I was about to buy batteries for my recorder for this interview and was avoiding, as usual, a certain unrepentant brand associated with the Bhopal gas tragedy. Sometimes, such independent choices are not even possible in this world which some say is becoming flat. What are your thoughts?

We live in an Age of Spurious Choice. Eveready or Nippo? Coke or Pepsi? Nike or Reebok?—that’s the more superficial, consumer end of the problem. Then we have the spurious choice between the so-called "corrupt" public sector and the "efficient" private sector. The real question is, does democracy offer real choice? Not really, not anymore. In the recent US elections, was the choice between Bush and Kerry a real choice? Was the choice between Blair and his counterpart in the Conservative Party a real choice? For the Indian poor, has the choice between the Congress and the BJP been a real choice? They are all apparent choices accompanied by a kind of noisy theatre which conceals the fact that all these apparently warring parties share an almost complete consensus. They just exchange slogans depending on whether they’re in the opposition or in the government.

So there’s a lack of choice despite political democracy?

The last Lok Sabha election was fundamentally about two issues: the economy and right-wing Hindu nationalism. I would say that in most rural areas, issues of economy were at the forefront of the voter’s mind. During the countdown, the campaign rhetoric of the Congress was about marginalising disinvestment, taking a new look at privatisation, taking a new look at ‘corporate globalisation’? But as soon as it won, even before they took office, senior Congress leaders had begun reassuring the market that it would not make any radical change. Look at what’s happening now. Privatisation and corporatisation are proceeding APACE. Meanwhile, by arbitrarily adjusting the poverty line, by redefining what constitutes poverty, the Planning Commission drastically reduces the official number of poor people to 27 per cent of the population. Half of India’s rural population has a food energy intake below the average of sub-Saharan Africa. Yet one of the first things finance minister P. Chidambaram does is to slash the rural development budget to the lowest it has ever been! The one ray of hope was the Rural Employment Guarantee Act. But I’m not at all sure it will go through. Is it just smoke and mirrors, a game of Good Cop/Bad Cop that trades on the almost saintly status of Sonia Gandhi and the credibility of some extraordinary people in the National Advisory Council in order to garner the Congress some brownie points?

PM Manmohan Singh, who lost a Lok Sabha poll from the posh South Delhi constituency in 1999, is called a decent, incorruptible statesman. Is he able to carry off a neo-liberal agenda because of this non-politician halo?

I don’t know why technocrats like President Kalam and this new breed of bureaucrat/politician seem to have the middle class and the mass media in their thrall. Maybe because they have power without being frayed at the edges by real political engagement. Maybe because they are the architects of the process separating the Economy from Politics—and thereby keeping power where they think it really belongs, with the elite. Manmohan Singh, Montek Singh Ahluwalia and P.Chidambaram have fused into the Holy Trinity of neo-liberalism. Their vision of the New India has been fashioned at the altar of the world’s cathedrals: Oxford, Harvard Business School, the World Bank and the IMF. They are the regional head office of the Washington Consensus. They are part of a powerful network of politicians, bureaucrats, diplomats, consultants, bankers, businessmen and retired judges who trade jobs, contracts, consultancies and vitally—contacts. Right now, for example, there’s a lot in the news about the scandalous Enron contract being "re-negotiated" for the third time—the contract that resulted in MSEB having to pay Enron millions of dollars not to produce electricity. The renegotiation is all very secret (like the initial Enron negotiation). The nodal ministry involved in the re-re-negotiation is the finance ministry headed by P. Chidambaram who, until the day he became finance minister, was Enron’s lawyer. The other members on the committee are Montek Ahluwalia and Sharad Pawar—the two who were instrumental in signing the disastrous contract in the first place. It’s like asking an accused in a criminal case to investigate the crimes he’s been accused of.

Do people in rural India view these technocrats and bureaucrat-politicians differently?

A few years ago (when Manmohan Singh was between jobs), I was in Raipur at a meeting of iron ore workers from the neighbouring districts. I’ll never forget a young Hindi poet who read a poem, called Manmohan Singh kya kar raha hai aaj-kal? (What’s Manmohan Singh doing these days?). The anger in the poem was so acute, so shocking even to me. All the more so because it was aimed at such a gentle, soft-spoken man. The first two lines were: Manmohan Singh kya kar raha hai aaj-kal/Vish kya karta hai khoon mein utarne ke baad. (What does poison do once it has entered the bloodstream?) At the time, I came away disturbed and shaken.... But today? The thing is, rural India is in real distress—and many do link their distress to Manmohan Singh’s reforms when he was finance minister in the early ’90s.

