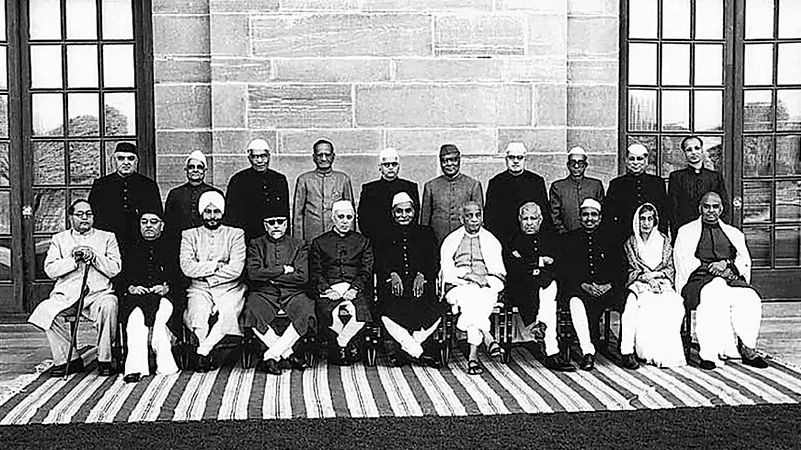

The gradual upping of the ante by the Narendra Modi government against the judiciary–led by law minister Kiren Rijiju and aided by the likes of Vice-President, Jagdeep Dhankhar, has reminded people of the Indira Gandhi regime which is when the judiciary-legislature conflict reached a tipping point. Between 1967 and 1984, when judges gave verdicts against the government on issues crucial to the ruling party’s policies, the government retaliated by interfering with judicial appointments and the judiciary acted in different ways–some judges standing firm, some allegedly ready to cleave.

The conflict between the two arms, or the possibility of it, is not new to India. In 2018, when India’s Attorney General, KK Venugopal, took potshots at the Supreme Court, saying that he hoped the concept of ‘constitutional morality’ died soon, he invoked India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru’s, apprehensions. His comments had come against the backdrop of the SC relying on ‘constitutional morality’ in the verdicts on high profile cases such as the reading down of Section 377 (homosexuals) and entry to the Sabarimala temple (menstruating women). “Unless it (constitutional morality) dies the former Prime Minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s, fear of the Supreme Court becoming the third chamber of the Parliament may come true,” Venugopal had said.

Some found it ironic that the AG had to invoke a prime minister whom India’s ruling force since 2014 have blamed and criticised the most. But in that Constituent Assembly speech on September 10, 1949, Nehru had strongly opined that “the legislature must be supreme and must not be interfered with by the courts of law in such measures of social reform.” That day, while speaking on the Congress’ commitment to abolishing zamindari or landlordism, he said that “no legal subtlety and no change is going to come in our way” and that “within limits, no judge and no Supreme Court can make itself a third chamber.” The ‘third chamber’ remark comes from calling the Lok Sabha the first chamber and the Rajya Sabha the second.

“No Supreme Court and no judiciary can stand in judgment over the sovereign will of Parliament representing the will of the entire community. If we go wrong here and there, it can point it out, but, in the ultimate analysis, where the future of the community is concerned, no judiciary can come in the way. And if it comes in the way, ultimately the whole Constitution is a creature of Parliament,” Nehru had argued.

Nehru, nevertheless, laid stress on the need to respect the Judiciary because he thought elected publicly representatives could go wrong in moments of passion and excitement. Then, the Judiciary, “in the detached atmosphere of the courts… should see to it that nothing is done that may be against the Constitution, that may be against the good of the country, that may be against the community in the larger sense of the term.” Even then, the Judiciary “should draw attention to that fact” but not “function in the nature of a third House.”

Nehru had also spoken of two ways to deal with times when the Judiciary came in the way of the Legislature implementing social reforms–one, to amend the Constitution; the other, the executive appointing judges. He deemed the latter as, “not a very good method” as it could mean appointing, “judges of its own liking for getting decisions in its own favour.”

Now, 73 years later, the debate has come alive again, with the government objecting to the apex court’s striking down of the 99th amendment to the Constitution in 2014 that sought to replace the Collegium system of judicial appointment with that of a National Judicial Appointments Commission, which would have given the Legislature a broader role in the appointment of judges.

Nehru himself had agreed to the idea of amending the Constitution—the first amendment coming as early as 1951 to ensure that the court did not come in the way of the abolition of zamindari, nationalisation of industries and businesses and ensuring special provisions for people from backward classes. It created the Ninth Schedule, wherein, once included, a law becomes immune to being challenged in court for violating the fundamental rights of individuals.

Nehru continued to tread the path of constitutional amendments, mostly regarding fundamental rights related to property and businesses that came in the way of his socialist reforms, aimed at a more equal distribution of wealth. This resulted in the insertion of more state and central laws in the Ninth Schedule— through the 4th amendment in 1955 and the 17th amendment in 1964.

Nehru did not publicly show any disrespect towards the Judiciary nor did he try to influence judicial appointments. But his daughter, Indira Gandhi, who stepped into his shoes two years after his death, had different ideas. Initially, she, too, tried the same path. However, she lacked the parliamentary strength in 1967 to successfully amend desired portions.

