Twenty-four-year-old J’s* (name withheld) mother was pregnant with him in June, 1997, when the Paite-Kuki conflict broke out in the tribal-populated hills of Manipur. The Kuki family had lived in H Khopibung village of Saikul at the time. His mother recalls how they had to run away from their homes in the middle of the night in a bid to escape the ethnic violence that had unfolded in the region following the massacre of at least 10 Paite men in one night by armed militants belonging to the Kuki National Front (KNF). J’s parents fled the village and lived for days in relief camps before finally settling down in New Lambulane, a neighbourhood in the East Imphal region. Over the years, the family rebuilt their life. J was born and his sister followed soon. Almost 25 years later, J and his family were displaced once again in May 2024 due to ethnic clashes, this time between the Kukis and valley-dwelling Meiteis. “All the memories and trauma of those years came flooding back,” J’s mother recalls inside a rented house in Kangpokpi district of Manipur. This time, however, was even worse. J’s sister was allegedly gang-raped by armed Meitei militia. The family has lodged an FIR in the case, but remains shaken; investigations have been slow. J is jobless as he lost all documents in the violence, his father is too ill to work, his mother makes ends meet by selling vegetables on a cart, while the sister recuperates from her mental and physical wounds.

A year since the violence, the precarious lives that the survivors of the ethnic clashes are living reflects the political instability of Manipur today. And yet, ethnic warfare is not new to the state or its people, divided mainly between the Meitei, Kuki-Zo and the Naga communities. Victims of the ongoing violence, Kuki-Zo have remained adamant against reconciliation with the Meiteis. All 10 Kuki-Zo MLAs in Manipur assembly have pushed for “separate administration” of tribal areas and the demand echoes in every Kuki-Zo home.

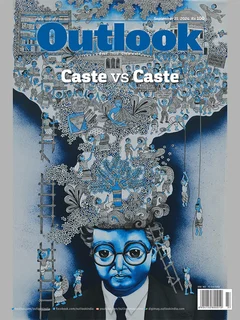

Against this backdrop, the recent Supreme Court’s verdict on sub-categorisation of Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs), allowing state governments to sub-classify these communities to promote affirmative action, has left many in the region concerned.

The concerns are not unfounded. Since the start of the conflict, the N Biren Singh government’s role has been highlighted multiple times, not just for his inability to stop the violence, but for his and Manipur Police’s alleged role in instigating and perpetuating systematic attacks against the Kuki-Zo community. His “anti-Kuki” political tirades and policies predate the current conflict and conform to a pattern of persecution and vilification of Kukis as “Myanmarese immigrants”, “poppy cultivators” and “militants”. The chief minister is alleged to have direct links with armed “socio-cultural” Meitei nationalist groups like the Arambai Tenggol, accused in nearly all cases of violence, arson, looting and sexual assault against Kuki-Zo since May 2 last year. The recent audio tapes released by The Wire also point toward his alleged involvement in the communal violence.

With Manipur trifurcated between Meiteis, Kuki-Zo and Nagas, sub-categorisation and “creamy layer” debates among tribals could open a Pandora’s Box

Accusing Singh of “orchestrating a genocide against the Kuki-Zo minority to grab tribal land”, activist Lamminlun Singsit says the community finds it hard to trust the discretion of the state government in deciding who is “backward” or “forward”. After all, it was a demand for tribal status by the socio-politically dominant Meiteis that became a catalyst for the ethnic clashes unfolding since last year, leaving over 220 people dead and thousands displaced. In January, the Manipur government announced the formation of a committee comprising all tribal communities to deliberate on the demand for deletion/inclusion of nomadic Chin-Kuki from the state’s ST list, provoking a sharp response from Kuki-Zo, who at present, have 10 of 60 seats in the Manipur Assembly.

“The government is run by Meiteis. How can we trust them? Will they guarantee that they will not use sub-categorisation as a tool against the tribes?” Singsit, who is the general secretary of the Committee on Tribal Unity (COTU), Kangpokpi, asks: “At present, all tribal communities in Manipur (other than the Nagas) are united and organised under the banner of Kuki-Zo, and we want separate administration for our regions in Kangpokpi, Churachandpur and Tengnoupal.”

This rather tenuous unity has come after years of inter and intra-tribal rivalry and bloodshed. With Manipur trifurcated between Meiteis, Kuki-Zo and Nagas, sub-categorisation and “creamy layer” debates among tribals could open a Pandora’s Box of past ghosts. “In spirit, sub-categorisation might be a good thing for marginalised communities, but it also has the potential to sow seeds of division within the already ramified tribal societies as found in most parts of the Northeast, including Manipur,” says Singsit.

Lost in Nomenclature

Manipur is home to 34 STs, including Kuki and Naga groups. By the 1950s, when the Kaka Kalelkar Commission arrived in Manipur, both Kuki and Naga communities made concerted efforts to delineate each tribe separately so as to add them to the ST list. However, the loosely-defined criteria led to an exponential growth in the number of scheduled tribes across India—from 225 in 1960 to over 700 at present.

