What is the colour of Mumbai? Blue for the sea and the skies above it? But the sea has long ceased to be blue. It’s more of a grey-green now and the sky is too far away for the city to lay claim to it. With its mills gone, Mumbai is no longer a blue-collared city anymore. Does the city reflect a shade of the Dalit blue then? Red? But the Communists have come and gone. Red has had its moment in Mumbai’s working-class history. The city has also had its tryst with blood red, with its riots, gang wars and encounter killings. But things have been quiet for a while. Green? Trees no longer are a source of shade in Mumbai. Concrete towers are. But green, one could argue, is still the colour of the ‘other’ in the city cohabiting with saffron.

White? You’ve got to be really lucky to pull off white in Mumbai. You would need to hop in and out of air-conditioned cars, into cool lounges, clubs, bars or restaurants. White is terrible if you expose your collar or sleeves to the grimy elements. With just less than half the population housed in slums, white is not the predominant stroke one could paint the city with. Saffron then? Close, but which shade? Bal Thackeray brought it into vogue in Mumbai. But now Devendra Fadnavis and the BJP have a patent on the primary shade, Shiv Sena’s saffron seems to have faded and Eknath Shinde now represents its third shade. It is a coincidence that green, white and saffron are the defining shades of the Indian Tricolour.

ALSO READ: Mumbai: The City That Resurrects Itself

But it is no coincidence that the colour of Mumbai, the financial capital of the country, is the colour of money: Black. It is a colour which subsumes every other colour within, including the currently warring shades of Hindutva, which have installed and deposed a few governments in the state capital.

While the two factions—with the BJP aiding one—fight ostensibly over the quality of the Hindutva distillate brewed in either camp, the real battle behind the obvious political bickering is invariably money. In this case, specifically over Mumbai’s purse strings. The one who holds the key to this economic behemoth of a city, controls the country’s financial axis.

Mumbai’s 22 million-plus population is home to double the number of billionaires compared to Delhi. In its 2021-22 budget, the richest civic body in the country, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation presented a budget of Rs 39,038 crore, bigger than the size of the budget presented by each of the seven Northeast states (barring Assam) and Goa. The BMC’s budget for 2022-23 is a staggering Rs 45,949 crore.

Eknath Shinde’s revolt against Uddhav Thackeray comes ahead of the crucial BMC polls—due this year—for 236 seats. Since 1971, the Sena has installed 21 city mayors. The saffron party has been in control of the civic body since 1996 without a pause, drawing strength mainly from its anti-migrant campaign, at times even violent.

The first migrants from the Konkan and Marathwada regions were drawn by the new, cash-rich textile industry in the 19th century. Subsequent waves of migration from other parts of the mainland lent the city its cosmopolitan appearance. The revenues generated from the textile industry gave the city its first banks, a modernised port, and the stock market. Its increasing population gave rise to railway, tram networks, hospitals and a civic authority to deal with urbanisation challenges.

Not much changed after Independence, as the city’s wheels of commerce kept churning out wealth. Hordes continued to migrate to Bombay from across India, hoping to make it big or just to eke out a steady living. Many made do, some succeeded, while the unsung thousands were ground and cast aside into the city’s margins as Bombay grew exponentially.

The late 1950s threw up a new challenge to the city’s claim of being a cosmopolitan hub. In 1956, the States’ Reorganisation Act proposed that Bombay should be the capital of a bilingual state comprising Gujarat and Maharashtra. Keshav Prabodhankar Thackeray, a social reformer, was one of the key leaders of the Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti which demanded a separate state of Maharashtra on linguistic lines with Bombay as its capital. Its campaign drew in a cross-section of Marathi intelligentsia. Thackeray’s son, an aspiring cartoonist named Bal, was deeply influenced by the campaign that led to the creation of Maharashtra, with Bombay as its capital in 1960.

In the same year, Thackeray, who started his professional career as a cartoonist at the Free Press Journal, launched his own magazine, Marmik, which was critical of the Congress. After massaging the Marathi heart for a few years with Marmik, the Shiv Sena was born in 1966. Its election symbol, bow and arrow, would later pierce the soul of the Marathi manoos.

