In Mumbai’s twin city, another bursting-at-its-seams megapolis, Thane, a departed leader’s legacy is at the heart of an interesting electoral face-off.

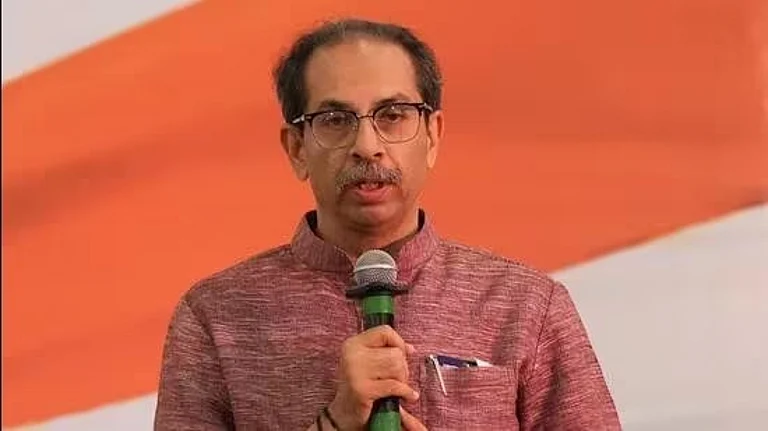

Photos of the brooding-eyed and bearded Anand Dighe, a former Sena strongman, stare from rival poll banners featuring both Chief Minister Eknath Shinde, the current head of the ‘original’ Shiv Sena, and his main electoral contender, Kedar, Dighe’s 44-year-old nephew, who is contesting from the Shiv Sena (Uddhav Balasaheb Thackeray) faction.

The two are vying for control of the Kopari-Pachpakhadi constituency, a traditional stronghold of middle-class Maharashtrian families, including residents of old gaothan areas, emerging high-rises, and slum settlements—and, of course, for Dighe’s political legacy. Dighe was a guru and Shinde his bhakt, while Kedar is eager to tap into his late uncle’s social and political legacy.

“I don’t need to release two movies to showcase my relationship with Dighe saheb. He is my uncle and I’ve performed his last rites,” Kedar (42) says, mentioning Dighe’s untimely death in 2001. The legacy of the late Anand Dighe has taken centre-stage in Marathi cinema over the past few years, marked by the release of a two-part biopic. The first film, Dharmaveer, released in 2022 just before Shinde’s rebellion from the Shiv Sena, was followed by its sequel, Dharmaveer: Mukkam Post Thane, launched ahead of the upcoming assembly polls. Both films depict Dighe’s life journey and position Shinde as his rightful political heir.

“Shinde may claim to be Dighe’s political heir, but this decision has to be made by the people,” Kedar remarks, adding that the CM has been misusing Dighe’s name and photos in order to promote himself.

Shinde has been an MLA from the Kopari-Pachpakhadi constituency three times since 2009. He served as Thane’s guardian minister and was a local civic body corporator, starting as a rookie Sena worker in the 80s under Dighe’s guidance. Kedar, a former software analyst, left his SAP job to join Sena full-time in 2010. He led the party’s youth wing in Thane and is now its district in-charge.

Kedar is unlikely to pull off a major upset in the contest, which is increasingly being seen as a one-sided battle.

Kedar says he was prepared to take on a heavyweight like Shinde since 2022, the year Shinde rebelled and split the Shiv Sena into two factions. “I did not agree with many actions of Shinde, the way he defined Dighe Saheb’s values and principles, his definition of Hindutva. I met Uddhav Saheb and asked for the responsibility of the Thane region, and the party decided to give me a ticket.”

His nomination has energised the small group of Dighe loyalists in Thane who have remained with Thackeray’s Sena. Former corporator and women’s wing leader Rekha Khopkar enthusiastically backs Kedar’s campaign. “We only want to see Shinde’s defeat. He betrayed us; he is a traitor.”

