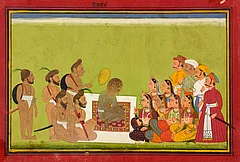

‘Godmen’ talk even when they’re quiet. Sometimes, they don’t even need to talk—they sing, they dance, they perform. Sometimes, they just sit and gold dust falls. Babas are not just the new gods; they’re the new heroes, directors, choreographers: dancing themselves and making others dance.

A few decades ago, such figures usually wore saffron robes, but now they’re more specific, as if fulfilling both a Job Designation (JD) and creating their own brands. Compare this group to the superheroes in The Avengers universe whose ‘JDs’—and costumes—make them unique. Or, like cartel members’ tattoos, godmen’s clothes—sometimes names—signify their essence and sharpen their identities.

Consider Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh Insan, whose Dera Sacha Sauda (DSS) attracted many Dalits to the organisation. They joined it believing a non-Hindu organisation would liberate them from the tyranny of the caste system. And if they still harboured any doubt, then the word “Insan” resolved it all: a place for anyone and everyone. So, when it comes to babas, if the question is ‘what’s in a name?’, then the answer is another question: How about everything?

Colour psychology, too, plays a crucial role. If filmmakers deploy it to elicit emotional responses—most notably evident in Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colours trilogy—then marketing professionals use it to distinguish brands and influence consumers. The spiritual screenwriters, babas, rely on it for similar ends: establishing personas, conveying messages, selling products. They also sell faith, or hope, in a country devoid of a sustained welfare state. When the government receded, creating a void, the babas stepped in, functioning as a protector, therapist, father, doctor, rehab, God. This space is as competitive as ever, compelling godmen to adopt creative means to stand out and build their brands.

As godmen have diversified, so have their hues, but one colour still dominates: white. From Asaram Bapu and Sri Sri Ravi Shankar to Brahma Kumaris and Bhole Baba, white prevails because it symbolises many positive connotations, such as honesty, abstinence, and cleanliness, which most godmen claim as their default qualities. Given that several babas, or groups (like Brahma Kumaris), also obsess over ‘purity’, reflected in their focus on vegetarianism and celibacy, white fits them like a hand in a glove.

As godmen have diversified, so have their hues. but one colour still dominates: white. From Asaram Bapu & Sri Sri Ravi Shankar to Brahma Kumaris & Bhole Baba, white prevails.

Sometimes, white hides. Take the Goa-based Sanatan Sanstha, a hard-line Hindu organisation, whose members have been accused in the murders of Govind Pansare, Narendra Dabholkar, and Gauri Lankesh. According to its critics, the Sanatan Sanstha is as dangerous as it is secretive. Few people have entered its headquarters and fewer know what goes on inside. That secrecy, too, seems to follow a convoluted circular logic, an anti-PR campaign that functions as a PR campaign: You can only know what we want you to know. Yet, even one look at its founder, Jayant Athavale, will confound you as, often dressed in white and looking serene, he cuts the figure of an amiable old man, as saatvik as they come, projecting a ‘pure’ persona. The contradictions continue to pile up: a doctor-founder and irrational teachings, the fixation on Ram Rajya and the accusations of hypnosis.

Not all godmen are godmen though. Some are ‘godwoman’, like Radhe Maa, whose devotional vocabulary contradicts her male counterparts’. Like most babas, Maa is melodramatic, but she’s less Prithvi Theatre, more Bollywood. Based in Mumbai, she puts the bling in blessing, dancing to Hindi film songs, appearing in Bigg Boss, wearing mini-skirts. More ‘colourful’ than most babas, she elicits devotion and desire; her clothes complementing her brand: sarees drenched in red.

Some godmen’s attire conveys their ideologies. Consider Nithyananda who—claiming to establish a Hindu rashtra on a South American island—used to wear saffron robes (and its variants) in his satsangs. Before he fled the country evading charges of rape and abduction, he had styled himself as a ‘neoliberal baba’ , underscoring both spirituality and pursuit of personal wealth. No wonder, then, that he surrounded himself with appropriate opulence: sitting on a golden throne, wearing golden chains, sporting a golden ring on every finger. Celebrating wealth in the ‘new India’ further, Google Golden Baba, in Kanpur, dresses entirely in—what else but—gold. (During COVID-19, he wore a gold-plated mask.)

Baba Ramdev, in contrast, appears bare-chested in his yoga sessions. This, too, makes sense because, for Ramdev, his body is his product: the different ways in which he bends, contorts, and rotates it, demonstrating expertise and inspiring faith. And when he’s not half-naked, he’s dressed in saffron, as his business model rests on rejecting the West and offering homegrown alternatives—even peddling Coronil as a cure for COVID-19—that finds a natural ally in Hindutva.

