In 1983, a divorced, single mother from a wealthy and influential family in Kerala, sued her brother for a fair share in the ancestral property of her father, a former Imperial Entomologist at the British court, who had died intestate. At the time, women of the deeply-conservative and close-knit Syrian Malabar Nasrani community were not entitled to inherit their fathers’ property, under the Travancore Christian Succession Act of 1916. In 1986, however, Mary Roy won the lawsuit against her brother George, marking a landmark shift towards gender justice, not only for Christians but for all Indian women. Years later in 2006, Roy, who had by then become an educationist, women’s rights activist and ‘Ammu’, the protagonist of her daughter Arundhati Roy’s Booker-winning The God of Small Things, told a researcher that she did not do it for “public good”. She did it because she was just “so angry”.

Much has happened since 1986 when it comes to women’s land rights. The Hindu Succession Act 1956 and its 2005 amendment, gave daughters the right to own and inherit ancestral property. In later verdicts, the Supreme Court (SC)upheld that the Act was applicable to women born before 2005 and also to those whose fathers died before 2005. Inheritance rights of widows have also been strengthened since 1937 when it was first introduced.

But much like Roy, women in India remain angry.

While Roy was an upper-caste woman born into a wealthy family with a lot of ancestral property (her share amounted to Rs 2 crore, which she later donated to charity), land rights in India mostly affect women from lower social and economic strata. When it comes to the most marginalised sections, successive SC judgments and legislation have failed to truly address the real problems.

Legal and technical gaps

Since succession, inheritance laws and the processes vary from state to state and community to community. Let us take the case of one state, Gujarat, where, despite the Hindu Succession Act, women in both urban and rural areas find it harder to inherit ancestral land.

One of the first problems is the lack of legal and digital literacy regarding succession/inheritance rights and laws. Neelam Patel, a lawyer who works with the Working Group For Women And Land Ownership (WGWLO), a consortium of groups working for land rights of women farmers in Gujarat, says awareness about land rights and about the various documents and processes required to even get their names registered in the property mutation papers, remains largely absent. WGWLO is a network of CBOs, NGOs and individual members working on awareness, action (paralegal cadre training and process support), research and advocacy-oriented holistic work to strengthen the women's land rights movement work from grassroots to policy level.

“We have been working in Gujarat since 2002, to build identities and rights of women engaged in agrarian work. We find large gaps in awareness and implementation of succession laws and processes,” Patel, land rights advocate working with WGWLO, tells Outlook.

The process of filing for succession is tedious, and requires a woman to not only prove that her father/husband/brother is dead (meaning a death certificate that women often don’t possess), but also to procure two witnesses who know her and can vouch for her as related to the deceased. These witnesses, Patel states, are usually susceptible to pressures and bribes from the woman’s male family members or in-laws who might be trying to edge her out of the inheritance.

Even after a woman manages to collect all necessary documents and reaches a patwari (junior revenue official) with the witnesses to get her name registered for the mutation and succession papers, in-laws or relatives of the woman often get it removed in subsequent documents through bribery, forgery or deceit.

“In cases of dispute, the onus to prove ownership of the property is usually on the woman. If there are others staking claim to the property, it becomes the woman’s job to collect each of their signatures and Aadhaar details and submit them to the patwari. Many refuse to willfully give their details to delay or hinder the succession application,” says Ashwinbhai Gamit, a community-level para-legal worker (PLW) trained by the consortium to help women facing property dispute cases in rural Gujarat.

Ashwinbhai, who is part of a network of PLWs working on ground to increase technical and legal literacy among women, states that lack of steady internet services or smartphone access in remote rural regions, also hinders the online application process. He adds that in villages, patwaris illegally charge anywhere between Rs 5,000-30,000 just to get these simple documents made or approved.

Lifelong stigma

Social stigma related to widows and unmarried women also percolates down to the implementation of succession laws. “After a husband’s death, a widow’s in-laws use various tactics to remove her from the property, from fear of her remarrying and leaving with her share of it,” says Parulben Harhadbhai Kolipatel, another PLW from Ahmedabad district. She adds that these acts find overall support from the community.

Such stigma can even take the shape of violence. In tribal areas, the work of paralegals includes campaigning against social ills like the dayan pratha (witchcraft), which continues to be prevalent in Gujarat and states like Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. Adivasi Jan Adhikar Manch activist Aloka Kujur from Ranchi had previously spoken to Outlook about how the dayan pratha was frequently used as an excuse in Jharkhand to threaten or kill landed single or elderly women and usurp their property.