Maruti Repe, Shiv Sena (UBT) shakha pramukh (branch head) from Thane’s Wagle Estate area, is another old timer supporting him. “During public interactions, it is clear to us that people are not happy with the Shinde government. They are realising that the common people are being taken for a ride with freebies and cash allowances. They want change.”

After Anand Dighe, the Shiv Sena in the Thane region grew under Shinde’s leadership. Following the split, most of the party’s cadre and functionaries joined his faction. Repe claims those with Shinde are opportunistic Sena workers and ‘contractors’ who hopped on to his side for sake of their business interests. “The true Sainiks are still with Thackeray saheb,” he adds.

A week before voting, both candidates’ campaigns appear sluggish. As Shiv Sena’s lead campaigner, Shinde is occupied with rallies supporting his party’s 85 candidates across Maharashtra. Shinde’s Sena candidates will face-off directly against Sena (UBT) in 51 constituencies, including Kopar-Pachpakhadi. Shinde’s trusted aide, Sena MP Naresh Mhaske, is leading the ground campaign in Kopari-Pachpakhadi. He highlights Shinde’s achievements as chief minister, focusing on welfare schemes for the elderly and women, such as free bus rides, the Ladki Bahin Scheme with a monthly allowance of Rs 1,500 and the distribution of three free gas cylinders. Mhaske recently won a landslide victory in the Lok Sabha elections from Thane, defeating Sena (UBT) candidate Rajan Vichare by over two lakh votes.

At the party’s office in Wagle Estate, a former industrial area now home to a residential settlement of chawls, slums, and dilapidated buildings, Kedar is surrounded by a handful of Sena loyalists preparing voters’ lists for his campaign. Despite it being his first big electoral fight and having started his ground campaign only a fortnight ago, he doesn’t appear tense or anxious. “The CM should show us one big project that he has launched in the Kopari-Pachpakhadi area in the last 15 years. The wide roads and beautification projects look good from the outside, but this has not made any difference in the lives of common people. They are all living in appalling conditions,” Kedar says. His campaign is focused on improving basic infrastructure, upgrading municipal schools, launching super-speciality hospitals, reviving stalled cluster redevelopment of old chawls and closing down a nearby dumping ground.

According to political observers, Kedar is unlikely to pull off a major upset in the contest, which is increasingly being seen as a one-sided battle. Besides the two Shiv Sena factions, Raj Thackeray’s Maharashtra Navnirman Sena is also in the fray with its candidate, Ashish Jadhav, making the polls in Kopari-Pachpakhadi a slugfest between three Sena outfits.

Thane-based journalist Abhay Deshpande, who has closely followed Sena’s politics in the region, says there is likely to be a division of the traditional Marathi vote bank among the three Senas. However, Shinde, he maintains, has a clear edge over his opponents. “He has held strong control over the party and its cadre in the city. Plus, being a CM, he has more advantage. People are likely to choose him as a trusted and safe option over other party candidates,” Deshpande says. In the case of Kedar, he adds, beyond being Anand Dighe’s nephew, he doesn’t have a separate identity, nor is he too active in the social or political field.

The release of the twin Dharamveer movies has sparked curiosity about a potential duel between Dighe and Shinde. While the two are being positioned in a contest over Dighe’s legacy, Deshpande believes that, beyond the emotional undercurrent, the narrative doesn’t hold much sway among common voters. Dighe was a powerful figure in the 80s and 90s when Thane was an emerging city, living on the margins of law. A respected and feared Sena leader, he delivered swift justice and resolved social issues through his kangaroo courts. His politics, which combined religious nationalism with social work, made him popular among Marathi locals and youth. Many of those he mentored went on to become senior leaders and ministers within the Sena.

The rapid development of Thane in recent decades with plush-gated residential colonies, malls and the steady immigration of a non-Maharashtrian workforce has, however, transformed the city into a cosmopolitan metro.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The younger generation of Thanekars has not even seen Dighe, Deshpande points out. “Dighe is relevant only because of Shinde’s assertion that he was his spiritual mentor and to differentiate his faction of Sena from Thackeray’s Sena.”

(This appeared in the print as 'Bhakt Versus Blood')