What did you make of the PM’s Oxford address?

Timing is everything, it was an unambiguous political statement. Right now, Western powers and several right-wing academics, like the historian Niall Ferguson, have embarked on a project of valorising Imperialism. This is the argument they use to justify the invasion and occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan and all the ones still to come. At this point in history, for the Indian PM to publicly and officially declare himself an apologist for the British Empire is pretty devastating. After a few cautious caveats in his speech, Manmohan Singh thanked British Imperialism for everything India is today. Ironically, at the top of his list was all the machinery of repression put in place by a colonial regime—the bureaucracy, the judiciary, the police, Rule of Law. He then went on to express gratitude for the gift of the English language—the language that separates India’s elite from its fellow countrymen and binds its imagination to the western world. Macaulay couldn’t have asked for a more dedicated disciple.

The only people who might have a valid reason to view the British Empire with less anger than the rest of us are Dalits. Since to the white man all of us were just natives, Dalits were not especially singled out for the bestial treatment meted out to them by caste Hindus. But somehow, I can’t imagine Manmohan Singh bringing a Dalit perspective to colonialism while receiving an honorary PhD in Oxford.

You once said that on several issues—Babri, N-bombs, big dams, privatisation—the Congress sowed and the BJP swept in to reap a hideous harvest. With the Congress at the helm, what has fundamentally changed?

I’ll be honest. When the BJP lost the elections, in spite of my intellectual analysis of the situation that nothing was going to change economically, I certainly feel less hunted. This is a totally selfish point. I think this incredible communal churning has ceased. The BJP has a far more vicious way of implementing the same policies. I don’t think we can deny that.

What is the future of the BJP?

It’s different in the Centre and the states (like Rajasthan, Gujarat and MP).If you look at the number of seats it won and its voteshare, it does not indicate that it should have fallen apart like it has. It seems to have been held together by the glue of power. And when that went, it fell apart. I am not mourning this. They seem to have exhausted this Ramjanmabhoomi agenda totally. But we also need to have a strong Opposition in this country....

The BJP doesn’t seem to have the time for that. But the Left thinks it is playing opposition.

I think the Communist parties run the risk of making themselves ridiculous by contesting everything initially and then caving in eventually. They are playing the role of a ‘virtual opposition’. This Left-Congress combine could well become the secular version of the parivar. All the arguments are reduced to being family squabbles.

What does it mean to be independent today? Has Independence Day become a mere annual ritual?

As corporatisation and privatisation proceed APACE and more and more people are rendered jobless, homeless, and have no access to natural resources, anger and unrest will build. The central function of the State will increasingly be to oversee the repression of an unemployed, dispossessed population on behalf of the corporates. The State will have to evolve into an elaborate tyranny which retains all the rhetoric of democracy. Look at what’s happening in Orissa—the new crucible of corporate globalisation. Multinational mining companies—Sterlite, Vedanta, Alcan—are devastating Orissa’s hills and forests for bauxite. They say Kashmir is like Palestine. True. But Orissa is getting there too. Orissa is a police state now. For some years now, there has been a resilient, feisty, anti-mining movement in Kashipur. You ask what independence means to most Indians—visit Kuchaipadar, the extraordinary little Adivasi village at the heart of the Kashipur struggle, and you will have your answer. Kuchaipadar is surrounded by police. People cannot move from one village to the next. Cannot hold meetings, rallies or protests. Over the last two years, they have been shot, beaten, lathicharged, jailed and several have been killed. Last year, on Independence Day, Kuchaipadar’s villagers hoisted a black flag. That’s what independence means to them. Oh, and who’s on the board of directors of Vedanta, one of the biggest mining companies prospecting in Orissa? P. Chidambaram, who resigned on the day he was appointed FM; David Gore-Booth, former UK high commissioner in India; Naresh Chandra, former cabinet secretary and ex-Indian ambassador to the US, and former chairman of the Foreign Investment Promotion Bureau. It’s a bedroom farce with blood on the tracks.

There’s been an outsourcing boom. The Indian IT and IT-enabled services industry business touched $17.2 billion in 2004-05. Fifty per cent of Fortune 500 companies are clients of Indian IT firms. Surely, some people are benefiting?

