the assembly election held the next year—55.44 per cent. In the assembly election, the Jamiat-I-Islami ate into the independent vote share, but the BJS’ 1971 Lok Sabha vote share of 12.23 per cent came down to 9.85 per cent in the 1972 state election.

(This appeared in the print as 'Tracking Election Trends')