On the evening of May 8, in a nukkad sabha in Raebareli, dozens of empty chairs stare at Congress supporters on stage. A property stands to their right; two graveyards spread nearby. A speaker, criticising Narendra Modi, stutters. A poet takes the mic and instructs the audience to pay attention, to clap, to egg him on. When nothing works, he heckles them. Nothing works.

Then, a name drops, and dhol beats rend the air. The seats fill; a crowd builds. Now there’s no space to sit. So they stand—near the stage, behind the chairs, on the wall—and wait. Not long after, she arrives, wearing sneakers and salwar kameez. Everyone stands; many take their phones out—restless to hear, clap, roar. Priyanka Gandhi? Nope, they react as if stirred by a storm, Priyanka Aandhi.

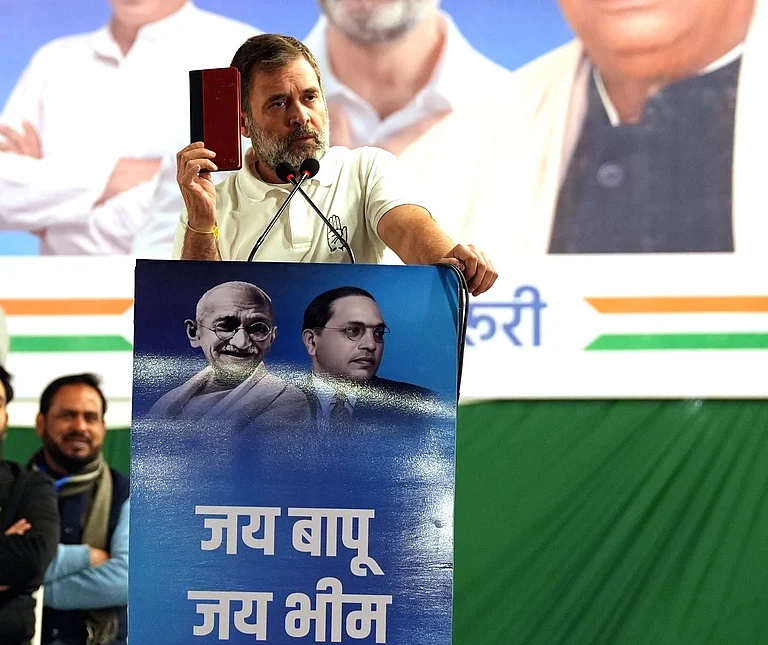

Indian voters usually reserve such a reception for a famous politician, but she’s never fought an election. She’s here, as always, to campaign for her brother, Rahul. Even though the stars no longer align for the Congress—in the last election, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won 62 seats in Uttar Pradesh, 18 more than the former in the whole country—one constituency continues to glow, Raebareli. It’s supported the Congress for decades, ensuring at least one seat in the country where the sun never sets on India’s grand old party.

Priyanka wastes no time. First: Modi’s promise (“2 crore jobs per year”, “farmers earning double”, “an end to corruption”). Then: the sellout media owned by big corporations parroting his ‘achievements’. “He’s sold everything to them: the airports, ports, coal, roads, power—all policies are made for them.” She sharpens her criticism: unemployment, inflation, falsehoods (referencing the recent “mangalsutra” claim). She unveils the Congress’ “guarantee”: “Increasing the minimum wage to Rs 400 per day, filling 30 lakh government jobs, relieving the farmers’ debts”—and half-a-dozen more. The crowd applauds. When she promises, “A law for [exam] paper leak”, a man says, “Bahut badhiya [wonderful].” Unlike most leaders, Gandhi neither deifies nor patronises her audience. She just talks to them—sometimes chides them. “They’re asking for votes in the name of religion—you’ve spoiled their habit.”

The Congress party has a Shah Rukh Khan-like effect on the people of Raebareli. When asked what it’s done for them, several of them pause and smile, as if to say, ‘What a thing to ask.’ Spread across different villages, they underscore the same reasons—“Rail Coach [factory], AIIMS hospital, [Sharda] canal, NTPC [power plant], a bridge over Ganga-ji”, and on and on—expressing their gratitude: “Whatever we’ve in Raebareli, it’s because of the Congress.” Some estimate the party’s chances in the coming election: “90%, 100%, 101%.” If their reasons to support the Congress find a huge overlap, then so do their discontent with the BJP: “unemployment, inflation, paper leak” and, by far the biggest, “stray animals”—such as cows and bulls—invading their farms and destroying their crops.

