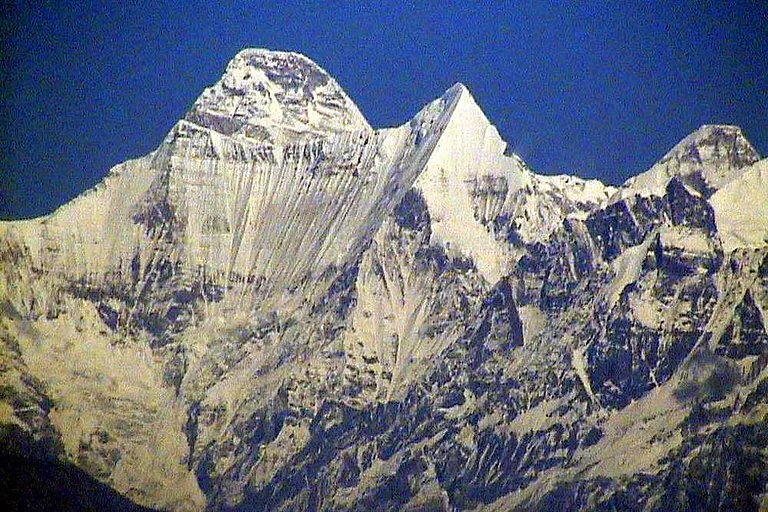

The scene was a study in contrasts. It was a pleasant July afternoon. A gentle breeze was blowing. We were surrounded by stunning Himalayan mountains. And then there was a trail of destruction. Debris was strewn all around. As if an earthquake had just struck.

Very carefully, adjusting our steps on the few stable bricks, we followed Raghu Singh Kunwar, 43, who was taking us to his home down the mountain, a home that once was. We stopped and contemplated when we had to cross a long, crumbling pavement—it was slanted 30 degrees, all set to cave in. It had rained the previous night, making it even more unstable. “This is the only way,” says Kunwar.

It led us to his living room, overlooking the mountains. No roof, no walls; more debris. “I used to have tea sitting next to the window here. There was the kitchen. My wife loved these colourful tiles,” he said, while picking up a broken tile. There were broken pieces of a desktop keyboard, a broken cupboard, a broken almirah, broken crockery … and broken dreams. “I don’t come here often. There are so many memories. It makes me emotional,” he adds, his voice choking. There were other homes around, razed to the ground. There were remains of green and pink walls; walls that were once home.

Kunwar’s dream home was the epicentre of the tragedy that struck Joshimath in Uttarakhand—perched on a hill at an altitude of 6,150 feet—last year. Land subsidence was the term used. Satellite images released by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) showed that the town sank at a pace of 5.4 cm in just 12 days—from December 27, 2022 to January 8, 2023. More than 700 homes developed cracks, many buildings had to be demolished or evacuated, many chose to leave the town.

“There were two hotels here—Hotel Mount View and Hotel Malari Inn. At 2 AM on a cold January night, there was commotion. People said Hotel Mount View was collapsing. We ran for safety. There was a deep crack between the two hotels. By morning, the crack had widened and deepened, and the two hotels were leaning on to each other,” recalls Kunwar.

At first, people assumed there had been an earthquake. “Zameen phatt gayi”, they thought. By morning, they learnt that many homes, roads, hotels and commercial establishments in Joshimath had developed huge cracks. “We had no idea what had happened. Many unfit buildings were demolished. My home was among those. Overnight, we were homeless,” says Kunwar. The family moved to a rented home. The tenants who had been living with them for decades and had become family shifted here and there. It was like a bad dream.

Over the next few weeks, Joshimath turned into a parking lot. National and international media arrived to cover the story—the story of the sinking Himalayan town. Geologists, seismologists, environment and climate experts and scientists arrived too. Many reports, full of jargon incomprehensible to the common people of Joshimath, were published.

