In February 2024, when Congress general secretary Jairam Ramesh told the media that he believed Mamata Banerjee was ‘dil se Congressi’—a Congresswoman by heart—was he trying to appease the West Bengal chief minister or was it indeed his heart speaking?

For, one may ask, can a ‘dil se Congressi’ join hands with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the political arm of the Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which sits on the ideologically opposite end from the Congress? While the nationalism of the Congress united all other identities during India’s struggle for Independence, the Hindu nationalists have pursued exclusionary politics from pre-Independence days.

One of the first decisions Banerjee took after splitting the Congress in Bengal and launching her own Trinamool Congress (TMC) on January 1, 1998, was to make it a part of the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA).

She split the Congress because she believed, and alleged, that the Congress, due to its national political compulsions, was keener on keeping the Left in good humour to prevent the BJP from coming to power at the Centre. This was why the Congress was not going all-out against the CPI (M)-led Left Front government ruling West Bengal since 1977, she alleged.

Preventing the BJP from coming to power at the Centre was not her priority; toppling the Jyoti Basu government in West Bengal was. She eventually helped the BJP come to power at the Centre in 1998 and 1999 and served in the Atal Bihari Vajpayee cabinet.

It was thanks to the alliance with the newborn TMC that the BJP won their first assembly and parliamentary seats in West Bengal—Tapan Sikdar from Dumdum Lok Sabha in 1998 and Badal Bhattacharya from Ashoknagar assembly in 1999.

Can a ‘true Congressi’ ever join hands with the BJP, Bengal Congress heavyweight Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury, the leader of the party in the 17th Lok Sabha and multiple-term state Congress president, has asked several times.

From 1998 to 2006, the TMC contested the 1998 and 1999 Lok Sabha elections as part of the BJP-led NDA, the 2001 assembly election in alliance with the Congress, and again the 2004 Lok Sabha election and the 2006 assembly election as part of the NDA.

Going from one end of the spectrum to the other has been integral to the TMC’s journey. In 2003, Banerjee, famously and controversially, certified the RSS as “true patriots” at an RSS event in New Delhi. She was possibly responding to the adulation BJP Rajya Sabha MP Balbir Punj had just showered on her by calling her ‘Shakshat Maa Durga”, or an embodiment of goddess Durga. She believed the RSS and the BJP could be her only true ally as they would never join hands with the Left.

By 2007, she started saying “All Leftists are not bad,” she respects the “true Leftists”, but the CPI (M) was “a disgrace in the name of Leftists”. By 2014, after Narendra Modi became Prime Minister and the BJP’s vote share in West Bengal recorded a surge, Banerjee courteously met a Left Front delegation and, to their surprise, urged them to save their party from the BJP.

Some changes happened faster—from addressing the organisers of the banned CPI (Maoist) as “brothers” in 2009 to calling them “anti-social” and “criminals” by 2011.

The Turning Point

As the 2004 and the 2006 elections left the TMC’s hopes shattered, the party braved the risk of getting branded as ‘anti-industry’ and went all-out supporting the anti-displacement movements in Singur and Nandigram.

The BJP tried its best to express solidarity with the TMC’s struggle. The TMC had to choose between the BJP and the support of smaller Left parties and rights groups. By then, writer Mahashweta Devi, a known supporter of Naxalite politics and tribal rights movements, and activists like Medha Patkar and Swami Agnivesh, had shared daises with her.

Smaller Left parties like the CPI (ML) (Liberation), Socialist Unity Centre of India (Communist) and CPI (ML) (Provisional Central Committee), several rights-based organisations and prominent intellectuals attended events together with the TMC under the banners of the Singur Krishi Jami Raksha Committee and Nandigram’s Bhumi Uchchhed Pratirodh Committee (BUPC).

In these people and organisations, the TMC found a bigger source of strength than the BJP. All these influences introduced changes in the TMC’s political language. The party borrowed the Left’s old slogans, used old communist protest songs and called for protecting Jal, Jangal, Jameen (water, forests and land) from corporate exploitation, which has essentially been a Leftist demand.

In a decade since its founding, without having any ideological inclination, the TMC had managed to trigger a nationwide ideological debate on the model of development and the role of Leftist parties and organisations in times of the spread of neoliberal development policies.

The party can legitimately claim some credit for the scrapping of the Land Acquisition Act of 1894 and the legislation of the new, more farmer-friendly Land Acquisition Act of 2013, a role more expected from the Left parties than one of the TMC’s background.

Zaad Mahmood, a political scientist at Kolkata’s Presidency University, describes the TMC’s approach as “agenda-based politics.” The description appears quite apt.

The party was launched with the sole agenda of removing the Left Front government. It incorporated some ideological moorings when resisting displacements and criticising the CPI (M)’s development model topped its immediate agenda. It revamped its ideological position when Hindu nationalism threatened the party’s rule. In short, the immediate agenda has shaped the party’s ideology.

In a decade since its founding, without having any ideological inclination, the TMC had managed to trigger a nationwide ideological debate on the model of development and the role of leftist parties.

