Tractor-trolleys laden with sacks of mostly soybean form a serpentine queue outside the foodgrain mandi in Mandsaur. Farmers make their way inside in ones and twos, unpack the bags and unload their produce among growing mounds of soybean in the wide mandi yard. A reasonably good monsoon has ensured a bountiful harvest for farmers in the Malwa region and the windfall is visible at the Mandsaur mandi. As far as the eye can see, it’s just mounds of soybean—in the open and under tin-roof platforms. There are other crops too, mostly pulses like urad and black bean, black channa, and spices such as fenugreek or garlic. On another day, in another time, auction day would have meant happy tiding for the peasants, the day of encashing months of hard work. But not today. Farmer after farmer share woes about falling prices and rising inputs. But mostly about insensitive governments, either in Delhi or Bhopal.

Mandsaur may not be a microcosm of Madhya Pradesh. But this place in the state’s Malwa region presents a pretty good picture of the growing farm unrest that appears to be brewing in other parts as well. For a state going to the polls this month—November 28—this is not good news for the ruling BJP, aiming to capture power for the fourth straight time. And it was in Mandsaur that five farmers were killed in June last year in police firing during protests against the government’s policies. Many allege the crackdown was a manifestation of the government’s “anti-farmer” policies.

“In the past four years, the central government has sacrificed farmers’ interest to control prices of food products. It is ironic, considering that prices of fertilisers have been raised and the quantity in each bag reduced, power and diesel prices have risen, as has labour cost. But farmers’ income has not risen,” Gunvanth Patidar, vice-president of Mandsaur zila parishad, says. He says that five-six years ago, soybean fetched farmers over Rs 5,000 per quintal but market rates are currently below even the minimum support price (MSP) fixed by the government.

On days, desperate farmers have been forced to sell their produce for as low as Rs 2,500 per quintal, just to ensure they have cash to sow the next crop. Patidar resigned from the BJP in October to take up the farmers’ cause.

Despite chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan’s frequent claims of farm sector success, official data reveals the growing crisis in stark numbers. Between February 2016 and mid-February last year, 1,982 farmers and farm labourers committed suicide in Madhya Pradesh which is one-tenth of the 21,000 farmers who have taken their lives in the state in the past 16 years. The National Crime Records Bureau, which collates the data, attributes crop loss, failure to sell produce, inability to repay loans among the reasons for the suicides.

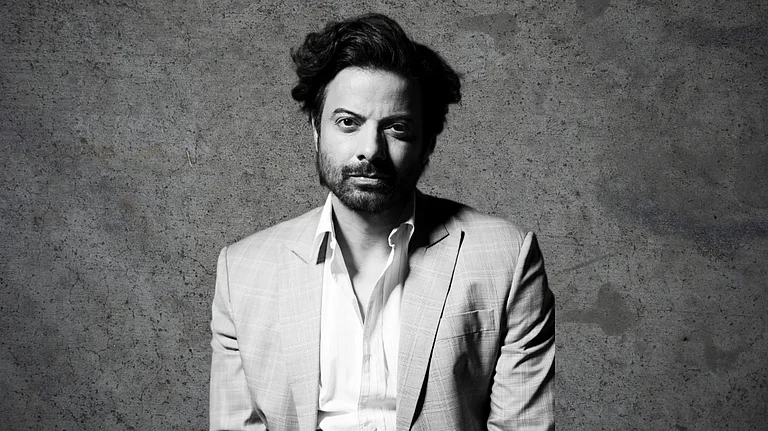

Surendra Singh Songara shows the bullet wound from last year’s police firing in Mandsaur

At the Mandsaur mandi, these very reasons form the basis of the farmers’ discontent. “What we are getting is less than what we used to get five years back when the Congress was in power at the Centre,” says Maango Singh of Pipal Khunta village. “Today, we are not even able to recover our cost of cultivation. More than half of what we get for our produce goes to clear our dues,” adds Singh, who has brought 40 bags of soybean to sell. Singh says he backed the BJP in the previous polls, but has made up his mind to “vote for a change” this time.

A majority of the farmers Outlook spoke to in villages around the Mandsaur and Pipaliya mandis blame government policies, particularly the much-touted Mukhyamantri Bhavantar Bhugtan Yojana, a direct benefit transfer scheme under which farmers are paid the difference between the average market price for a particular commodity and the MSP. This October, Bhavantar has been replaced by a central scheme, the Price Deficiency Payment Scheme (PDPS) for soybean, the major cash crop of MP, but most of the farmers appear to have no idea about the change.

“The Bhavantar scheme is providing no benefit to farmers except in the case of onion and garlic. This year, onion growers too will fail to get good prices owing to the government’s decision to import onion to check domestic prices,” says Mahendra Patidar, president of the Kisan Kranti Sena, a group affiliated to Hardik Patel, a Patidar leader known for his strong anti-BJP stand. Till early October, onion was selling for Rs 10-Rs 12 a kg in the mandi but now prices hover between Rs 10 and Rs 2 following the push for imports. Mahendra is sure the BJP will not get a fourth consecutive mandate. “It is not as if the Congress is winning. The change will happen as the BJP is slipping in popularity due to their policies,” adds Mahendra, who is banking on the Patidar community’s influence in 60 of the state’s 230 assembly seats to beat the BJP.

