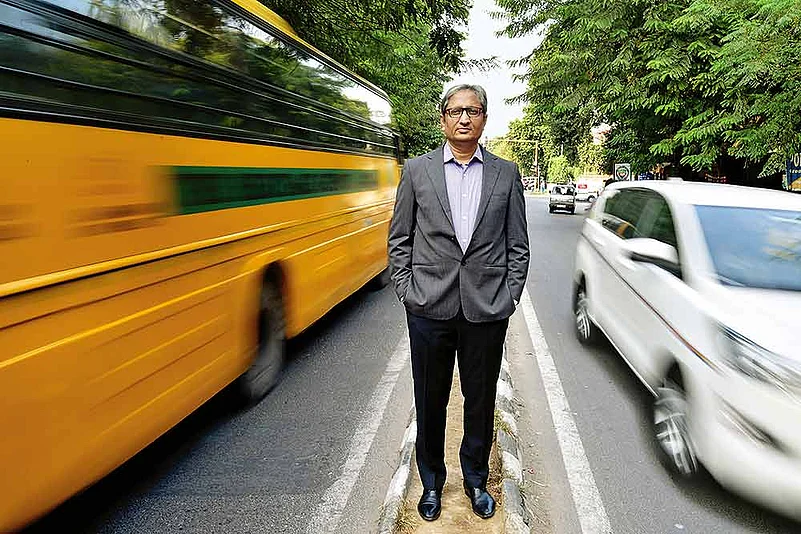

Sitting above news crawlers and tickers, within the confines of the TV screen, Ravish Kumar appears an average man, belying his height and physique. Kumar, 47, is one of the country’s foremost news anchors and hosts NDTV India’s flagship show, Prime Time. His Facebook page alone has over 1.4 million followers. The anchor is loved and reviled with almost equal ferocity. Fan mail and abuse, at times even life threats, fly at him frequently.

Clad in a black T-shirt and track pants, he is sitting in his living room one fine morning, glancing at the newspaper, his grey hair still slick from the bath. As his gaze reaches the headline, ‘No slowdown, say Amazon and Flipkart’, he emits a sigh, “Achchha bhai, nahin hoga phir (All right, if you say so),” then sips from the glass of chirayta (a herb) water sitting next to him. Keeps the tummy fixed, he says.

His three-bedroom apartment is full of life—stained sofas, wind chimes, a refrigerator adorned with fridge magnets, framed photos of puffy newborns, plaques and books. Phone in hand, Kumar scrolls through his Twitter and Facebook timelines, before going through the messages. His phone number is widely available and at times becomes the bane of his existence. But it also helps him keep an ear to the ground.

“Sir, I am big fan of yours. I am coming from Patna to meet you. All I want is to hug you for two minutes and cry,” he reads out a message on his phone. A request for a two-minute meeting seems harmless, unless there are 200 of them pouring in everyday. The doorbell rings and the domestic help attends to the door. “There’s a carpenter,” she says. “Carpenter? I did not call any. Ask her (his wife) if she placed a request for one,” Kumar’s voice is soaked with suspicion. His eyes do not leave the entrance until the help confirms that his wife had indeed called the carpenter. The death threats keep him constantly on his guard. Between this moment and that, between a demigod status and a perennial scare, lives Ravish Kumar.

He drives an eight-year-old car that has never failed him, he says, and doesn’t want a new one on loan at least. “Loan le ke herogiri karna theek nahin lagta (I’m not for living a lavish lifestyle supported by EMIs),” he adds. A guard in charcoal safari-suit is riding shotgun. After the Delhi police rescinded his security in September this year his office arranged private security for him.

Bob Dylan is a favourite of Kumar. You must listen to this one, he says, and plays Blowin’ in the Wind. He hums to it, tapping his fingers on the steering wheel. The elevated view from a flyover pushes him into a more reflective mode. “When we had time, this city seemed so beautiful. Now it looks like one huge office,” he says. “If this is how life’s meant to be, then the concept of homes must be abolished. Everybody should be given compartments in the office.”

A native of Motihari in Bihar, Kumar did his schooling in Patna before migrating to Delhi in the early nineties for higher studies, and subsequently work. The conversation inevitably wheels towards the state of journalism in the country. “It’s so hurtful. The profession to which we gave our lives has come to such a sorry state,” he laments, “Some Modi supporters call me a traitor for my criticism of the government. Believe me, these people are going to need independent media the most in future. Because when they’ll face real issues and ask the godi media to raise them, they’ll be shooed away. And by god, there’ll be only a few who have loved this country as much as I do.”