Of course, some people benefit. Otherwise there wouldn’t be the kind of vocal support that it does have among sections of the people and the national media. The outsourcing industry has created thousands of jobs, mostly in urban areas, and in India that small percentage amounts to a huge number of people. But in return, there is a larger section that gets disempowered, dispossessed. The point, as always, is: who pays, who profits? This section that benefits is full of the joy of having cars, mobile phones, lifestyles that they could not even have dreamt of a few years ago. They control the media, television, they make the movies, they fund them, act in them, distribute them. They form a little universe of their own, sending each other signals of light. For the rest, the darkness deepens. However, be assured: if at any point outsourcing begins to cost America, if it begins to affect their population seriously, outsourcing operations will be shut down in a flash. We live on sufferance. And that’s not a safe place to build a home.

While the UPA government initially promised to ensure some kind of affirmative action in the private sector, 21 leading industrialists led by Ratan Tata have pronounced the entire generation of Dalit/ tribal people with degrees from Indian institutions "unemployable". They have decided to create a new generation of Dalits/Adivasis through "skill upgradation".

When it appears that Dalits and other backward classes are getting represented suddenly in our democracy, people in power will find ways of undermining this process. That’s what privatisation and corporatisation is about. Dalits, Adivasis and other dispossessed people should realise that they can’t bank on the politics of compassion. Because there is none left, and they have no leverage on Ratan Tata.

Dalit spokespersons such as Chandrabhan Prasad have been arguing that if US corporates can employ blacks under the policy of diversity, can’t Ford and GE do similar social engineering here?

It was not an act of compassion on the part of Ford and GE. At the time in the US, the black civil rights movement was an international force to be reckoned with. So some negotiation had to happen. Power concedes nothing unless it is forced to. No one knew that better than Ambedkar. It was at the centre of his brilliant demolition of Gandhi’s argument in ‘Annihilation of Caste’. Right now, the Dalits have no leverage. Today, the Dalit movement is fractured and scattered. We need a strong Dalit movement. Unfortunately, it is not a movement that anyone has to negotiate with, least of all India Inc.

The UN this April appointed two special rapporteurs to investigate and find solutions for caste-based discrimination in India. Can something come out of this internationalisation of the Dalit issue?

The UN is such a shaky organisation. It has not been able to bring any kind of authority to international issues of late, as we have seen from what happened in Iraq. The UN was used to disarm Iraq before the attack, and then was just kicked aside. Maybe their (the UN rapporteurs’) coming is a good thing. But I’ll believe it when I see something really happening. Because today India is a market. All the major corporations are looking at India with greedy, greedy little eyes. Whether it is the genocide that took place in Gujarat, or whether it is everyday discrimination against Dalits, I don’t see any of this being allowed to come in the way of Thomas Friedman’s dreamland project. The treatment of Dalits in India is by no means any less grotesque than the treatment of women by the Taliban. But is any of the violence against Dalits in the Indian or international mainstream press? But if you are a willing and open market, will they bomb the caste system out of India, like they wanted to bomb feminism into Afghanistan? I am not a believer in these UN-driven institutional therapies. You have to wage your struggles, you have to put your foot in the door.

That brings us to Friedman’s dreamland, New Gurgaon, an outsourcing hub.The Congress harped on the ‘aam aadmi’ before the election.But the aam aadmi got pulped in Gurgaon.What lessons do we learn?

Unfortunately, underpaid as they are, and humiliated as they have been, the Honda workers are not aam aadmi. They’re supposed to be the real beneficiaries of globalisation.At least they have work. Far from the glare of TV cameras, the aam aadmi has been facing not just the lathi, but also goli—in Orissa, Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Kerala.The atrocity on the Honda workers happened at the heart of corporate paradise. In Thomas Friedman land. Trouble broke out in the bubble.Gurgaon is one of three New Economic Zones where existing labour laws have never really applied.In the race to the bottom—cheaper labour, longer hours, more ‘efficiency’—the company’s labour contractors, like all labour contractors, hired ‘trainees’ and paid them stipends, not salaries. When their ‘training’ was through, they fired them in order to hire more ‘trainees’.

The TV coverage cuts both ways—it can either frighten people or enrage them. I think the police was given instructions to be so brutal and repressive in order to make an example of workers so that others would not dare to do this again anywhere. But the uproar that has ensued and the fact that Honda has been forced to reinstate those who it sacked could mean that workers realise that when they act together they do become a force to reckon with.

Doesn’t the Indian elite and the middle class conveniently vent its anger on the political class and yet align with the state on most issues?