But after the last reporter left, Joshimath was a forgotten story. The locals were left alone to pick up the pieces of their lives. Hence, we decided to visit the hill town to tell the forgotten stories. Because these people must not be forgotten—people who are the victims of our quest for mindless development; development they did not ask for. The Himalayan tragedy, after all, has just begun to unravel and its people, mostly those from financially, economically and socially deprived backgrounds, are suffering the most.

Joshimath is strategically important. After the 1962 Indo-China war, an army base was established here. The Indian Army, the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), and the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) are some of the major establishments here.

The town is also a pilgrim hub. Between the 8th and 9th centuries CE, Adi Shankaracharya founded one of the four major mathas in Joshimath. It’s a gateway to Badrinath and Hemkund Sahib. Every winter, the idol of Lord Badrinarayan is brought to the Narsingh temple in Joshimath.

Gradually, Joshimath developed into a tourist town. Those heading to the Valley of Flowers, the Nanda Devi National Park, and the ski slopes of Auli pass through the sleepy town, providing the locals with employment opportunities. Over the years, several multi-coloured hotels, guesthouses, homestays and dharamshalas—many illegally built—sprang up.

Joshimath was thriving until it started sinking.

It didn’t happen suddenly. It had been happening for some time. For years. For decades. Since the 70s. In 1976, a government committee cited deforestation, unplanned construction of buildings, road construction using explosives, inadequate drainage of wastewater, and erosion at the base of Joshimath caused by the Dhauliganga and Alaknanda rivers as the main causes of land subsidence.

In 2006, the construction of the head race tunnel for the Tapovan-Vishnugad plant—a 520 MW hydroelectric project by NTPC on the Dhauliganga river—started. After the tunnel received environmental clearance in 2007, the Joshimath Bachao Sangharsh Samiti (JBSS), a group of local activists who first raised the land subsidence issue in the hill town, wrote to the president, citing instances of slope destabilisation. But excavations for the 12.25-km tunnel through the Joshimath mountain continued. About 8.5 km of the tunnel was excavated with a tunnel boring machine and the remaining 4 km by drilling and blasting. The boring machine got trapped inside the tunnel thrice—in December 2009, February 2012, and October 2012.

While NTPC argues that the tunnel lies at a horizontal distance of around one km away from the town, the JBSS asserts that a bypass tunnel was excavated with explosives right below the town to rescue the boring machine that had been trapped inside the main tunnel.

“Natural disasters are unavoidable. But what’s happening in Joshimath now seems more manmade than natural,” says Kunwar. In hush-hush tones, the locals talk about the company, the tunnel and the blasting.

“We never asked for these all-weather roads or power projects,” says Atul Sati, the convenor of the JBSS. “Our requirements were schools and hospitals. Instead, these projects came up. Our mountains were drilled, and trees were chopped. This went on for years. And what’s the end result? The all-weather road caves in now and then. There is no electricity in Joshimath for hours on a daily basis,” he adds.

As we moved around the hill town, we came across many homes with a giant red cross mark on the doors or the compound walls. These have been labelled by the authorities as dangerous. After last year’s sinking tragedy, many people had to leave their homes, and some moved into rented accommodation. But some had no option but to live in their crumbling houses.

A flight of about 100 steps carved out of mountain stones took us downwards, to the ancestral house of Dinesh Kumar, a daily wager, and Satashri Devi. There was a government notice pasted on the main door. It said the house was in the danger zone and must be evacuated with immediate effect. That was last year. But the couple continued to live here. The government hasn’t provided them with any alternative accommodation or compensation, and they can’t afford to pay the rent.

The main room had developed a huge crack through which a piece of sky was visible. There was one cot in the room and on one chair, framed photos of their two young sons. Both died in two separate accidents. “The authorities say we must move out of this house. This is where my two sons died. There are memories. I will move out only after my death,” says Satashri Devi. The pressure cooker whistle went off. Rice was being cooked. She offered us tea. The kitchen had numerous small cracks through which afternoon sunlight was peering in. Don’t you feel scared? “Yes. At night. And when it rains. There was no one to guide me regarding rehabilitation and compensation. So, we continued to live here,” says her husband.