The Congress party has a Shah Rukh Khan-like effect on the people of Raebareli. When asked what it’s done for them, several of them pause and smile, as if to say, ‘What a thing to ask.’

The last nuisance gives the farmers literal sleepless nights, making them ‘chowkidars’ [guards]. The gaushalas, or cow sheds, don’t help either (“they take the animals in the afternoon only to let them loose in the night”). Earlier, the farmers could sell their unproductive cattle, but that option no longer exists. Because cows are gau matas now, rife with political meanings. Yogi Adityanath’s government tightened the screws in 2020 when, amending a 1955 Act, it banned the transport of “cow or its progeny” for slaughter and increased the punishment for the convicts: a fine of Rs 100,000 to Rs 300,000 and imprisonment from one to seven years.

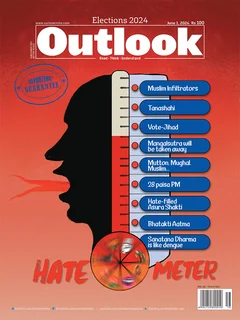

There’s another beast, though, that can tilt the Raebareli elections. “Hindutva,” says Jahnvi Patel in Bachhrawan, listing it as one of his reasons to choose the BJP. “Ram mandir. So many of our karsevaks were martyred for it.” Ram Chandra Dubey, a BJP supporter since the ’80s, likes the party’s “siddhant” (principles): the Ram Janmabhoomi, its 500-year history—something “no party” could rectify. “The BJP’s wave is rising. It’s not like the past where the Congress will win by a huge margin.” From 2014 to 2019, the BJP increased its vote share in Raebareli from 21% to 38%. Congress’ dipped from 64% to 56%. “Bharat has gone to the next level under the BJP,” says Raghvendra Singh in the Pakara Girafta village. “Ram mandir, Article 370, Ayushman card.” He rubbishes concerns about inflation (“people’s salaries have also increased”) and unemployment (“it’s existed for a long time, even during Congress rule”).

Such ideological determination, though, doesn’t come easy to all. At the BJP’s nukkad sabha in Khagipur Sadwa, Subedar Singh says, “No matter how much they shout, Sonia Gandhi did all the major developments in Raebareli. They’re lying that they built AIIMS.” He also talks about the stray cattle—and a ban on selling them—ravaging his livelihood. He’ll still choose the BJP though: “Dharam-karam ka lagaav [an attachment to religion].”

Something has shifted in Raebareli for sure. Jaffar, 69, an egg-seller in Bela Khara village, felt it earlier this year. On the day of the Ram temple consecration, he says, a group of Hindus chanting Jai Shree Ram slogans wanted to enter a gully adjoining a mosque. The Muslims requested them to use a wider road. They disagreed. Some women lay on the ground blocking their entry. A scuffle erupted. Three days later, the cops arrested Jaffar. “I wasn’t even there. I was here, at my gomti [shop], drinking chai with a retired soldier.” He spent eight days in jail along with 16 other Muslims—14 men, two women. “Should I be in jail at this age?” Jaffar asks. “I wasn’t even there, sir.”

Unlike the BJP supporters who praise its welfare schemes, many consider them inadequate. “Five kg grains aren’t enough to support my family of seven,” says Ashok Kumar. “I also need to buy vegetables, dal, salt.” Another farmer, refusing to be named, repeats the same reason. “The BJP government gives us five kg grains but causes harm worth 50 kilos,” says Kallu Sahu in Sulakhiyapur village. He points out a bigger problem: stray animals. “It’s good that they made Ram mandir. I’m a Hindu as well. But by releasing cattle, they’re killing us.” Kumar, too, sees no contradiction between his Hindu beliefs and economic concerns. “I understand that cows are as sacred as mothers. But stray cattle often get no water or food—canals and lakes have dried up—so if they’re dying on their own, then what can we do?” Their population has swelled so much that even cow sheds can’t keep—or protect—them. Right outside a gaushala in Bela Khara, several pits mark the barren land. So does the stifling rotten stench. It comes from a pit near the gate, where flies, insects, and maggots feast on decaying flesh: a dead cow whose left horn, still sturdy, silently screams hypocrisy and betrayal.