This is again about the hollowing out of democracy. Even as we sell our credentials on the international stage as a democracy, even if there’s democracy at the level of panchayati raj or Laloo and Mayawati, there’s a certain amount of fear in the Indian elite that the underclasses are being elected. How do you undermine that? You undermine it by corporatisation, by creating a situation in which the politicians may hold the theatre and the audience, but the real economic power has shifted from their hands. The elite in Pakistan has seen so little democracy. So, strangely enough, they know the difference between themselves and the state. Najam Sethi can be rounded up, beaten up and put in jail. People tell me: if you had been in Pakistan, you would have been shot by now. But whoever comes to power (in India), the chances of that happening to N. Ram or Vinod Mehta are still quite remote. The Indian elite is fused with the state in many ways. We think like the state. We’re all wannabe policymakers. No one’s just a citizen.

What do you think of India’s new role as a US ally?

The Indian government should seriously study the history and fate of former and present US allies—the world is littered with the carcasses of their people. Only a few years ago, they were shaking hands with Saddam Hussein, and a little before that they were doing it with the mujahideen. Pakistan, Iran, Indonesia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Chile, other countries in Latin America and Africa. Look what happened to Argentina. And the former USSR. We are tying ourselves into an intricate economic and strategic web. Once we’re in, there’s no out. We’re in the belly of the beast. Once you’re there, you eat predigested pap. You behave. You do what you’re told, buy what you’re sold. If you disobey, you’re in trouble. Already, you can see the signs. Condoleezza Rice says the oil pipeline deal with Iran will be a bad idea.

Manmohan, on cue, promptly declares to the Washington Post that he thinks it will be very hard to raise money for the project. What’s that supposed to mean?

But experts say the nuclear deal with the US puts India in a ‘win-win’ situation.

If a swordfish signs a deal with a crocodile, can it be a win-win deal? Right now, it’s strategically important for the US to allow us to believe our own publicity about being a superpower. India is not a superpower. It’s just super-poor. It’s not enough to discuss the nuclear ‘deal’ as an issue about nuclear energy and nuclear bombs—though that’s important too. Where are the studies that show that the right kind of energy for India is nuclear energy? Have we seriously explored alternative forms of energy? Why has the debate been posited as one solely between nuclear energy and fossil fuels? What are the pros and cons of nuclear energy versus energy from fossil fuels? Why has there been no public debate about these things? But the real issue is not about whether India has escaped nuclear isolation. It’s not about whether the government has capped its nuclear programme. It’s about whether it has capped its imagination. It’s about whether it has restricted its room to manoeuvre politically, economically and morally. Has it imbricated itself intimately into an embrace it can never escape?

But both Gen Musharraf and Manmohan Singh want to be Bushies.

We have two begums competing for the attention of Sheikh Bush. Both of them are fighting for attention and are jealous of each other.

Edward Said would have perhaps approved of this interesting Orientalist metaphor. But seriously, what should be the terms of the nuclear debate?

Actually, it is Orientalist and sexist. I shouldn’t have said it...anyway. For all these experts appearing to debate and disagree on the nuclear issue, these are matters of state and foreign policy which are not to be debated in terms of morality and principles, because that’s not how foreign policy works. It’s about ‘strategy’. I know that. But I don’t want to think like the state. As a human being, I ask: is it alright for our prime minister, on behalf of all of us, to dine at the high table and wave from the balcony arm-in-arm with a liar and a butcher called President George Bush? A man who has lied about WMDs in Iraq, whose lies have been exposed, whose military cowardly killed 1,00,000 Iraqis after getting the UN to disarm Iraq, and killed 25,000 more subsequently? It’s worth keeping in mind that collaboration in wars against sovereign nations is a war crime. And also, if Bush is so acceptable to them (the Congress), why lose sleep over Modi, our own overseer of mass murder? We are told it’s a strategic alliance with the US, and morality doesn’t apply. But why is it that every time a government goes to war, the only reasons offered are moral reasons? "To spread democracy, freedom, feminism, to rid the world of evil-doers?" Why is it that states expect morality of us, but we as individuals can’t debate an issue in moral terms? I don’t understand.

You’ve travelled in Kashmir...