In the main bazaar area, Brajesh Singh, the owner of New Star restaurant, while peeling boiled potatoes to make aloo parathas, complained about the negative publicity Joshimath received last year. “This year, tourists are giving the hill town a miss. The pilgrims are straightway going to Badrinath and Hemkund Sahib. The ropeway starting from Joshimath to the skiing destination of Auli was a major tourist attraction. But it had to be stopped last year after cracks developed on one of the pillars. There is no incentive for the tourists to stop here. Our economy depends on them,” says Singh.

Joshimath saw as many as 4.9 lakh visitors in 2019 and over 1.65 lakh in 2021. People were hoping for an uptick in business after the pandemic, but 2023 happened.

The hill town was developed to cater to tourists and pilgrims, but Singh says this development was not sustainable. “Many people have built multistorey homes and hotels by flouting norms,” Singh says.

The fragile slopes of Joshimath could not handle the increased burden of illegal structures, local residents and incoming tourists.

“The norms of development must be different for different regions. What works for Ahmedabad may not work for Joshimath. For any development work to be carried out in the Himalayan region, the geology and fragility of these mountains must be taken into consideration,” says Sati.

Trails of destructive development were visible as we moved upwards to Raini village, 24 km from Joshimath. On February 7, 2021, the residents of Raini witnessed a calamity of epic proportions. The Tapovan-Raini region was hit by a sudden flood after a glacier broke off and slid down the valley. The glacier burst caused massive flooding in the Dhauliganga and Alaknanda rivers. The violent surge swept away the Rishiganga Hydro Electric Project. More than 200 people died.

“First, there was a rumbling sound, then a strong wind blew and within minutes we saw water gushing towards us in full force,” recalls Asha Devi, a resident of Raini.

Many people were working in the tunnel at the project site when the tragedy struck and could not run. Some bodies got swept away and were never found; some were discovered months later. In fact, one body was found trapped in the tunnel around a year after the tragedy.

The geologists who surveyed the region after the glacier burst declared that the mountain slope on which Raini village stood was highly unstable. They declared Raini unfit and recommended rehabilitation of the village.

Asha Devi led us to Darbar Singh Rana’s home. His 32-year-old son Yashpal got swept away in 2021. He was herding his sheep near the river when the flash floods hit. His body was found three days later.

His wife is still in a state of shock and does not interact with anybody, let alone strangers. Her two children were playing with a broken toy car in the courtyard. A family member took us to the roof where Rana was waiting for us. He was looking in the direction of the Rishiganga-Tapovan tragedy site; the site that killed his son. The fact that he gets to see the site daily is not letting him get any closure. His emotional state was difficult to tell, but he agreed to be interviewed.

“Mountains have become hollow because of construction. They are not able to stop the flowing water. When a glacier bursts, this water comes gushing down with force. Scientists are saying there are many such glaciers on the top that are vulnerable. We feel scared, especially when it rains,” he says.

Further up, at an altitude of 8,000 feet above sea level, the people of Auli—which happens to be Asia’s longest skiing slope—were disappointed about less snowfall over the past two-three years. Now it snows only in December and this snow is not powder snow; it’s filled with water and melts sooner. “Earlier, we could see glaciers on the entire Lower Himalayan range that is visible from here. Not many people used to visit Auli then. But now lakhs of people come to Auli and go beyond for trekking. Increased tourism activities led to development. Because of these changes, Auli is getting warmer and there is less snow,” says Shyam Pandey, 70, who was sending next to an artificial lake that has been created in Auli to create artificial snow so that guests from across the globe, who arrive in the town in the winter season to participate in the winter games and skiing festival, don’t go back disappointed.

Another instance of destructive development in the region that made national and international headlines was the partial collapse of the Silkyara-Barkot tunnel in November last year. It resulted in the entrapment of 41 workers for 17 days before their successful rescue. The 4.5 km-long tunnel, the longest on the Char Dham all-weather road project, had encountered a series of similar incidents in the past five years.

The Char Dham project is a road widening project to ensure all-weather connectivity among the four shrines—Yamunotri, Gangotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath. The Rs 12,000 crore project was inaugurated by the prime minister in 2016.