But there’s at least one village in Raebareli whose residents can’t sing the Congress’ paeans: Urwa, adopted by Sonia Gandhi in 2014. “No vikas has happened here,” says shopkeeper Rajesh Kumar. “Neither drains nor sidewalks. The taps are damaged; people drink polluted water.” His shop faces a field whose condition sums up the country’s current political narrative: a beautiful temple in the centre, trash lining its periphery, and an indifferent famous politician. In Urwa, though, personal is not political. “Many here still support the Congress,” says Kumar. He uses the word “chahat”—fondness—several times. “It’s this chahat that’s the biggest problem.”

His shop faces a field whose condition sums up the country’s current political narrative: a beautiful temple in the centre, trash at its periphery, and an indifferent famous politician.

In a house in the same lane, Rajmati sits on her haunches, repeating the same complaints: “No sidewalks, no water. We had hoped she’d make our village glow, but nothing—I mean, nothing—has happened.” Ten days before the election, she’s certain about her choice. “If she [Sonia Gandhi] wins, we’ll be glad.” Rajmati explains her apparent dissonance: “If she has no pakad [hold]”—a government at the centre—“then what can that bechari do? I don’t blame her entirely. Saath toh denge [I’ll still support her]. Because I understand her situation. She’s just like me: helpless.”

Around 90 minutes from Raebareli lies another Congress bastion, Amethi, where Rahul Gandhi lost to Smriti Irani in 2019. Shielding the scion, the Congress has chosen a veteran party coordinator, Kishori Lal Sharma, who has never fought an election. At a nukkad sabha in Bhimi, Sharma speaks in a soft tone, sometimes slips into self-deprecating humour. He glances at a sheet of paper, more than once, to collect his thoughts. He says, as if it wasn’t already clear, “I’m not an expert orator.” His speech trundles and rambles—staying in the ’80s for 20 long minutes—as the audiences tune out: they look at their phones, chat among themselves, smoke beedis. His next talk in Balipur Hudiya is as listless. And this continues, as this misfit flits from one village to the other: a gentle man in a cruel world, an art-house subplot in a Bollywood potboiler.

Irani, on the other hand, flings rhetorical questions. “How many of you took the Corona vaccine given by Modi-ji?” She asks in Mudupur. “So if Modi-ji saved lives then who should get the vote?” Next: “Since Corona, how many of you have got free ration? Now if Modi-ji gave ration, then who should get the vote?” Cut to: “Do you get Rs 6,000 per year under the Kisan Samman Nidhi? Modi-ji says if you press kamal ka button on May 20, you’ll keep getting Rs 6,000.”

She segues to a literal handout: “How many of you got prasad for the Ram mandir? No one refused it, right? But the Congress party did—did it not?” She goes on: how the Congress wants to undo the Ram temple decision, how it wants to ‘purify’ it. “I dare the Congress party to touch the flag in Hanuman Gadhi in Gauriganj.” The crowd chants: “Jai Shree Ram. Jai Shree Ram.” She accuses the “Congress’ goons” of stopping the “bhaagwat ki katha”, forbidding the devotees to ring the temple bell, and throwing Hanuman-ji’s statue in the lake. “So I’d say become democracy’s Hanuman and burn the Congress’ Lanka.” She leaves. The same script at the next nukkad sabha in Utelwa, Jagdishpur: welfare schemes, Hindu gods, Congress party—not a word about what she’s done as an MP over the last five years.