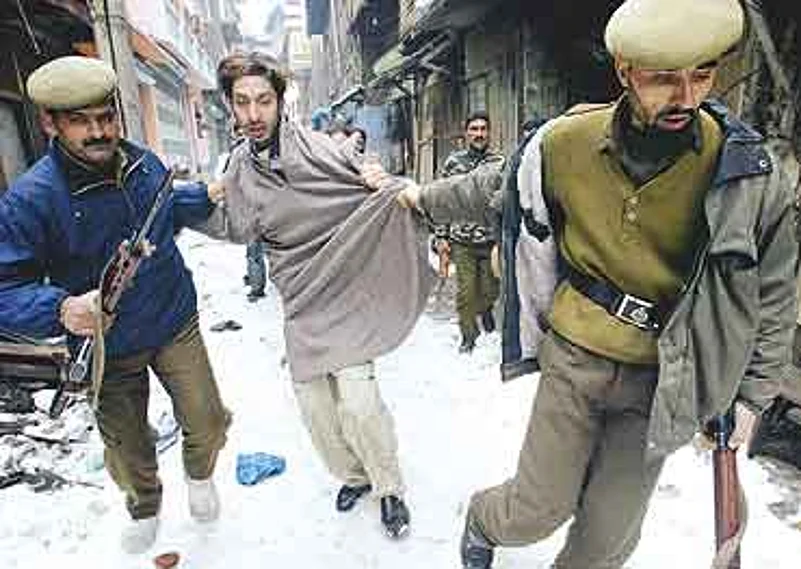

It’s impossible to pronounce knowledgeably on Kashmir after just a few short trips. But some things are not a mystery. Hundreds of thousands have lost their lives in this conflict. Both Pakistan and India have played a horrible, venal role in Kashmir. But among ordinary Kashmiri people, Pakistan still remains an unknown entity—and for that reason it’s become an attractive idea, an ideal even, conflated by many with the yearning for ‘azaadi’. It’s ironic that a country that is a military dictatorship should be associated with the notion of liberation. The ugly reality of Pakistan is not something that most Kashmiris have experienced.The reality of India, however, to every ordinary Kashmiri, is an ugly, vicious reality they encounter every day, every ten steps at every checkpost, during every humiliating search.And so India stands morally isolated—it has completely lost the confidence of ordinary people.According to the Indian army, there are never at any time more than 3,000-4,000 militants operating in the Valley. But there are between 5,00,000-8,00,000 Indian soldiers there.An armed soldier for every 10-15 people. By way of comparison, there are 1,60,000 US soldiers in Iraq.Clearly, the Indian army is not in Kashmir to control militants, it is there only to control the Kashmiri people. It is an army of occupation the Indian media—and here I include the film industry—has played a pretty unforgivable part in. In totally misrepresenting the truth of what’s really going on. How can we even talk of ‘solutions’ when we simply deny the reality?

State repression, religious fundamentalism and corporate globalisation seem interconnected. But hasn’t resistance to this nexus become symbolic, tokenist, NGO-ised and even a career for some professionals, including some would say for you?

It’s true. Sometimes NGOs wreck real political resistance more effectively than outright repression does. And yes, it could be argued that I’m yet another commodity on the shelves of the Empire’s supermarket, along with Chinese cabbages and freeze-dried prawns. Buy Roy, get two human rights free! But between the NGOs and Al Qaeda—frankly, I’m with the many millions who are looking for the Third Way.

And the prognosis for the War on Terror?

Clearly, it’s spreading. Empire is overstretched. The Iraqis have actually managed to mire the US army in what looks like endless, bloody combat. More and more US soldiers are refusing to fight. More and more young people are refusing to join the army. Manpower in the armed forces is becoming a real problem. In a recent article, the remarkable un-embedded journalist Dahr Jamail interviews several American marines who served in Iraq. Asked what he would do if he met Bush, one of them says: "It would be two hits—me hitting him and him hitting the floor." It’s for this reason that the US is looking for allies—preferably low-cost allies with low-cost lives. Because the media is completely controlled, no real news makes it out of Iraq. But last month, I was on the jury of the World Tribunal on Iraq in Istanbul. We heard 54 horrifying testimonies about what is going on there, including from Iraqis who had risked their lives to make it to the tribunal. The world knows only a fraction of what’s going on. The anger emanating out of Iraq and Afghanistan is spreading wider and wider.... It’s a deep, uncontrollable rage that you cannot put a PR spin on. America isn’t going to win this war.

It has been eight years since ‘The God of Small Things’. Is there a second novel in you or has too much politics meant the end of Arundhati Roy’s imagination? You have also been talking of disengaging from political writing?

All writing is political. Fiction is especially subversive. But it’s time for me to change gear. I am sort of up for anything right now, which is exciting. Let’s see what happens.

Any positive thoughts to end this dark conversation?

Let me share a sweet little thing. I saw a news report about two Adivasi girls getting married to each other. And the whole village was saying: if that’s what they want, it’s fine. They had this ceremony, with all the rituals and customs, and they let them get married. That’s a moment of magic. It reveals their level of modernity, of their sophistication. Of their beauty.