Bhaskar Chakraborty was still in his mother’s womb when his parents and family were forced to give up their home and adjoining ‘pukur’ (pond) in Howrah’s Shibpur area in June 1980. Today, Bhaskar is 42-years-old and even though he never saw that old house, Bhaskar feels he still lives there. The smell of moss that is inherent to buildings that co-exist with water bodies seeps through his dry and dingy flat in the HIT quarter, where his and countless other families were “rehabilitated” in the 80s after their homes were broken down to make way for development. Today, the Second Hoogly Bridge or Vidyasagar Setu stands where Bhaskar’s home was. Inaugurated in 1992, the flyover is one of the most popularly used routes that connect the township to the ‘Mahanagar’ Kolkata across the river. For Bhaskar, however, the flyover is more than just a brick and mortar road between two places. It is a bridge between his past and his present and a constant reminder of the high cost, both physical and emotional, of development. And the reason why he chooses to fight on to defend pieces of his childhood that still remain. “I could not save my home then. But I will not let anyone take away another part of my identity,” he says, pointing at the sprawling park beside him in the heart of Howrah.

Bhaskar is one of a group of local residents, advocates, environmentalists and activists from Howrah and nearby areas who have come together to save “Dumurjola Math”, a tree-lined plot of nearly 60 acres of land surrounded by ponds and slopes that have for years been used as a free playground and source of fresh air by locals. But now, the Trinamool Congress government has decided to build a sports city called “Khel Nagari” over the plot and many like Bhaskar are concerned about the cost of building such a commercial hub in the only green patch left in Howrah. The movement to save Dumurjola, the “lungs of Howrah” began around August last year. While the protests made noise, Bhaskar feels it’s nothing compared to the grating of the JCB machines and rock breakers that were now strewn across what once were lakes and parts of the park. “They have already started construction and yet locals have no idea what kind of sports complex they are creating. How many buildings will there be? Will it be accessible to locals free of cost? Can we still take morning walks here? Will the trees be cut down?,” a visibly agitated Bhaskar asks. “They have not told us anything.”

While losing a beloved public spot and one of the only local green patches is concerning on its own, Bhaskar also fears that much like the Hoogly Bridge construction, Khel Nagari too will swallow up a lot of people’s homes and memories.

A complicated history

Dumurjola Math used to belong to farmers and locals in the 50s when the Howrah Improvement Trust came up in 1957 and eventually acquired the fertile land from the farmers at throwaway prices. By 1965, the area was cordoned off with and work began on beautification of the land. In August 1966, HIT announced the construction of a sporting complex in the area. Again, work began, this time for building the projected sports complex. This was also the time when the math became a hub of local football with several star players of the time frequenting the spot for practice under footballer Ashok Kumar Nag. A district football league was also initiated. But the ill-located Dumurjola Math with its potholes and dark forest patches was a turn off to many. In the 70s, the Dumurjola became a hub for Naxalites. Many turned up in the guise of playing football by day and then made bombs at night. But football finally won over. By 1984, however, came news that the field will now be converted into a housing complex to accommodate the families rehabilitated for the construction of Vidyasagar Setu.

At the time, footballer Shailen Manna and Ashok Kumar Nag had opposed the move. A movement ensued and the park remained. In 1992, the CPI(M) government decided to give the field a makeover with a football ground, cricket stadium, indoor swimming pool and other amenities. What materialised was a small stadium and swimming pool behind it which is not in much use today. Then again in 2006, the government tried to develop the area but couldn’t due to local protests. When the TMC came over, the government initiated a plan to convert the land into ‘Khel City’ - a project that encompasses multiple buildings including commercial sports stadiums with viewing galleries, outdoor and indoor sports facilities and accommodation options for sportspersons and players, among other things. The project was initially reported in media in 2018 after it was handed over to HIDCO but work on the site remained stalled for some time. In August 2021, Times of India reported that HIDCO had initiated the process to engage an architectural consultancy and other agencies to carry out the development work on the land.

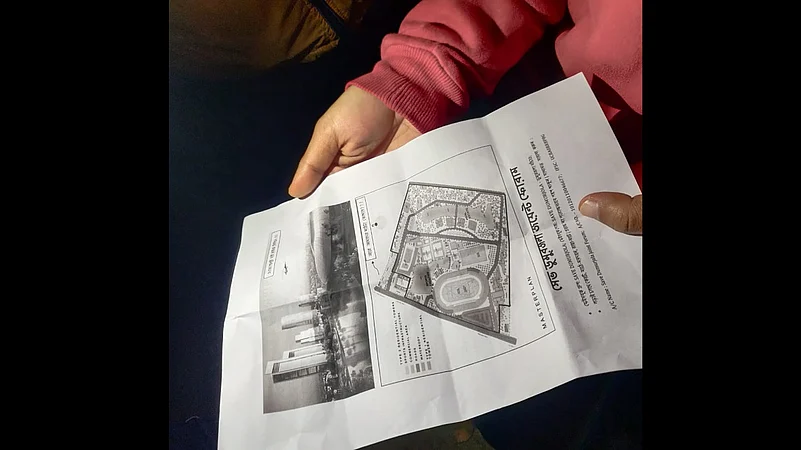

According to the activists, however, plans for the construction of Khel Nagari go as far back as 2015 when an initial version of the RFP for the project was shared on HIDCO’s official website. The listing has since disappeared from the website but photos maintained by Bhaskar show that the initial plan included residential complexes among other things. As per the RFP, only 25 per cent of the 60 acre area would be dedicated to sports.Activists also claim that if the original plan was followed, as many as 400 trees in Dumurjola stand to get cut.