Thackeray toured the city and his speeches inspired thousands of Maratha youth to join forces with him as Sena’s maules (as Shivaji’s band of followers were referred to). Right from the outset, the Sena was associated as a movement for Maharashtra’s native sons. Former deputy chief minister Chhagan Bhujbal, now an NCP leader, was swayed by Thackeray’s oratory. “Balasaheb Thackeray came forward for the jobs of Marathi people. In the very first speech (at) Shivaji Park, I became a Shiv Sainik…I don’t have parents. I used to consider Balasaheb and Maa saheb (Meenatai, Thackeray’s wife) as my parents,” Bhujbal said in a 2021 interview. Bhujbal, incidentally, was one of Thackeray’s first lieutenants to ‘betray’ the Sena when he joined the Congress at Sharad Pawar’s goading in 1991, around three decades before Eknath Shinde.

Thackeray’s personality cult had also spilled over in the adjoining Thane, where Anand Dighe replicated the Sena’s Bombay success. Dighe had modelled himself after Thackeray, ruling Thane just as Thackeray bossed Bombay. The rich and the powerful in Thane, and the common folk like vada pav sellers, vegetable vendors etc., queued outside Dighe’s residence. Dighe’s rising popularity among Sainiks in Thane had made the Sena founder uncomfortable over time, much before Eknath Shinde—who was mentored by Dighe himself—eventually toppled Uddhav.

Over time, Thackeray controlled the affairs of Mumbai from this throne at his Bandra home ‘Matoshree’, as he stroked the silvery manes of sculpted lions, which served as hand rests. Above the seat at the apex of the backrest was an image of a tiger baring its fangs. Sena leaders claim that after Thackeray’s death in 2012, no one dared sit on the throne. Uddhav Thackeray certainly did not in public. Even after he took over the reins of the party founded by his father and was sworn in as chief minister in 2019.

Thackeray Senior found a place in the hearts of Mumbaikars, the ones who loved to see him have a go, gesticulating wildly with one hand at the ills of Mumbai and Maharashtra—with the other hand on his hip—during the annual Dussehra speech at Dadar’s Shivaji Park. Faced with thousands of Sainiks—eager to hear his speech littered with Maratha pride, smart turn of words, witty phrases, abuse, slander and the nectar of Hindu resurgence—Thackeray came into his own.

On several occasions, he openly admitted to his fascination with another robust orator, Hitler. The praise for the German dictator came with a rider though. “I am a great admirer of Hitler, and I am not ashamed to say so! I do not say that I agree with all the methods he employed, but he was a wonderful organiser and orator, and I feel that he and I have several things in common. Look at the amount of good we have done in just six months in Maharashtra. Actually, we have too much sham-democracy in this country. What India really needs is a dictator who will rule benevolently, but with an iron hand,” he had said in the 1990s.

Thackeray’s infamous and oft-repeated ire against Muslims wasn’t the first instance when he had targeted a specific community. Soon after the Sena’s birth on June 19, 1966, Bombay’s South Indian community was on Thackeray’s radar. That campaign was marked by violence and vitriol. Rolled into the hate campaign against South Indians was the specific and violent targeting of Communist party cadres who led labour unions.

The Sena strapped itself into Hindutva mode in 1984, with his speech at a huge rally in Shivaji Park on January 22. It was at this rally, party insiders say, that he first proposed the idea of the confederation of Hindu organisations. In the process, he also earned the prefix ‘Hindu Hriday Samrat’ (Emperor of the Hindu Heart). “He had a three-point programme of this Hindutva plan he had talked,” says a former Shiv Sena leader who had worked closely with Balasaheb. “He wanted Muslims to be like Hindus; marry only one woman and adopt family planning to have smaller families. He wanted Muslims to support the ban on cow slaughter. Balasaheb wanted Muslims to accept this as a Hindu Rashtra.”

Sometime later, aided by manoeuvres by BJP leader, the late Pramod Mahajan, the Sena and the BJP entered into an alliance. “It is Balasaheb who first said that he will make Hindus vote as Hindus. Not as Dalits, Marwaris, Brahmins or others. Hindutva was Balasaheb’s brainchild, which the BJP has adopted as their own,” the leader adds. Over the years the party’s Hindutva agenda took the Shiv Sena out of Mumbai and into its suburbs. It also helped the party spread its wings to other parts of the country, though it is strongest in Maharashtra. This aggressive rollout of the saffron agenda also pulled youngsters towards the party. “I was attracted to the party by the saffron flag. Balasaheb had also told us garv se kaho hum Hindu hai (say with pride that you are a Hindu). This is why I joined the Shiv Sena,” Ganesh Phadke, a shakha pramukh, tells Outlook. The Sainiks adopted their chief’s dressing style too.

