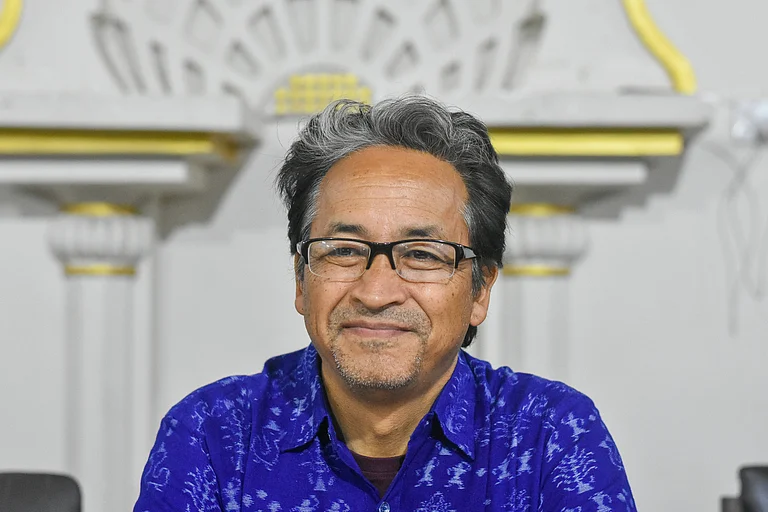

Hem Mishra was a graduate student at Jawaharlal Nehru University when he was first arrested in 2013 from Maharashtra's Chandrapur district. He was accused of working as a messenger for the proscribed outfit CPI Maoist and charged with waging war against the country. On March 7, 2017, Hem and five other persons were sentenced to life imprisonment by the Gadchiroli sessions court. On March 5, 2024, the Nagpur bench of the Bombay High Court acquitted Hem and five other accused in the case. After his release Mishra talked to Outlook’s Vikram Raj about his imprisonment, trial and experiences.

Under what circumstances were you arrested?

I do not call it an arrest. I was abducted. This happened in August 2013. At that time, I went from Delhi to meet Dr Prakash Amte, who was working on the health issues of tribals in tribal areas. I was curious to understand the difficult circumstances under which he worked.

On the 19th, I left from Delhi, and around 10 am on the 20th, at the Balharshah station in Chandrapur district, I was coming out of the station, planning to take a bus to Hemalkasa where Prakash Amte's hospital is located. Suddenly, a few people in civil clothes abducted me. I couldn't understand why this was happening as I had no enmity with anyone here.

Shortly afterwards, they put me in a van. For 3 days, I was kept in illegal custody at different places. They blindfolded me and took me from one place to another, not allowing me to sleep. I was tortured, and on 23rd August 2013, I was produced in court in Aheri.

What was the reason behind your arrest, in your opinion?

I am from Uttarakhand. When the movement for a separate state based on equality was going on in Uttarakhand, it had an impact on the students and youth there. When I came to the JNU campus, Uttarakhand had become a state, but issues about what kind of state we should demand persisted . This movement influenced me. Cultural poets like Girish Tiwari 'Girda' were part of the Uttarakhand Movement. His songs reflected the lack of education, water scarcity, and displacement in remote Uttarakhand villages. There was a big development issue - no roads or employment opportunities in the hills, forcing a member from almost every family to live in Delhi, often doing menial jobs under difficult conditions. Girda's songs captured the suffering of the people, which impacted me.

So, I joined this movement through a student and cultural organization. We tried to make students aware of the repressive policies of the government - fake cases being slapped against students, workers, farmers to put them in jails. We campaigned against such policies of any ruling power.

When I joined JNU in 2010, I participated in various movements here too, as JNU is known for students' struggles for freedom of expression, democratic rights, and social justice issues of the oppressed sections. Different organizations used to register their protest and demand justice on these issues. As a cultural activist, I participated in many such movements for social justice, raising my voice against wrongful arrests. This background led to my arrest.

Can you reflect on the emotional and mental toll of facing allegations and imprisonment for alleged links with a banned outfit?