The ‘All-in-one’ Party

Supporters, critics and independent observers have described the TMC in many ways. The party itself has claimed to be “the real Congress” in Bengal, more Left than the CPI (M) and more authentic Hindu than the BJP, at different times. Lately, they have described themselves as manobik or humane.

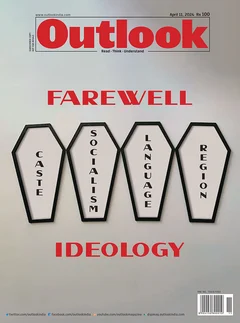

According to political scientist Dwaipayan Bhattacharyya, ideology as a system of thoughts that guided welfarism of the liberal democratic countries and anti-colonial nationalism of the newly independent nation-states changed dramatically following the launch of the neo-liberal political economy and the collapse of the Soviet bloc in the 1990s.

India’s communist parties—which once fought fiercely and split their ranks on ideological grounds—are now driven by a well-meaning yet diffused idea of equality, secularism and socialist democracy without any possible validation of these ideas in sight, he says.

“The TMC had an apparent ideological inclination in its post-2006 rise with the anti-displacement movements, which attracted some Left-leaning intellectuals by its side. However, it has no vision for any long-lasting change. What is an ideology without a vision? All they have is a drive for governmental welfarism,” says Bhattacharyya, a professor of political science at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

He, however, says that in the context of Hindutva ideological dominance in post-2014 India, taking sides itself is an ideological test and that the TMC has taken a clear position by championing inclusive politics against Hindutva’s politics of exclusivity.

“In today’s India, resisting or confronting the Hindutva ideology is an ideological position. Getting a popular mandate against Hindutva ideology is important. When the CPI (M) was in power in Bengal it did not allow Hindutva to get a head start. The TMC also had not shown any rabid anti-minority stance in Bengal even when they were part of the NDA. Now, they are promoting an ideology of inclusiveness,” says Bhattacharyya.

He added that both the CPI (M) and the TMC are trying to create a secular alternative. While the former dissociates from all religions, the TMC offers an inclusive Hindu politics based on Bengali identity, taking elements from both Bengal’s everyday syncretism and the remains of its liberal social reformism.

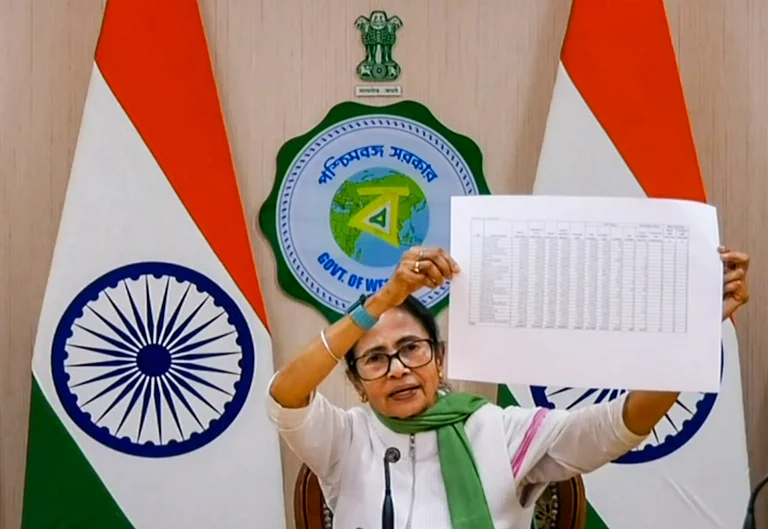

Indeed, that is how Banerjee has been describing her party’s ideology in recent months. “We love everyone,” she says at rally after rally, “Buddhists, Jains, Christians, tribals, Dalits, Muslims, Hindus, Punjabis, Tamils, Odias, Rajbanshis, Gorkhas, Baba Loknath, Ajmer Sharif…” All in one breath.

She says the party’s three slogans—Bande Mataram, Jai Hind and Joy Bangla—reflect its ideology. Of them, the party adopted the last two slogans only in 2019.

The journey has been through a great deal of dilemmas. The TMC toppled the Left Front government in 2011, hijacking old Leftist agendas and slogans. But in its bid to undo the ‘taint’ of having been with the BJP in the past, the party had also taken to overt Muslim appeasement around 2008-09. This, clubbed with the alleged political atrocities on the Left, created the grounds for the BJP to spread after Modi came to power.

Puzzled by the right-wing challenge, the TMC took contradictory moves like trying its hand with Bengali ethnic politics and ‘soft Hindutva.’ From 2022-23, the party explained its ideology more clearly: it comprises three components—unity in diversity, federalism and a humane outlook.

The TMC government celebrates the birth anniversaries of the late Leftist poet Sukanta Bhattacharya and Hindu nationalist icon Syama Prasad Mookerjee. It prides itself on Bengali identity but also opens a Hindi University and declares a three-day holiday on Chhat Puja, a festival of Hindi-speaking Hindus.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

From one perspective, the party is an ideological hotch-potch. But from another, is the TMC in its current shape not a true legacy bearer of the Congress, which has always been a centrist and inclusive platform of varying views and interests rather than a regimented ideological force?

(This appeared in the print as 'Ideological Flip-Flops')