In Manipur, the politics of scheduling is underscored by its complex history of identity assertion, kinship patterns and phenomenological heuristics that remain in flux amid recurrent violence. Soon after Independence, 21 Manipuri tribes, labelled as ‘Kuki’ by the British, formed a organisation called Kuki Company. But the dominance of the Thadous, one of the tribes inside the Kuki umbrella, became a bone of contention and most non-Thadou tribes, branched out, forming the Khul Union. After the rise of the United Naga Council and the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN-IM) in the 1980s, some of the tribes that had been called ‘Old Kuki’ in the British nomenclature, quit the Kuki fold and adopted the Naga political identity. Growing militancy—the seeds of which were sown in the colonial period—and violent clashes between the Kukis and Nagas affected the stability of regions like Churachandpur, home to Zo tribes. Eventually, seven “New Kuki” tribes, including Zou, Vaiphei, Gangte, Ralte Simte, Paite and a collection of smaller tribes other than Thadou rejected the “Kuki” label and decided to adopt the ‘Zomi’ nomenclature. In 1995, the Zomi Re-unification Organisation (ZRO) was formed, along with its armed wing, the Zomi Revolutionary Army (ZRA), explains Churachandpur-based Zo rights activist George Guite, who is also secretary of Kuki State Demand Committee and member of ZRO.

The Kukis, who had their own armed groups like the Kuki National Front (KNF), which is funded by voluntary social taxation, started clashing with the Zomi groups and levying heavier taxes on tribes identifying as Zo. Things came to a head in 1997 when a full-scale conflict broke out between the Kukis and the Paites, one of the dominant groups among the Zo tribes, after KNF operatives massacred Zo civilians in Saikul on the suspicion of being linked with Nagas. The year-long conflict, notes author Th Siamkhum, left over 300 dead and thousands like J’s family displaced. Today, the Kuki Inpi, a civil society organisation named after the system of pre-colonial governance followed by Kuki groups, remains the apex body of Kuki civil society groups and is at the forefront of what an observer in Imphal sardonically called “the Kuki show”.

Hierarchies of Invisibility

A year since the violence, strands of assertion can be seen across the Kuki bastions. In the boarded-up Churachandpur, with higher number of Zo tribes and shared borders with Mizoram and Myanmar, the Zomis have consolidated influence, as can be seen in the banners, flags and posters of ‘Zomaland’ across the region. In Kangpokpi, the writing on the wall is still “Kukiland”. A member of the Kuki Student Organisation (KSO) in Kangpokpi, without wanting to be named, says, “The Union government should accede to the demand for separate administration—the final name will be decided in consultation with all, but it will most likely be Kuki. We are all Kukis.”

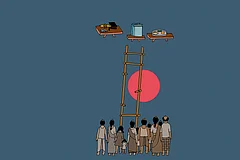

Often listed as “unclassified” or reduced to clans or “sub-tribes” within a tribe, several communities that deserve distinct classification remain unseen.

Others like author and researcher Thongkholal Haokip remain hopeful that “if implemented fairly and using the right criteria, sub-categorisation could prove to be a positive thing for socio-economically and politically deprived groups”. “Every community has its own layers of social division. Among Kukis, the Thadous and the Paites can be considered more advanced,” says Haokip. The dominance of the Thadous is evident from their high degree of political participation in democratic governance. At present, five of the Kuki MLAs from reserved seats are Thadous. Haokip, however, warns against looking at tribes as homogenous groups and a “one-size-fits-all” kind of policies for tribal development, especially in the Northeast. “More Thadous and Paites may have access to development, but that can also be attributed in part to their larger numbers than other tribes. There are many families from both these communities who remain in remote regions with no access to employment, education or healthcare,” he explains.

Caste-Tribe-Continuum

Focusing on inter-tribal politics at an academic or policy level also tends to ignore intra-tribal politics. Often listed as “unclassified” or reduced to clans or “sub-tribes” within a tribe, several communities that deserve distinct classification remain unseen. For example, Saihriem (also called Farhriemh) community, found in Cachar district of Assam’s Barak Valley, has not been accorded ST status since it is less in number and typically considered a clan of the Hmar tribe, under the Kuki umbrella in Manipur. However, the dialect spoken by Saihriem is distinct from the Hmar dialect. Contrarily, Thadou, Paite and Vaiphei are listed as separate tribes in Manipur, despite being culturally and linguistically similar.

Activist and scholar Lal Chand Dhissa from Kullu, Himachal Pradesh, states that the problem arises when academics as well as policymakers fail to differentiate “tribe” and “scheduled tribe”. “A tribe can be any ethnolinguistic or geographically proximate group or grouping of groups. Scheduled tribes need to be based not on myopic criteria like ‘primitiveness’ or exoticism of a tribe, but on their socio-economic, political, geographic and phenomenological status within tribal society,” he says. Dhissa, who belongs to a community of Dalit tribals, has been fighting for constitutional status for the “Scheduled Tribe Dalits”. Due to his efforts, Dailts from tribal communities like Swangla got the right to register for both for SC and ST certificates in 2004. The activist feels that sub-categorisation would be a good idea as it will help highlight the “caste-tribe-continuum”. “In Lahaul, the identity of ‘Lahauli’ is universal and natural to many. But most Hindu groups have been clubbed under Swangla, while most Buddhist groups are considered ‘Bodh’,” he says, adding that the Dalit communities remain invisibalised, often failing to get either caste or tribal benefits.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Academics like Guwahati-based Ngamjahao Kipgen, nevertheless caution that using caste or tribal identity as the basis for inter/intra tribal classifications could lead to disaster. “Instead of cherry picking tribes, the government needs to look at a more holistic form of development. Provide roads in remote regions, make education more accessible. That would automatically work to alleviate the status of communities which often remain on the margins,” says Kipgen. Tinkering with tribal groupings, he warns, could be a risky business, especially in the Northeast where even minor changes can lead to catastrophic events. It’s something that only J and his family know too well.

(This appeared in the print as 'United Indifference')