The introduction of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) and Rahul Gandhi’s candidacy in Wayanad were two factors that played a crucial role in the United Democratic Front’s (UDF’s) remarkable victory in the 2019 Parliamentary elections. But this did not necessarily reflect any significant anti-incumbency sentiment, as demonstrated in the subsequent assembly elections where the Left Democratic Front (LDF) retained power with an impressive tally of 99 seats. In essence, the key takeaway is straightforward: people apply different scales for different elections.

The concept of One Nation, One Election (ONOE) appears highly implausible to constitutional experts and non-BJP parties in south India. According to P D T Achary, a constitutional expert and former Lok Sabha Secretary General, it is a notion that seems hardly feasible as it fundamentally contradicts the core principles of the Constitution. “The authority to dissolve a state government primarily resides with the state government itself. The governor’s recommendation for dissolution is typically based on the decision made by the council of ministers within that state. The Centre’s power to dismiss a state government is derived from Article 356, but this power cannot be exercised arbitrarily,” says Achary. He further argues that the implementation of ONOE goes against the basic structural doctrine—no constitutional amendment is possible if it goes against the basic structure of the Constitution—as it would result in burying the principles of federalism, a scenario that is highly unlikely to materialise.

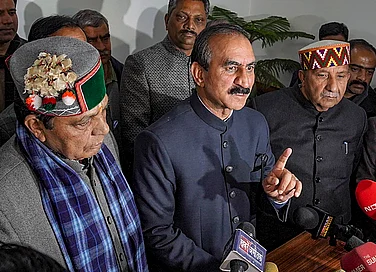

“The next will be one language, one leader,” says M V Govindan, state secretary of the CPI(M) in Kerala, and asserts that this is nothing but a campaign to sabotage the political and cultural diversity of the country—one step towards fascism. He also argues that ONOE may not be implemented, but will be used only like CAA and UCC to weaken the diversity of the country, and thus to achieve the goals of Hindutva.

Voting trends over the years have demonstrated that a combination of political, economic, historical and regional influences have played a significant role in determining how the south and north regions of the country vote. It’s important to note that the preferences expressed in state assembly elections may not always align with the choices made during Parliamentary elections. However, this is precisely the aim of the ONOE proposal, as outlined by political analysts. The proposal envisions a process in which elections for all state assemblies and the Lok Sabha are conducted simultaneously.

“While national parties like the BJP and the Congress campaign on national issues, it is regional parties like BRS, TDP, YSRCP and AIADMK that raise issues of the local people in their states. If ONOE is implemented, state-centric parties will be at a huge disadvantage,” says Surendra Kumar who teaches political science in Bangalore University.

Over time, it has become evident that the BJP’s strong ultra-nationalistic approach has not succeeded in resonating with the people in south India, as indicated by the voting patterns. The BJP has consistently failed in garnering a significant share of votes in both Kerala and Tamil Nadu since the formation of the party. In the 2016 assembly elections in Kerala, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) managed to get 14.46 per cent of the votes, which allowed the BJP to secure its first member in the legislative assembly. However, in the 2021 assembly elections, the NDA’s vote share dipped to 12.4 per cent, even though it was a period when the BJP was making its presence felt across the country with its nationalistic slogans and policies. The party also lost the single seat it had held in the assembly.

Unlike in Kerala, the BJP in Tamil Nadu does not contest independently, but has consistently allied with the AIADMK. In the 2021 assembly elections, the BJP won four seats, but was limited to a mere 2.6 per cent of the vote share. The ruling national party remains a relatively inconsequential partner in its alliance with the regional AIADMK. In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the AIADMK front, including the BJP, was decisively defeated by the DMK-Congress alliance, which secured a substantial vote share of 52.64 per cent.

Karnataka stood as the solitary state in south India where the BJP—under the leadership of Narendra Modi—managed to form a government. However, the party’s pronounced ideological stance on Hindutva proved detrimental in the recently held assembly elections, where the Congress achieved a resounding victory, winning 136 of the 224 seats. From fabricating narratives surrounding Tipu Sultan to imposing a ban on hijab within educational institutions, it appeared that the state had reached a tipping point in its response to the BJP’s strategic approach.

“The focus of national parties has always been about how the country got a new Parliament building, the elaborate preparations ahead of the G20 summit, etc. But why will a voter from rural Madikkeri in Karnataka vote for a party that only focuses on these projects?” asks Kumar. He also argues that the media focus would shift entirely to the national party’s narrative if assembly and Parliament elections are conducted simultaneously.