If Ramdev is minimalist, then the DSS chief is maximalist. Just look at his name (again!)—Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh Insan, which references three religions—and his colours and clothes, which subvert conventional dress codes. Before his arrest, Insan’s “modern urban lingo—rock star, bling, dude, etc.—emphasised his ‘being at home’ in India post-liberalisation,” write Jacob Copeman and Koonal Duggal in Gurus and Media (2023), “seeking to attract millennials [who would eventually refrain from consuming drugs].”

His ‘maximalism’ hammered such overpowering visuals that they approximated omnipresence—the guru was so all over the place that he could never not be present. This omnipresence, signalling presence even in absence, took literal forms in Nithyananda’s case where, after absconding from the authorities, his team continued to flood social media platforms with his images, messages, and satsangs. The guru, after all, never left; he merely changed forms: from analogue to digital. Likewise, Ramdev used television in the early aughts, via Sanskar and Aastha TV, to catapult to stardom.

Some godmen’s attire conveys their ideologies. Consider Nithyananda who—claiming to establish a Hindu rashtra on a South American island—used to wear saffron robes.

Unlike most godmen, Insan used cinema to bolster his brand, helming five projects from 2015 to 2017, where he served as a director, screenwriter, singer, choreographer, music director, art director, casting director, production designer, costume designer, sound designer, and on and on, and on and on, hogging up to 30 credits—a world record. Baba-ji wasn’t just making cinema; he was cinema himself.

This complemented his off-screen image, for his website characterised him as a “Spiritual Saint, Writer, Director, Scientist, Feminist, Youth Icon”. Or, in other words, he had become an ‘all-in-one’ baba. “‘All-in-one’ phraseology is, of course, inspired by commodity labelling and advertisements,” write Copeman and Duggal, “and its use to describe the DSS guru is more than an analogy: ‘all in one’ is indeed his marketing strategy.”

The MSG franchise takes it to a whole new level, packing superhero spectacles, stardom, omnipresence, omnipotence, mythmaking, brand-building, and, of course, Narendra Modi and his politics. If Rajinikanth’s films turn an actor into a God, then Insan’s movies invert that paradigm: finding an actor in God. The MSG dramas are suffused with superhero imagery, which makes perfect sense, as these godmen see themselves—and are seen—as superheroes. The poster of MSG: Messenger of God (2015) features the brawny baba standing on a rock, literally towering over his devotees, not too different from another saviour, Batman, surveying Gotham City from a skyscraper. The parallels continue throughout the film with striking additions: Baba stops the bullets [like Keanu Reeves in The Matrix (1999)], then turns them into a tiara gracing his head; he flies like Superman and, embodying the Love Charger song, makes swords flowers. His movies also doubled up as outreach programmes, which, riding on VFX-powered ‘miracles’, hoped to find newer audiences via dubbed versions in Tamil, Telugu, and Malayalam.

Supporting Modi in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, Insan sought to unite the two cults. In MSG: Messenger of God, “the guru turns other characters” to look like him, which recalls the “Modi mask-wearing phenomenon”, add Copeman and Duggal, “demonstrating the reduction of everything to the guru” —a totalisation that marks “DSS guruship” as well.

In the sequel, he reforms the Adivasis—or, according to a dialogue, “humanises the devils”—by becoming their “Adi Guru”. He also claims the Rajput lineage in the same drama by referencing the medieval king Maharana Pratap, “portraying himself as an upper-caste saviour”. More crucially, Pratap had died fighting Muslim rulers, making him a hero of the Hindu right. Insan’s character takes it forward by becoming a gau rakshak.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

His next films echoed the BJP’s politics even more. Inspired by the 2016 Uri attack, Hind Ka Napak Ko Jawab (2016) has Insan playing Sher-e-Hind who unleashes a “surgical strike” on aliens, who have landed in Pakistan disguised as jihadis. The drama vilifies the Pakistani army (shorthand for Muslims), while extolling Modi and deriding the Opposition. In Jattu Engineer (2017), he plays a schoolteacher who transforms a village, Tatiya Kar (literally meaning To Shit), that lacks proper sewage, governance, and a school. Here, too, he plays an upper-caste saviour, showing Modi in a favourable light (through Swachh Bharat Abhiyan). Godman meets superhero meets Prime Minister completes a baba’s ultimate dream: not a messenger of God but a messenger of Modi.

(This appeared in the print as 'How 'Baba'nomics Works')