“She hasn’t done anything,” says Sarvesh Singh. One-and-a-half months ago, Irani visited a school in his village, Pindoria, in the Amethi Vidhan Sabha unit. “We handed her a huge stack of complaints. She solved one or two and threw the rest into the garbage.” He talks about the stray animals (“it’s a menace; the whole village is fed up”). They don’t just destroy crops—he camps in his field till three in the night—but also kill pedestrians. Standing beside Singh, 17-year-old Aditya recounts two such deaths (just like several locals in the town). “It’s not like I oppose the BJP,” says Singh. “It’s great that you stopped the killing of cows. But aren’t people more important than animals?” He likes the BJP, not Irani. “Had Priyanka or Rahul Gandhi contested from here, it’d have been a one-sided contest.”

Calling the handouts “lollypop”, Singh highlights rampant unemployment exacerbated by the constant “paper leak”. But, as usual, the BJP has a cheat code. “Those who oppose the Sanatan Dharma—the Ram mandir—are anti-national,” he says. The Pindoria villagers, he adds, would choose the BJP for just one reason: Hindutva. Ram Pher Singh, 75, voted for the BJP in the 2014 and 2019 elections because of “the Ram mandir, Modi and Yogi”. But now, he reels off his own discontents: the closure of the Indian Institute of Information Technology, the lack of medicines in the government hospital and, the one that enrages him, an unrepaired road in front of his house. “Modi and Yogi were good before, lekin ab tanashahi kar rahe hain [but now they’re doing dictatorship].” His voice drops, as if talking to himself: “Lekin ab tanashahi kar rahe hain.”

In Benipur, where Muslims comprise the bulk of the population, several villagers refused to reveal their problems or names (including a young unemployed man). “See this boy sitting here,” says one who finally spoke, Mohammad Akleem, “He’s a graduate but unemployed.” Akleem and a man opposite him, Nawaz Waris, echo the Pindoria villagers’ problems: an absent MP, paper leak, stray cattle. If Irani revels in her handouts, then her ‘subjects’ respond. “Do you think your five kg grains can buy us?” Akleem asks. “You tripled our problems. And you bulldozed more houses than you gave under the Awas Yojana.” Waris scoffs: “Sirf bhaukal-baaji [just show off].”

They recount a recent incident—very similar to Jaffar’s. Last winter, when the Muslims read namaz in the Ibrahimpur village, the Hindus began chanting Jai Shree Ram. “The imam requested them to not shout, as it was namaz’s time,” says Waris. “But they started pelting the mosque.” Then “vandalised a madrasa,” says Akleem. The cops arrested over a dozen Muslims. If even Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi haven’t been spared, adds Waris, “Then we, in their eyes, are no better than insects in a gutter.”

Crippling unemployment and stray cattle have forced many locals to supplement their incomes by opening shops (such as Kumar in Raebareli and Waris in Benipur), but that, too, has its own hassles. “Because of the big online players [such as Amazon], small shopkeepers struggle to sell their goods,” says Saurabh Gupta, an MSc graduate who, without a job, manages his parents’ store in Jagdishpur, around 50 km from Benipur. Promising tempting discounts, they’ve reduced his daily earnings from around “Rs 500 to Rs 200”. Ashfaq Ahmad, who owns a shop near the main road, suffers much higher losses. Because unlike Gupta, he and Jaffar share a unique problem: “Most Hindus no longer come to my shop. Earlier, 80% of my customers were Hindus—now it’s not more than 2%.”

The complaints against Irani continue to mount in the Tiloi Vidhan Sabha unit. Sant Lal, an electrician: an absent MP, inflation, stray cattle. Aman Kumar, a second year BA student: an absent MP, inflation, unemployment, paper leak, “no good colleges”. But Ram Chandra Singh, a retired Army professional, admires her work: “road, ration, light”. Like Raghvendra in Raebareli, he dismisses the unemployment issue: “There are jobs. If you can’t find them, then open a business. People who whine about jobs are just lazy.”