The charges levelled against me are completely wrong. Initially, I was accused of being a messenger for a banned outfit. But whose message was I propagating? Through my songs and dafli (tambourine), I could only spread the message of the suffering of the people, to raise awareness among them. If spreading this message is not unconstitutional in this country, then I have always felt that I was wrongly implicated. After a long struggle, I always hoped I will get justice eventually and be released.

It is the misfortune of our generation that the media, social media, big companies, and the powers that be, show dreams of becoming consumers - of cars, bungalows, etc – to the youth. But what is the reality? We talk about a developed India, but it must provide free rations for years to crores of people because they can't purchase essentials. This is the real picture of a developed India.

How did the prison experience shape your perspective on human rights and justice?

Look, when you are in jail, you get time to think about various issues and the value of even small things that we take for granted outside. For example, if you need a pen, you must apply for it, get the jailer's signature - and follow the whole procedure. You must crave even basic things, realizing the lack of human rights there.

When we look at the outside situation from inside the jail, like the space for student movements on the campuses where we studied - at least we could hold protests and rallies. But now that space is shrinking as the government responds with crackdowns. A particular ideology is being promoted while the space for dissenting views and rights is diminishing. Those speaking for human rights are also constantly oppressed and jailed.

The space in which people fought for justice is reducing. The kind of charges we faced earlier are now being extended to the opposition too. The scope of allegations has widened.

How would you describe the role of political ideologies in shaping legal decisions in your case?

I say that there is a need for a strong judicial system in countries like India today. The judiciary of this country, including the Chief Justices, has repeatedly emphasized the need to avoid delays in delivering justice and that bail should be the norm, not jail. However, this is not happening in practice.

If you look at our case, there is no such activity that we are accused of. Our case is completely based on lies. Still, we had to spend more than 10-11 years in jail. In this way, a fear psychosis is created in the media and public. An atmosphere of terror is built, and a system of pressure tactics is employed.

Those who are in the judiciary should not be influenced by this. But attempts are made to create such an atmosphere.

What are your views on the use of violence in pursuit of social justice?

My point is that I was trying to reach out to people with my views through democratic means - protests, which is a right given to us in our democratic system. However, the prevailing social and economic conditions in the country and world are also products of the existing system.

As for the (violent) movements you are referring to, they arise from specific social and economic circumstances and have their own historical backgrounds. The reasons behind them cannot be stopped just by our thinking or that of others. Until we have a democratic system based on equality rather than inequality, and move effectively towards an egalitarian system, such phenomena will persist in society.

What are your plans and aspirations, both professionally and personally, after the acquittal?

When I came to a premier institute like Jawaharlal Nehru University, I had the dream of pursuing my studies. Now, after more than 10 years, academically as well as personally, I would say it has been a big loss. I have just been released, and 10 years is a long time. I will have to think about which direction I should take for my future.

What message would you like to convey to individuals enduring similar circumstances and legal battles?

For them, the message is that in this whole legal system and justice system, there are still people who favour justice. But on the scale that we call ourselves the world's largest democracy, the justice system still has a long way to go to achieve that status.

In such a situation, I feel people will have to live on their willpower and continue the struggle for justice, even in jails. When I was sentenced, I knew I might have to stay in jail for a very long time, despite not having committed that should be considered a crime in a democracy.

My faith in the justice system remains because there are still people who believe in justice. It may be delayed, but it will come. However, 10 years is a long time that cannot be compensated. My release after 10 years feels incomplete because in our case, one tribal undertrial passed away due to lack of medical facilities in jail. The system is responsible for that.

From inside, I feel that while we have been released into a larger space from the 10x10 cell, physically it is a freedom, but not mentally, as some of those who were fighting our case or helping us are still in jail. Professors are jailed. Even those called 'criminals' are a product of socio-economic circumstances, not born so, but forced into it by the system. They too are in jails because of this socio-economic system.

So, without them, my personal freedom does not feel complete. But having come out and meeting you all and my family, friends, is a relief.