According to the current rules, a linear project less than 100 km in length does not require environmental impact assessment. The 900-km-long project was broken down into 53 separate projects to avoid the need to do an environmental impact assessment. The issue was taken to the courts; it went to the National Green Tribunal and then to the Supreme Court. The stakeholders concerned kept delaying and dodging because they did not want the environmental impact assessment to happen.

In 2019, the Supreme Court appointed Ravi Chopra, an environmentalist based in Uttarakhand who is renowned for his dedicated efforts to preserve natural resources within the Himalayan region, as chair of a committee to review the controversial Char Dham highway construction project. He resigned after construction proceeded despite the committee’s findings that the project could pose significant risks to the ecologically fragile region.

Not just in Uttarakhand, mindless construction is causing destruction across the entire Himalayan range spread across 2,500 km and 13 states. “We have done enormous harm to the fragile Himalayan region by building roads, dams and railways,” says Chopra. “We have to be extremely mindful while taking up development work in the Himalayas. Before initiating any project, we need to do an adequate prior investigation of the geology, the ecology and the culture of the local society and we definitely need to recognise the limits that nature imposes,” he adds.

Giving an example of the nature of violations, Chopra said that until recently there was a standard that while making roads, one does not cut slopes that are more than 30 degrees. Yet, this basic norm has been flouted time and again.

“Development work in the eco-sensitive Himalayan region zone cannot be carried out in a similar manner as in any other part of the country. Himalayan glaciers are our water towers. They are the precious assets we have, and we must protect them,” says Hridayesh Joshi, who writes extensively on environment and climate issues.

In Himachal Pradesh, too, despite the fragile geography, relentless development has been carried out to accommodate pilgrims, hydropower and road projects, and tourists. Scientists and geologists blame unscientific and illegal construction, slope-cutting and lack of proper drainage systems for the recent manmade disasters. The region’s 2,500 glaciers are retreating at an alarming pace due to increasingly warm temperatures, exacerbating rain-related incidents.

In November 2023, the 60-metre-high concrete faced rock-fill dam of the 1,200 MW Teesta Stage III hydropower project in Chungthang, North Sikkim, was breached; the powerhouse was submerged and the bridge connecting the powerhouse washed away by a glacial lake outburst flood. Civil society and activists had warned as early as 2005 that glacial lake flood was a possibility, but the project got clearance in 2006.

Why is the government ignoring the recommendations of informed policymakers and going ahead with these projects? “There are very strong lobbies. There is commercial interest combined with the personal interest of politicians and bureaucrats that pushes ahead with this kind of mindless development. What we need is mindful development. We need to build roads because people need them. But we can’t be building roads by flouting norms,” says Chopra.

While development is imperative, what should be done to ensure that such development activities do not happen at the cost of the suffering of people? “We will have to rethink the model of development. Development should also contribute to the region, and it has to be sustainable and equity-driven. Joshimath, for instance, is a para-glacial zone. As per rough estimates, projects worth Rs 12,000 crore have been initiated in Joshimath. They are still ongoing. Many of these projects have been hit by natural disasters like landslides or floods. So, the cost keeps going up. How is this feasible?” asks Joshi.

While Satyapraksah Dimri, the priest of Narsingh temple in Joshimath, feels after what happened last year, any development work in the hills will have to be carried out with utmost precaution in the future, Ishwarpriyanand from the Adi Shankaracharya math believes the Almighty will protect the hill town from any disasters, natural or manmade.

But after last year, the common people in the hill town have been living in a perpetual fear that something terrible is going to happen. They tend to believe the baseless rumours that are doing the rounds these days. Standing next to her footwear stall in the main bazaar area, Savitri Devi, who has been living in Joshimath for four decades, says: “They are saying the lake on the top of Auli is filled to the brim. One heavy rain and water will gush out of it and the entire town will get washed away. When it rains, especially at night, I wake up and pray to God to protect all of us.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Swati Subhedar in Joshimath, Raini, Auli

(This appeared in print as 'You Gave Me a Mountain')