Around 35 km from Tiloi lies a village in Gauriganj, Poore Hundaliyan, whose residents get triggered at the mere mention of a word—the same word that deflates Rajmati and angers Ram Pher; a simple word, a basic need: “kharinja [side road]”. A battered brick road languishes in front of Binod Kumar’s house. “You can see what the BJP has done in the last 10 years.” Less than a kilometre away, he says, Irani has built her house. “The whole village is of Brahmins. And they all support the BJP—one-sided. But this time, it’ll not get one vote.” The kharinja has remained unrepaired for close to a decade. “We approached everyone: the Secretary, the ADO [Assistant Development Officer], the BDO [Block Development Officer], the CDO [Chief Development Officer], the pradhan, his representative. Application par application.” When it rains, the lane floods. “We wade through this much water,” Kumar points to his knees. Five years ago, his mother broke her leg. He had to transfer her to a different house because “no ambulance would come here”.

As Kumar and his brother, Satyendra Tiwari, shoot their complaints, their neighbour, Lallan Tiwari, stops by on a bike. “The district headquarters is just a kilometre away,” says Lallan. “The MP house 500 metres.” In multiple nukkad sabhas in Raebareli, the BJP’s candidate, Dinesh Pratap Singh, spoke about several new highways connecting the town. “We’ll reach them only if we can leave our homes. Highway, four-way, Chaubey, six-way—what’s their use?” Whenever they approach the pradhan for their kharinja, they get the same reply: “We don’t have the budget.”

Their anger boils and bursts, as they start slamming one government scheme after the other. First, Swachh Bharat Abhiyan. “Come, I’ll show you,” says Satyendra. On the edge of a small field stands a booth, barely 8/10 feet. Lallan opens the door. Inside: a dusty floor and an ‘Indian’ toilet whose right foot is dislodged. Satyendra opens the door of another toilet right next to it: clean, spacious, white tiles. “The villagers made it themselves.” He points to two more toilets opposite a kharinja: a government dump, an individual enterprise. These juxtapositions say something to Irani: Your charity, our dignity.

“Come,” says Lallan, “let me show you something else.” A new kharinja. “We made it ourselves.” A young man, Vijendra, who works in Nasik, highlights another scheme. “Kisan Samman Nidhi. I’ve taken my babu-ji so many times to Vikas Bhawan for his payments. We got nothing for three to four years.” Ashok Kumar’s father in Raebareli, too, hadn’t received his instalments in a long time. Lallan and Vijendra walk to a nearby house owned by an old, deaf woman. Vertical stacks of hay spread to the left and right of the small entrance. Its slanted roofs are made of clay and asbestos. A small tree juts out from a room inside. A bamboo pole runs from the roof to the floor in a different room. “See this support,” says Vijendra. “If this falls, they’ll be trapped.”

Unlike the old woman, her neighbour got a “colony”—a house—under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. “They had vyavastha [‘arrangement’],” says Kumar. “She has nothing.” Vijendra explains: “Mithai” [sweets]. “Earlier the money [for the Awas Yojana] came into the pradhan’s account. Now it goes to the customer. But he says you’ll get the amount only when you give me something under the table—mithai.” The kickbacks vary from “Rs 25,000 to Rs 35,000”, says Satyendra, for a Rs 1.5 lakh loan. A blue-collar worker, Dharmendra Kumar, had a simple question for Irani after her nukkad sabha in Mudupur. But he lost her in the crowd. “When I tried to get a loan for the Awas Yojana,” he told me, “I found out my application would only be forwarded if I paid Rs 20,000.”

“I’ll tell you something honestly,” says Vijendra. “Hindus and Muslims have no problems with each other.” He often visits the neighbouring village Misrauli for functions, which has a dominant Muslim population, and they come here. “They cook vegetarian food for us. We talk frankly.” The main problem is something else. “The Pradhan is a Thakur,” says Satyendra. “So is the Vidhayak. So is [Yogi] Baba.” Satyendra, Kumar, Lallan, and Vijendra keep repeating one point: that Irani’s house is so close and yet she hasn’t peeped into their village, not even once. “She’s making a highway near her house. We don’t have a kharinja,” says Lallan. “They’re installing solar lights at every crossroad. For what?” Seven-hundred metres, Vijendra repeats, the distance from his house to Irani’s. “There’s a proverb in dehaat bhaasha [rural lingo]: Chiraag tale andhera [darkness beneath light].”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Tanul Thakur in Raibareli and Amethi

(This appeared in the print as 'A Tale Of Two Citadels')