It was this day 74 years ago when the cartographer's ruthless pen "broke the dreams" of a young girl and many others living in an obscure village in the present-day Bangladesh amid the festive cheer Independence had brought.

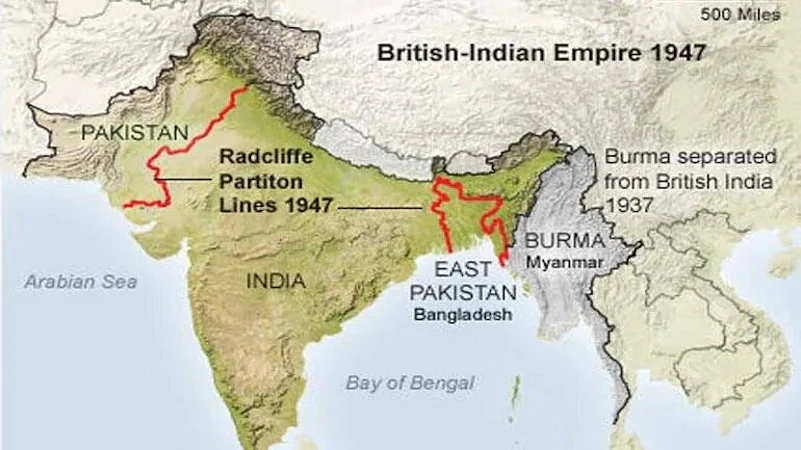

For Tripti Sircar nee Roy Chowdhury the joy of gaining freedom from the British rule on August 15, 1947, ended in shock and dismay three days later when news broke of the Radcliffe award delineating the borders of newly independent India and Pakistan. Her five centuries-old Ulpur village in a Hindu majority area had gone to Pakistan.

Sircar, 89, who now lives in Kolkata, remembers wistfully "how excited our village in Faridpur district of present-day Bangladesh was on the day India made its 'tryst with destiny’… everybody hoisted the tricolour, we distributed sweets and sang patriotic songs".

As night fell on August 17, the award was made public and most Indians, including Sircar and her extended land-owning family, came to know of the momentous news from morning newspapers on August 18.

In Behrampore in Murshidabad district, some 270 km northwest of Ulpur, it was a picture in reverse just days ago on August 14 as Muslim League volunteers proudly marched through the town with a band and Pakistan's star-and-crescent green flag. It was the day when Lord Louis Mountbatten made his farewell speech in Pakistan's new legislature in faraway Karachi.

Three days later, stupefied Muslim League supporters realised Sir Cyril Radcliffe had so wielded his pen that the Muslim majority district had been awarded to India.

The announcement of the Radcliffe award was like a rude "Swapna-Bhanga" (broken dream) for those who had believed that religious demography alone would determine the nation they would live in.

"Unlike Punjab where there was large-scale ethnic cleansing and a full-scale transfer of population in a few months, Bengal, with its unique demography and syncretic and shared culture, saw less bloodshed and refugee transfers were not sudden but staggered over a longer frame of time," former Indian diplomat TCA Raghavan, the author of 'The People Next Door: The Curious History of India Pakistan Relations', told PTI.

Sircar's family travelled by boat and train to Calcutta, almost six months after the partition.

The family of Khan Bahadur Fazle Rabbi Khandokar, the Dewan (finance minister or prime minister) to the Nawabs of Murshidabad, split up with one section choosing to stay on in Murshidabad, while another made its way to Dhaka and yet another to Karachi.

However, whether the journey was made within days of the Radcliffe award or months or years later, the uprooting was as traumatic as it was enormous.

Sugata Bose, noted historian and former Lok Sabha MP at a public lecture on 'The Legacy of Loss' on Tuesday accused Mountbatten of not announcing where the borders lay because he did not want to "interrupt the festivities".

The accusation was not without any basis. Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a London lawyer who knew little of India but had been tasked to head both the boundary commissions to draw up the border in eastern and western India, submitted the award report on Bengal on August 9, while the report on Punjab's borders was submitted later.

According to the voluminous transfer of power documents, Lord Mountbatten immediately afterwards sought his staff's advice on whether it would be desirable to publish it straightaway. The advice seems to have favoured delaying the announcement as the British would be held responsible for the resultant "disturbance".

The attempt to safeguard British interests resulted in hundreds of thousands of innocent people having no clue about where their home and hearth stood after borders had been drawn.

Radcliffe's decisions were based on claims and counter claims by the Congress and the Muslim League. For India, the Congress had claimed fifty-nine per cent of the total area of undivided Bengal despite the fact that Muslims were in a majority in the state. Radcliffe's boundary commission, however, gave West Bengal some 36 per cent of the land.

While the fate of most districts in Bengal was decided on the basis of which community had a majority and whether the areas they lived in were contiguous or not, Radcliffe had to decide which of the successor states would get Calcutta, which both the Muslim League and Congress wanted.

Equally important was the question as to how the river system that was the lifeline of the port city and its trading links with the hinterland was to be carved up.

It also had the onerous task to decide which states should get the borderlands of Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri in the north and Chittagong hill tracts in the east.

However, Calcutta, the crown jewel, was awarded to West Bengal, much to the disappointment of the Muslim League, situated as it was in the Hindu majority 24 Parganas.

In an interview to noted journalist Kuldip Nayar in 1971, Radcliffe revealed he gave Pakistan Lahore as "I had already marked Calcutta" to India.

But more importantly, the Farakka headwaters of the Hooghly, which flowed as Bhagirathi through Murshidabad and Nadia, was given to India along with the districts through which they passed, regardless of the mixed Hindu-Muslim population.

A government memorandum written for the India and Burma Committee of the British cabinet made it clear that these changes are designed to leave to West Bengal control over Calcutta's river system.

Below Calcutta, the Mathabhanga distributory of the Ganges was accepted as the border between the two nations and most of the Hindu majority district of Khulna awarded to Pakistan. The tea growing districts of Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri came to India, save a few blocks which were given to Pakistan.

However, Radcliffe gave the entire Chittagong Hill Tracts, which had an overwhelming Buddhist tribal majority, to Pakistan on the plea that its economic life depended on links to Chittagong port, despite strong protests by interim Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

"What the division and the way the division was handled with delayed announcement did was build a sense of victimhood on both sides of the border," said Rajat Roy, political analyst and member of the Calcutta Research Group.

The immediate political fallout was that the Communist Party, till then a fringe force in Bengal, gained traction as the champion of refugees and managed to wrest 28 seats in the 1951 elections to the West Bengal state assembly, and rose steadily to eventually rule Bengal for an unprecedented 34 years since 1977.

Across the newly defined border, the Muslim League, which so desperately wanted partition, stumbled as Muhammad Ali Jinnah, its founder, made the announcement in Dhaka University in March 1948 that Urdu and not Bengali will be the sole official language of Pakistan, facing protests by students who heckled him, possibly a first for the all-powerful Qaid-i-Azam.

The movement for Bengali language to be recognised as official language snowballed into an emotive upsurge which saw the Awami League being born and demands for greater autonomy for East Bengal being voiced. This new movement that drew support from the Muslim intelligentsia, which relocated to Dhaka from Calcutta, eventually culminated in the war of independence and led to the creation of Bangladesh in 1971.

"We want to remember both the rupture and the continuity of Bengali life… there is continuity in language, literature, food and creativity that we see on both sides of the Radcliffe line," said Rituparna Roy of the Kolkata Partition Museum, a project dedicated to Bengal's partition history.