To add to her problems, the Supreme Court in the IC Golaknath in 1967, upheld the validity of the past amendments on the ground that they were validated by the court at that time but declared that the “Parliament will have no power from the date of this decision to amend any of the provisions of Part III of the Constitution so as to take away or abridge the fundamental rights enshrined therein.”

This order came as a major blow to Indira Gandhi as she was preparing for major reforms that could curtail fundamental rights on property and businesses. But more such blows were in the waiting. In 1970, the apex court declared the Banking Companies (Acquisition and Transfer of Undertakings) Act 1969 invalid, almost jeopardising the prime minister’s hope for nationalising banks on her own terms.

At that time, her government–following a split in the Congress–was standing with the support of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) in Tamil Nadu and the CPI. A few months later, in 1970, she tried to bring in the 24th amendment to abolish the privy purses, the tax-free income to which erstwhile princely estates were constitutionally entitled. It dramatically failed in the Rajya Sabha by one vote and then the government passed a Presidential order to effect the abolition. It was challenged in court and overturned. Soon after, she called for fresh elections and went to the people seeking a greater mandate so that she could freely implement her pro-people policies that would eventually undermine the fundamental rights of the wealthy.

She achieved a massive mandate this time and was apparently on a mission to prove parliamentary superiority over the Judiciary on the question of amending the Constitution. It resulted in a slew of amendments – the twenty-fourth amendment in November 1971 overruling the judgment in the Golaknath case; the twenty-fifth amendment in December to pave the way for bank nationalisation; and the twenty-sixth amendment the next year, to abolish the privy purses. The last two amendments happened at a time when the Supreme Court was still hearing the challenge to the twenty-fourth amendment.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court, in 1973, in Kesavananda Bharati, overruled the Golaknath verdict and held that the Parliament had the power to amend fundamental rights. The judgment also validated the 24th amendment. Widely held as a historic and balanced judgment, it held that “the amending power under Article 368 is neither narrow nor unlimited.”

In it, by a 7-6 majority decision, the court held that the power in Article 368 allows the Parliament to amend every article but not “to abrogate or take away fundamental rights or to completely change the fundamental features of the Constitution so as to destroy its identity.” This verdict gave birth to the ‘basic structure doctrine’ that the apex court has followed since then.

The Indira Gandhi government should have seen the verdict as a victory. The 24th amendment was validated and the court also agreed that the Parliament had power to amend the Constitution. However, she was evidently unhappy with the emergence of the basic structure doctrine. Her discomfort with, or rather disdain for, the apex court judges became evident when, for the first time since independence, the government decided to interfere with judicial appointments.

Going against the norm, the government appointed Justice AN Ray, who had held a minority opinion in Kesavananda Bharati, as the next Chief Justice of India, superseding three senior judges who were part of the majority verdict.

This was exactly what Nehru had dubbed as “not a very good method” of appointing “judges of its own liking for getting decisions in its own favour.”

All three judges superseded here resigned soon after but the government did not care. Buoyed with the confidence of having a favoured judge as the Chief Justice of India, her government introduced a slew of new amendments. Yet opposition from the Judiciary was far from over, as an Allahabad high court verdict in 1975 invalidated her election to the Lok Sabha. What happened next is well-known—the imposition of the Emergency and insertion of a slew of laws under the Ninth Schedule.

First came the 39th amendment, which not only took matters related to the election of the President, Vice-President, Prime Minister and the Speaker of the Lok Sabha outside the purview of the court but further proposed “to render pending proceedings in respect of such election under the existing law”–of course, including the invalidation of her own election—as null and void. This was done while her appeal against the high court order was still being heard by the apex court.

About the same time, the government had put forth the new concept of ‘committed judiciary.’

Next year, in 1976, came the 42nd amendment.

The Supreme Court did not come into much confrontation with the government during this period. Chief Justice Ray had a long tenure of nearly four years. Before his retirement, he led the verdict on the high-profile habeas corpus case (ADM Jabalpur vs Shiva Kant) that held that during Emergency, “no person has any locus standi to move any writ petition under Article 226 before a High Court for habeas corpus or any other writ or order or direction to challenge the legality of an order of detention.”

It also upheld the controversial provisions of the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) and offered huge relief to the Indira Gandhi government with regard to detention–which was its prime method of silencing political dissenters.

The story of this judgment does not end here. Justice H R Khanna disagreed with the majority and wrote a dissenting judgment, in which he opined that if the right to enforce Article 21 is suspended, there would be no recourse against the state’s deprivation of the life or liberty of an individual. This cost him the chair of the Chief Justice.

In 1977, ahead of Justice Ray’s retirement, the government picked Mirza Hameedullah Beg to succeed him, superseding Khanna. He resigned.

Several amendments that Indira Gandhi brought between 1973 and 1976 were later struck down by the Supreme Court but the ghost of an authoritarian regime subverting an independent Judiciary for centralisation of power has not ceased to cast its troubling shadow over Indians.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Splintering the Foundation")