Community workers like Parulben who work with widows or socially sensitive cases like inter-caste marriage leading to property disputes, may themselves face threats from families of the women they represent. “I have faced such threats from disgruntled in-laws, asking me to stay away from a case. It’s a problem women paralegals commonly face. We try to help out other women as much as we can. But ultimately, it’s the State’s job to provide safety and support. We can only do so much at the community level,” she adds.

Generational inequalities

Polygamy among some tribal groups like the Gamits, who are also governed by the Hindu Succession Act and form a sizeable chunk of Gujarat’s population, is another interesting example of the many complexities that land rights activists face when implementing SC orders on succession and inheritance.

Radhaben, who belongs to the Gamit community in Gujarat and has been fighting for rights to her ancestral agricultural land since 2020, brings up an interesting question. Her great-grandfather had two wives. Her grandfather, son of the first wife, also had two wives. Her father was the son of the second.

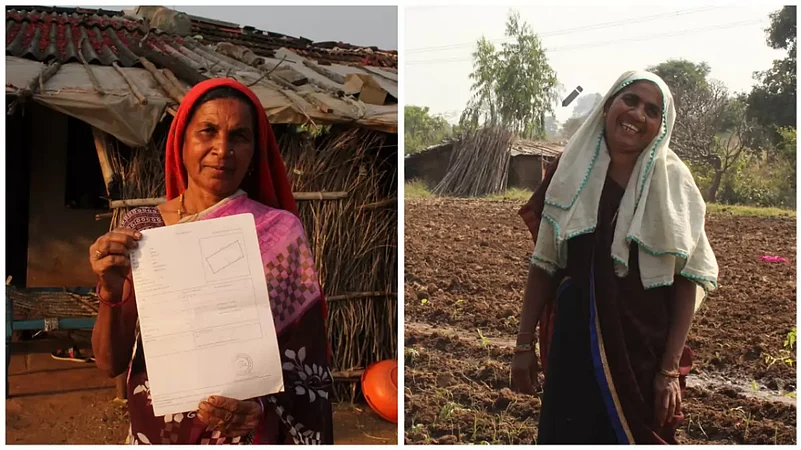

Now, after the death of the great-grandfather in 2018 and her father in 2020, who had no male heirs and died intestate, Radhaben and her two sisters are being asked to vacate their great-grandfather’s land. In such cases, the claimant has to first prove the family tree, which requires Radhaben to procure documents that date back three generations. She also has to seek consent and submit documents for each of the 48 family members who are contesting claims to the land, just to get her name on the papers. Radhaben and her sisters are not literate and depend on the farm for survival.

“Back in those days, land was bequeathed by elders orally. My mother and my sisters’ names were not there in the property or varsai (inheritance) papers. We have no brothers, so other relatives have all joined hands against us as we are women and they think we’ll give up soon,” she tells Outlook.

Since the Hindu Marriage Act rules out polygamy, laws related to the property rights of the first and second wives and their progeny are highly nuanced, and require the judge to invoke multiple Acts in order to arrive at a justifiable verdict.

In India, laws governing property ownership, succession and inheritance are rooted in inequality and an oppressive caste system. If upper-caste women get the raw end of a property deal vis-a-vis their brothers, those from the oppressed castes have no rights to property at all. The Manusmriti and other ancient Hindu legal treatises, which laid down these retrogressive rules for property ownership, mentioned that the property of upper-caste women who marry outside caste or to lower-caste men, would not be passed on to the lower-caste family, but to her own paternal bloodline, thus keeping the property within the caste group.

Incidentally, the Manusmriti continues to echo today. Some 400 castes across Gujarat have recently demanded that the government lawfully deem that if any daughter marries outside her caste according to her wish, she should not legally inherit any parental property.

Among Dalit families, the question of succession and inheritance rights on private property is almost immaterial, as a majority of Scheduled Castes in rural India continue to be landless, with barely any private property to fight over. And when they do, surveys show that Dalit women find it harder to access legal or social resources due to lack of financial stability, social standing and caste discrimination. Critics of India’s “progressive” gender justice movement have noted that reforms in land laws, much like other gender-related reforms, have failed to truly account for women from the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

The work done by NGOs and advocacy groups like WGWLO has led to a positive change in Gujarat, where the practice of adding a woman’s name to land records and documents while the father/husband/brother is still alive, and not after their death, has been implemented. “The ultimate goal is to make land and property ownership more accessible to women, and to strengthen the identity of women farmers. Why wait for the male relative’s death to give women some agency? Transferring land rights to women while the male relative is still alive, helps build financial agency and independence among women right from the beginning,” says WGWLO communications officer Megha. However, change has been slow. The process requires consent from the girls’ in-laws and families. Megha says most husbands and in-laws refuse immediately.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Such a Long Journey" in September 2022)