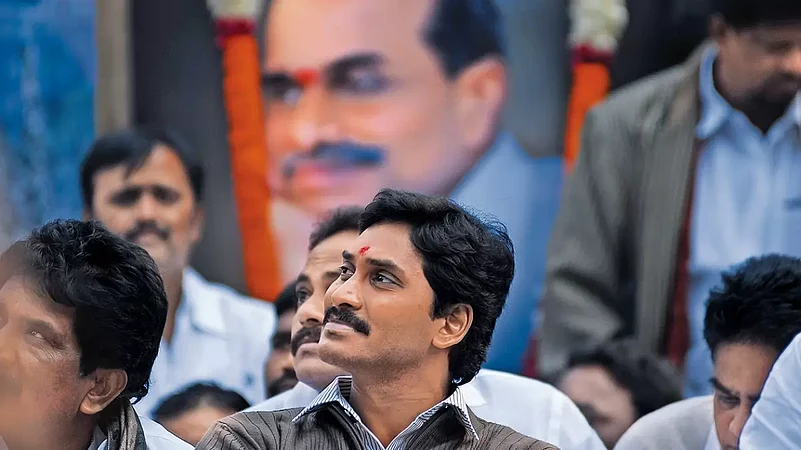

The experiences of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana further illustrate how nationalist slogans tend to get overshadowed by regional interests, even when regional parties form alliances with the BJP. In 2019, Andhra Pradesh conducted its assembly elections simultaneously with the general elections. Jagan Mohan Reddy of the Yuvajana Shramika Raithu Congress Party (YSRCP) defeated the TDP (Telugu Desam Party) and the BJP alliance. During this electoral showdown, the BJP and the Congress found themselves relegated to the sidelines, exerting minimal influence on the political landscape of the state.

“Since simultaneous elections had already been held in Andhra Pradesh in the past, a return to such a system would likely see voters continuing to favour regional parties,” says Ravichand of Hyderabad-based People’s Pulse, a group comprising politically engaged individuals working to understand ground-level dynamics.

The significance of Jagan Mohan Reddy’s 2019 victory cannot be understated. Previously, he had departed from the Congress government and established his own YSRCP to carry forward the legacy of his father, Y S Rajasekhara Reddy, who tragically lost his life in a helicopter crash in 2009. While the reports of shock-induced deaths and suicides following Rajasekhara Reddy’s passing were not independently verified, Jagan embarked on an ‘Odarpu Yatra’ to offer solace to the families of the deceased supporters, an initiative that garnered widespread political support. In the 2014 state elections, votes swiftly shifted from the Congress to the YSRCP. In the 2019 elections, the Congress secured a mere 1.17 per cent vote share, which was even lower than the 1.28 per cent vote share recorded for NOTA (None of the Above).

Similarly in Telangana, the Bharat Rashtra Samithi (BRS) has been riding on the sentiment for a separate Telangana state. As per the schedule, the state assembly elections will be held in December this year. While the ruling party did suffer some setbacks in the last elections, party leaders are confident that the BRS would secure a third term in the state. The party has already unveiled its roster of candidates for 115 of the 119 assembly seats in the state. But there are concerns within the party that if simultaneous elections are held, the state elections may be deferred to either March or May of the ensuing year to align with the Lok Sabha elections. In this scenario, it would present a formidable challenge for candidates to maintain the momentum of their campaign efforts over such an extended period, compounded by the constraints of resource availability. The BRS is also worried about the prospect of their localised political agendas being eclipsed by the overarching national narratives along with the anti-incumbency factor. This situation may go in favour of either the BJP or the Congress, diminishing the prominence of regional politics within the electoral landscape.

Scholar Venkatesh B Athreya says the concept of ONOE poses a potential threat to the aspirations of linguistic identity, particularly raising concerns about its reception in south India. Athreya emphasises that the objectives and needs within the realm of development vary significantly from one state to another. He elucidates this by citing the example of Kerala, which has made considerable strides in development compared to other states, and Tamil Nadu, which has also achieved noteworthy progress. In the context of elections to the legislative assembly, Athreya underscores that campaign themes and concerns are distinct and region-specific for each state. Moreover, Athreya says that the proposition of simultaneous elections for both Parliament and assemblies carries an underlying intention of supplanting regional political narratives with a broader Hindutva-based discourse.

“If the BJP comes up with slogans such as ONOE, it is going to be fatal for the party in south India,” says Govindan. The CPI(M) has already initiated a campaign against the concept of ONOE. Thomas Isaac, former finance minister of Kerala, posted a note on Facebook debunking the theory that ONOE would lead to cost reduction and save public funds. “The 2019 Parliamentary elections incurred a total expenditure of Rs 8,976 crore, amounting to a mere 0.33 per cent of the overall budget. A substantial portion of this expenditure, approximately 60 per cent, was earmarked for the procurement of voting machines. Holding simultaneous elections would necessitate a doubling of voting machines, polling booths and personnel, inevitably resulting in a significant escalation of costs,” says Isaac.

Isaac emphasises on the variance in election themes—whether for Parliament or for assembly elections—stressing that these are intricately tied to the socio-economic conditions prevailing in different states. For instance, Kerala consistently raises concerns about perceived discrimination in fund allocation. As Kerala’s Finance Minister K N Balagopal points out: “The state receives only 25 paise for every one rupee it contributes in taxes to the Union Government, whereas Tamil Nadu receives 40 paise, and Karnataka 47. In contrast, Uttar Pradesh receives Rs 2.73 and Bihar gets Rs 7.6 for every one rupee.”

Given these significant disparities in fund allocation, tax-sharing arrangements, GST compensation and other incentives among states, it has become evident that the Union Government cannot advocate an ONOE agenda without applying different criteria for different states. The BJP in south Indian states, which are already in a precarious position, would encounter formidable challenges in elucidating and brokering such a policy, potentially limiting their political manoeuvrability.

(This appeared in the print as 'Hostile Reception')

Shahina K K in Thiruvananthapuram and Anisha Reddy in Bengaluru