Kumar wants to be remembered as somebody who kept walking. “And while I’m alive, I’d like to live with fewer things around,” he says. The significance of fewer things is realised when you walk into the yoga centre that Kumar visits everyday. The room is bare, except for a mat placed alongside a wall—his daily yoga sesions lasts an hour.

Kumar has spent his entire journalistic career, spanning almost a quarter of a century, at NDTV. He doesn’t say what he feels for NDTV, but when he’s there it seems he’s in his natural habitat. The ease in his demeanour is evident. People don’t throng to look at him, or ask for selfies here. His chamber is crouched under stairs, towards the corner of a floor. He shares it with two colleagues from his team. About 50 postcards of fan mail wait at his desk. “Ye return hai boss (This is the return for your work),” he tells his team.

One person has written requesting an autograph; he has enclosed a blank envelope with address and stamp on it. One person from Jharkhand has sent an Urdu couplet. Some have sent fervent congratulations for the Ramon Magsaysay award he was feted with recently. There are other letters too. People from far-off places have written about issues ranging from power cuts to poor roads to recruitment. Meanwhile, a bunch of people from Old Delhi is visiting him, and insists that he joins them for a sumptuous dinner someday. He refuses politely. “Dinners, weddings, birthdays, people want me to come for all kinds of events.”

Around 3 pm, he steps up a gear and starts handing out directions to his team, get-me-this, get-me-that. His tone gets a notch sterner and more serious, “I want the experience of protesters, not their issue, stay focused.” The day’s Prime Time will be on citizens making hashtags trend on Twitter as a means of protest. Kumar is making calls, filtering relevant messages on his WhatsApp chat, and telling protesters to send videos.

In times of resource-strapped media functioning—news organisations are increasingly cutting down on reporters and travel expenses—Kumar relies on subjects pitching in. Once the story’s wireframe is ready, he starts writing down the script of his show, in Devanagri. Slouched in his office chair in the cramped office, he begins with the words “Namaskar, main Ravish Kumar …”, words that have attained almost a scriptural dimension, given the profound resonance and immense character they’ve found among a large section of Indians.

About 15 minutes before the clock strikes nine, he rises from his seat and tidies his desk—tears several papers, stacks the ones to retain, arranges the books in a neat pile, and puts his belongings into his bag. As he puts a plaque presented by colleagues in the bag, he’s reminded of his daughter’s warnings, “She told me to not bring more items to the house. I’m going to get an earful.”

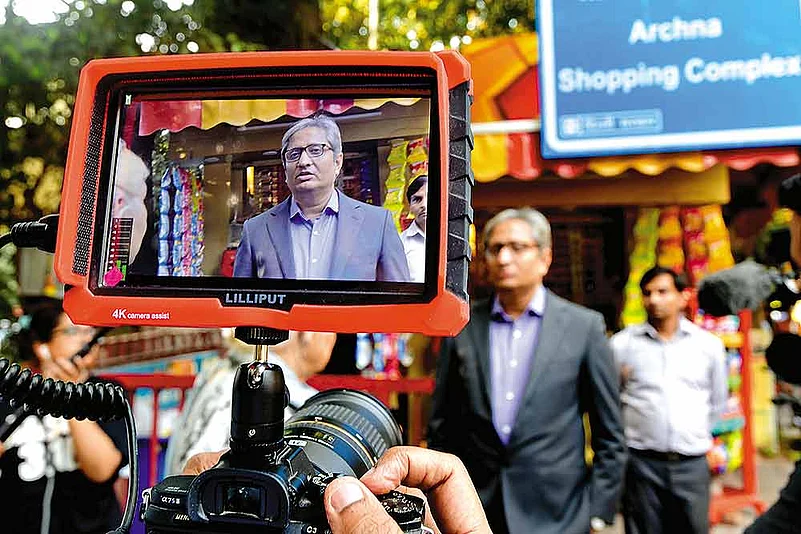

The studio is on another floor. Inside, it’s cold and quiet. About half-a-dozen cameras stand mounted on heavy tripods. He takes the seat behind the arc-shaped white and purple desk, plugs the earpiece, and exchanges pleasantries with those from the production desk.

Once the camera is rolling, the cameraperson revolves away from the device and starts watching the show on a mute television set in the studio. Once again, the tall journalist has been dwarfed by the screen and shrunk by the crawlers and the tickers.

Ravish Kumar is what the screen makes him: it is what reduces him; it is what enlarges him.

Also Read: