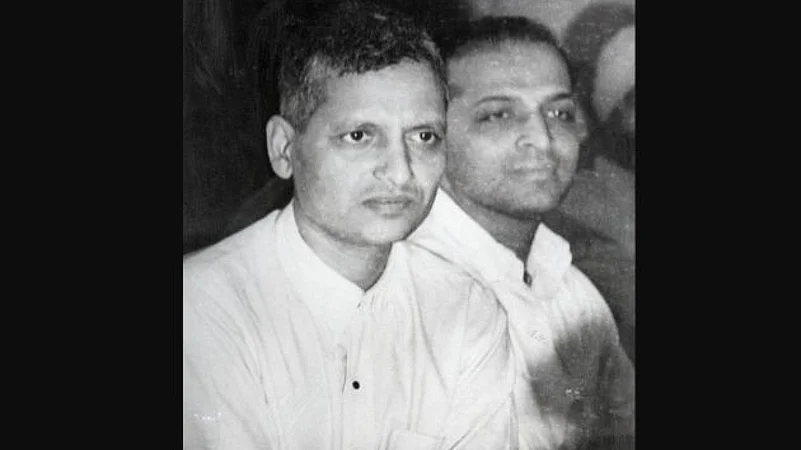

The idea that Godse would assassinate Gandhi was conceived during the sleepless night of 23 January 1948.

It is, however, not entirely understood whether Godse came up with the idea or Apte made him express his readiness to do the job. After they arrived in Bombay from Kanpur late that evening, they booked a room at Arya Pathik Ashram. They put their luggage in the room and went out. Till late that night, the pair stayed out on the streets of Bombay, discussing and agonizing over the prospects and implications as they groped in the dark for a new sense of direction. Even when they returned to their room, the discussion continued and they hardly found time to sleep.

Their agony did not go unnoticed. Gaya Prasad, the manager of the lodge, observed their restlessness with curiosity. ‘On 23-1-48, Apte came at 9 p.m. with another man,’ he said later. ‘They went out and returned at 1 a.m. and spoke until 3 a.m. They kept the light [of the room] on till then.’ Early the next morning, they walked out again; Gaya Prasad remained clueless about the identity of the man who accompanied Apte. According to him, ‘On 24-1-48 Apte and another man left the hotel at 6.30 a.m. I asked Apte to give me his companions name. He failed to do so.’

By then, their lengthy conversations were over, and they had come out of their paralysed state and taken a fresh decision: they would no longer depend on a ‘third person’ to shoot Gandhi. ‘Instead of looking for a third person, I decided to go personally in front of Gandhi and empty the pistol in him,’ Godse said later. ‘It was also decided that Apte and Karkare would come along only to provide support to me.’

How long had Godse harboured this thought has remained a mystery. Since he started hating Gandhi for obstructing the Hindu Rashtra project and seeing Gandhi’s assassination as an act of, in his mind, masculine valour? Or since his return from Delhi, when the failure of an elaborate assassination plan pushed him to act himself? No one can say with confidence because in public Godse never said anything more than the political rhetoric of a typical tenor.

Godse’s change of heart seems to have been given impetus during his day-long stay at Kanpur railway station following the failed assassination attempt. ‘There we heard so many people expressing disappointment over the failure of the attempt to kill Gandhi,’ he said later. ‘Most of them held Gandhi responsible for the killing of Hindus in Pakistan and wished that he should have been killed in the bomb attack. This kind of response made me believe that we were on the right track.’

The responses he heard in Kanpur might well have prompted him to take the risk. There was an obvious danger to his performing that role; the chances of it being a suicide mission were high. Yet Godse opted for it, hoping perhaps that he would be hailed by the larger public, especially Hindu and Sikh refugees. In fact, he seemed to believe that the popular reaction aroused by the murder of Gandhi would make him a hero and shield him from the gallows. As always, when he recounted the decisive situations in his life, Godse spoke of the strain of the decision and emphasized the ‘hard’ mental effort it cost him.‘For three days I had lengthy and reflective conversations with Apte before I came to the conclusion that I had to take this step. There was no option but to kill Gandhiji,’ he said.

In any case, once the decision was taken, Godse and Apte moved fast. Haunted by the fear of the police, they had to, therefore, remain virtually invisible until the job was done. The fear was real, for Pahwa, during the interrogation, had named ‘Karkara Seth’ of Ahmednagar and talked about the ‘editor and publisher of Hindu Rashtra’ of Poona and the ‘editor’s younger brother’ as his accomplices. He had also told the interrogators about the involvement of ‘a bearded weapons supplier’ and his servant.7 Though he had not specifically mentioned the names of anyone other than Karkare, the leads he had provided were enough to immediately identify all the conspirators.

As the threat of the police loomed largely, Apte, once again assuming charge, showed great presence of mind. First, he shifted Godse to a new hotel —Elphinstone Hotel at CarnacBunder — during the early hours of 24 January. ‘Nathuram engaged a room in the Elphinstone hotel and resided there,’ Apte revealed later. Then, apparently, to remove the suspicion of the manager of Arya Pathik Ashram about Godse and to give him the impression that he remained the same old self, Apte returned with Manorama at 11 a.m. and remained locked up with her in his room for more than two hours.

Having managed the affairs in Bombay, Apte set out to prepare the ground for a fresh attack on Gandhi, while still retaining the room in Arya Pathik Ashram for the day. The most important issue at this stage was to arrange a weapon. Apte accordingly turned to Gopal, who had returned to Kirkee from Delhi with two revolvers and a hand grenade. ‘At 9 p.m. on 24-1-48 Apte came to my residence at Kirkee,’ recounted Gopal. ‘He questioned me whether I was still in possession of the revolvers and the hand grenade. I told him that the stuff was with me. He then asked me to accompany him to Bombay by the night train and to bring along with me the hand grenade and the small revolver. I agreed as the next day was a Sunday.’

Shortly before noon on 25 January, the three met Elphinstone Hotel, where Gopal handed over the weapons to Godse. Gopal then departed but he was apparently not informed that Godse would personally assassinate Gandhi this time. Around 10 p.m., Godse and Apte revealed their plan to Karkare. ‘Godse was in a supreme mood,’ Karkare recounted. ‘He [. . .] suggested that we should not have nine or ten persons in our clique as history showed that such revolutionary plots where several persons were concerned had turned futile and it was only the individual effort that would succeed. He gave me several examples from the history and told us that acts of individual persons as by Madanlal Dhingra and Vasudevrao Gogate [Vasudev Balwant Gogate] had proved successful because they were individual efforts and therefore he individually had decided to assassinate Gandhiji.’

The conversation, which took place at a relatively quiet corner of a moonlit railway station platform in Thane, shows that Godse conceived his decision to kill Gandhi as an echo of ‘revolutionary acts’ of two Savarkar loyalists. ‘I was stunned and I found Apte was keeping quiet. I thought that Godse and Apte might have already discussed this and Apte was aware of Godse’s decision,’ Karkare said. ‘I told Godse that I was prepared for the worst and would join them in this mission.’

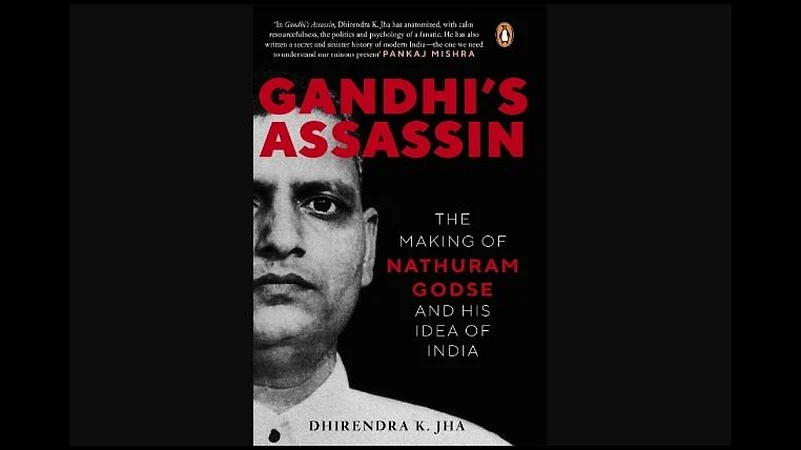

(Excerpted from Gandhi’s Assassin: The Making of Nathuram Godse and His Idea of India By Dhirendra K. Jha (Penguin Random House India)

(Dhirendra K. Jha is a Delhi-based journalist. He is the author of Shadow Armies: Fringe Organizations and Foot Soldiers of Hindutva; and Ascetic Games: Sadhus, Akharas and the Making of the Hindu Vote. He is the co-author of Ayodhya The Dark Night: The Secret History of Rama’s Appearance in Babri Masjid. The views expressed in this article are personal and may not necessarily reflect the views of Outlook Magazine)