While it was Hindutva which helped the party get a foothold in other parts of Maharashtra, it was the Marathi manoos agenda which helped them create a strong foundation in Bombay. It could not have been any other way in the city, where the Sena claimed the Marathi manoos were being swamped out of contention by migrants. “The sons of the soil was a subject which was very close to Balasaheb’s heart,” says Arvind Sawant, the party’s south Mumbai MP. “He would tell us that if we did not look after them no one would.”

In the later years after the party installed its first chief minister in Maharashtra, the Shiv Sena started a slow march away from the Hindutva plank as it tried to broaden its base. The core reason behind this shift, according to those in the know, was foreign investment; in other words, money. “The party was concentrated in Mumbai and realised that foreign investments would not come into the state if there was political negativity and sectarian violence,” says a businessman, who had been heckled by the Shiv Sena Kamgar Union for employing north Indian labourers.

After Uddhav took over the reins of the party, the Shiv Sena was slowly converted into a brand with a modern and inclusive narrative. The watering down of the party’s traditional hardline stance by the Thackeray dynasts suggested a more mellowed core. But party officials claim off-the-record that the change in the party position on some core issues could also be construed as a sign that the party is in the process of evolving with time. Uddhav’s idea of building an inclusive Shiv Sena brand clashes ideologically with the brand Shiv Sena that Balasaheb had built. The recent Shinde rebellion could well be a result of the new brand positioning that Uddhav had carved out for the Sena.

The Sena is also confronted by a bigger player in town, the BJP, whose Hindutva appeal is broader, more organised, better articulated, well-funded and not parochial, limited to a state of a region. Even when he was alive, Thackeray was uneasy about sharing space with the BJP, then an ally. An undated video grab of Balasaheb Thackeray delivering a speech, tweeted recently by the Sena’s youth wing, has the leader saying: “We have tolerated you (the BJP) because of Hindutva, but we will not tolerate it every time”.

Whether Eknath Shinde’s political histrionics pay off in the long run or not, the Shiv Sena needs the Thackerays as much as the Thackeray dynasts need the Sena. It is a matter of mutual survival. The Sena’s power lies in the surname of their founder. Without the Thackeray surname, the Shiv Sena has no identity. It is just another political party peddling a saffron sun. Something the BJP is way better at.

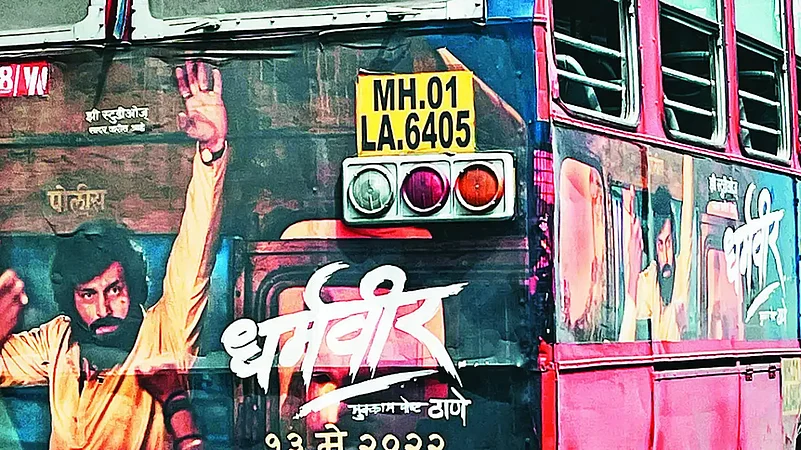

More often than not, Mumbai’s street posters convey the city’s biggest stories before the media does, if one can read through them. Uddhav Thackeray’s time was up. His posters are off. But recently, stark black and white posters flooded Mumbai’s streets featuring a smiling Devendra Fadnavis. The posters referred to him as Devmanus (person with god-like virtue). The posters hint at his ‘sacrifice’ of the chief minister’s post in favour of Eknath Shinde. Shinde too is named after a saint, Sant Eknath. But he isn’t Mumbai’s god yet.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Eye of the TIGER")