“In the name of creating a sports complex, they are planning to create a concrete jungle and cut off the lungs of Howrah,” says Calcutta High Court advocate Imtiaz Ahmad. In January, the nature enthusiast filed a PIL seeking clarifications of the environmental clearances and plans of HIDCO and the state government. “They are closing up ponds. They are cutting down trees. What do they want to do with that land? As citizens of Howrah, we have a right to ask the government about the way our tax money is being used in the name of development”.

One of the main bones of contention is the lack of any clarity or project plan for Khel Nagari project that is available to the public. What kind of environmental clearances does it have? How much local displacement of local residents will it cause? Ahmad has filed RTIs asking for clarifications but has got no answer. Based on his petition, the Calcutta HC has given directives to both HIDCO and the state government to produce a project plan.

The loss of memories

Back outside the boundary of Dumurjola, the project has already started changing lives. Sudip, who runs a tea shop from where he serves up his father’s famous ‘lebu cha’ (lemon tea) to crowds of young boys flooding the park area in the evening, has been asked to move his shop to another part of town. Sudip claims that his father opened a tea stall here even before Dumurjola Park was built. “We have been here since 1965. My father planted some of these trees. Now they are asking us to move,” he tells Outlook. The other day, he saw one of the trees his father had planted being crushed by a crane. A sharp pain shot up inside his chest. “This place is part of who we are. By turning it into a commercial complex, they may earn some money. But a lot of us will lose our memories. And incomes,” Sudip says.

62-year-old environmental crusader Asit Mukherjee took a bus from Hoogly to Dumurjola on January 1 along with two 6-8 feet tall trees in bags. The trees were then planted at a roadside spot in Dumurjola math - the side facing Sudip’s tea store. “I don’t believe in planting saplings. We need to plant big trees so that they can soon grow bigger and populate the landscape quickly. It’s the only way we can match up to the pace of climate change,” Mukherjee says. However, unbeknownst to the environmentalist, the two trees have met the same fate as the tree planted by Sudip's father.

Pointing at the empty patch where the trees had been planted, Howrah resident and Fridays for Future member Shubho says that trees were uprooted just last week. Shubho has been coming to field ever since he was young enough to venture out to play. Among the cover of these trees, Shubho has hit his first six in cricket, smoked his first cigarette, written his first love letter. The local resident feels that destroying the green cover might end up not just destroying the ecological balance of the area but also act as the end of an era of nostalgia. Furthermore, it’s a travesty of development.

“Dumurjola is not just a park but an ecosystem,” says Shubho says. Every year during winters, hosts of rare migratory birds such as the Amur Falcon, Taiga Flycatcher, Booted Eagle make a stoppage at the waterbodies of Dumurjola. It is also home to a host of native birds including the White Breasted Kingfisher, West Bengal which is dwindling in numbers but found abundantly in this area.

Khel City is being promoted as a way to promote local infrastructure and sports. But Sukrit, a member associated with the movement to save Dumurjola says that the sports city will also obstruct common people from accessing public spaces that should technically be free.

“You have to understand that by creating a commercial sports hub, they will not actually be promoting local talent. The new establishment will likely be accessible at a fee. So locals will then have to pay a fee to enter and play in a park that they had always used anyway for free. Most of the local residents here come from working-class or middle-class background. How many people here would be able to afford that?”

Howrah MP Prasun Banerjee is a celebrated former footballer and has himself frequented the field in his heydays in the 70s. When Outlook contacted him for comment, we were told that the TMC leader is in Goa for the assembly elections and will not be able to attend to the queries.

No answers

As the sun sets on the dug up fields and shrivelling trees of Dumurjola, the members of the Save Dumurjola movement seem overcome by gloomy foreboding. White sand has been poured over patches of land that kids were playing on just last week. The activists allege that the trees are being poisoned so that they die off on their own, making it easier for the government to cut them off. Five protesters have already been booked by police once under the DM Act and the Disasters Act for violating Covid-19 protocols and later released from custody on bail. The activists allege that they were booked under false cases. A woman associated with the movement has alleged harassment at hands of unknown goons. The activists also claim that their posters have been torn. Police and local administration has remained unresponsive, claims Sukrit.

Of what was once a sprawling green respite for a city where the average AQI remains well over the acceptable standard along the year, just patches remain. One of the fields has already been converted into a helipad. Locals question the pointo f creating a helipad in the middle of a sports complex. Many have now started taking to the streets against this imposed "unnayan" (development). They have formed human chains and led protest marches. They have conducted tree plantation campaigns and appealed to media for help. But all of it seems to be falling on deaf ears.

“All we want is for the government to answer our questions. It is our right to know what they do with our homes and cities,” says Sukrit. His voice is eventually drowned out by the steamrollers trundling on in the background.