Prem Chand Meena, commissioner of agriculture produce, says under the PDPS farmers can get up a compensation of Rs 500 per quintal if the market price of their produce falls below the MSP. Under PDPS, the Centre ensures remunerative price to farmers without physical procurement. The difference between the MSP and market price is paid directly into the farmers’ bank accounts. The compensation will be given after studying the average market prices in MP, Maharashtra and Rajasthan, the three major soybean-producing states. However, there is a catch. Only those produce that meets the quality standards set by the government will qualify for PDPS benefit, says Meena.

Faiz Ahmed Kidwai, managing director of the Madhya Pradesh Rajya Krishi Vipanan Board, blames market forces for the dip in prices. “Since the past two-and-half-years we have seen a dip in prices of most agriculture commodities and these are due to market-related factors. For example, in the case of soybean, the prices are akin to those in Chicago. Similarly, the prices of most produce are determined by market forces.” But he adds that under the PDPS, farmers will get fair compensation if the prices fall. He agrees that soybean prices have dipped post-October 20 but says it’s only by Rs 50 to Rs 100 for each quintal.

Farmers blame the new scheme for the sudden dip in market prices. They say the compensation benefits traders and the government as the market price of soybean prior to the launch of the scheme on October 20 was higher at Rs 3,500 to Rs 3,600 per quintal. While the compensation could help to bridge the gap between MSP of Rs 3,399 a quintal and the market prices, the farmers find the wait for compensation too long and uncertain.

Garlic growers look at a BJP poll slogan near the Pipaliya mandi

Most farmers claim that the past four years have been particularly bad as implementation of numerous farmer welfare schemes remaINS poor. Kedar Sirohi, an agriculture management graduate and activist, says the state government’s policies are based on incorrect data and hence fail to deliver. He cites the case of forced selling of soybean at as low as Rs 900 per quintal last year when global prices were firm. “As the government policies are based on wrong data, the impact on the ground is way off the mark whether on agriculture produce, seed and fertiliser requirement or the import/export policy. We need to gather proper data to resolve half of the problems,” says Sirohi, who last month joined the Kisan Congress Union, as he felt the need for a political platform to raise the farmers’ cause.

For many others, the wounds and pain of last year’s police firing—which also injured six others—are still raw. After all, a life can’t be compensated by Rs 1 crore, given to each deceased’s family. The wounded got Rs 5,000 and free medical treatment. Narayan Singh, a postgraduate in law, who farms while also helps victims get compensation, says the government seems to have no clue how to address farmers’ issues, particularly falling incomes and rising costs. “The governments, both in the state and at the Centre, seem to be working for the traders and industrialists and not farmers. All of us voted for BJP… in the hope that the government will help to improve our incomes. But the way things are going, farmers will soon be left with begging bowls,” says Narayan, pointing to Surendra Singh Songara, one of the injured in the police firing. He survived a bullet that passed through his chest but it left him incapable of working for too long.

In Richa and Chilodh Pipaliya villages, where families of some of the victims live, there is lingering anger. Jadgish Patidar laments that his sister-in-law is still to recover from the trauma of her husband, Kanhaiyya Lal Patidar’s death in the police firing. Though the compensation of Rs 1 crore has ensured financial protection for the two school-going children, there is anguish in the family and among villagers who daily gather near Kanhaiyya’s statue to discuss the problems of farmers. Praful Patidar, coordinator of Naujawan Kisan Sabha, is sure the farmers will retaliate against the government which is yet to file an FIR or take any action against those “guilty” of firing on the farmers.

Umra Singh of Ujjain points to the problems faced by licensed opium growers in Mandsaur who have last year’s stock in hand and have no way to dispose it legally (the government agencies having failed to acquire it) before they can harvest the new crop. The fear of police harassment looms large if anyone sells the produce in the market on the sly. The market price is anywhere over Rs 1 lakh a kg but the penalty if caught is several-fold more. The result is, farmers like Yashwant Singh of Richa village have to guard their opium crop so that it is not stolen. With over 40,000 licensed growers, Mandsaur is the largest opium-growing district in the state.

While the BJP government is facing growing anger, the opposition Congress also draws ridicule from many. Umra Singh, for one, mocks some Congress leaders, including a former prime minister who advised farmers to grow red chilli instead of green chilli as the former fetch better price in the market. “How does it help whether it is the BJP or Congress, as both don’t understand agriculture and farmers’ needs,” he says. Some among the young farmers speak of taking the ‘NOTA’ option as neither the Congress nor BJP have succeeded in earning their trust. The BJP can also take heart from others like Mahinder Gwala, who says he knows whom to back in a two-party state. “We have problems but all 90 members of my family will vote for the BJP as always,” he says.

In the fertile farmlands of Mandsaur, political allegiance still grows tall. As does farmers’ discontent and anger.

***

- Mandsaur presents a good picture of the growing farm unrest that appears to be brewing in other parts of MP.

- Till early October, onion was selling for Rs 10-Rs 12 a kg in the mandi but prices have now slumped to as low as Rs 2.

- Farmers say the past four years have been particularly bad as implementation of the welfare schemes remains poor.

By Lola Nayar in Mandsaur, MP