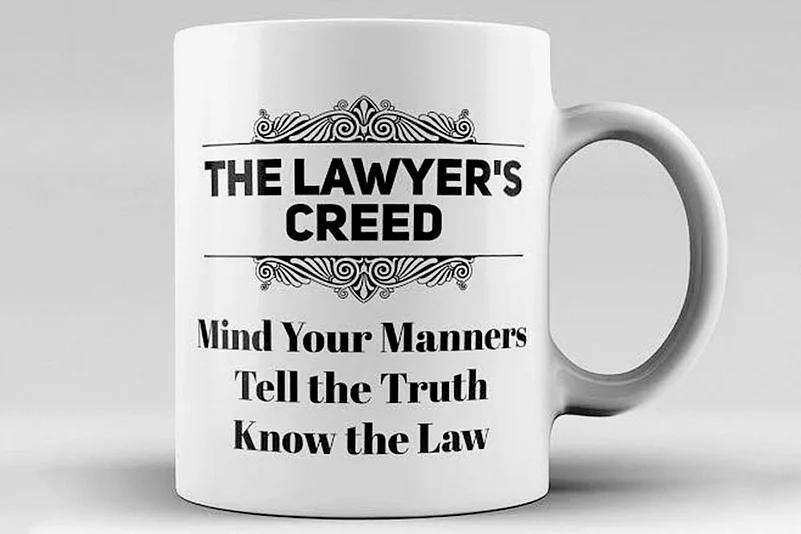

Indians largely tend to shy away from the very idea of litigation. The tales told by those who see it up close will not encourage the rest: inordinate delays, multiple appearances, and the whole bureaucratic tangle starting from the filing of a petition until the final judgment. Enough to leave a lay person intimidated. But while navigating the judicial process is a harrowing experience in itself, there are more material reasons that would dissuade potential litigants from approaching the courts: the state of court infrastructure.

Anyone who has visited a public institution can testify how infrastructure plays a key role in ensuring the quality of service delivery. Courts are no exception. We collected data in a nationwide survey of 665 district courts, including feedback from 6,650 litigants, to put together evidence on the quality of India’s judicial infrastructure. The conclusion is clear: our courts need large-scale improvements to make them more welcoming, accessible and purpose-driven. Here, we chalk out how a day in court for a litigant looks like in most parts of India using this primary data. A handful of readers who have already encountered the system would empathise, but for the majority, who have never had occasion to visit a district court in India, this could be an eye-opener.

Navigation

‘Approaching a court’ requires, literally, getting there. A well-networked, economical, accessible public transport system is essential. The better part: about 80 per cent of India’s district court complexes are accessible via public transport, including buses. (Tripura, Sikkim, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Gujarat, West Bengal, Bihar, Nagaland, J&K and Odisha are among the worst performers here.) For those using private vehicles, 81 per cent of these complexes have designated parking facilities. This is not trivial: of all litigants interviewed, less than half (43 per cent) relied on public transport to reach their designated courts. This prompts the question: doesn’t difficulty of access and/or last-mile connectivity itself make justice, literally, more remote?

Things do not improve after you reach: finding one’s way within a court complex can be daunting for a newcomer. Only 133 out of 665 district courts (or 23 per cent) have guide maps at the entry point, and only 300 have helpdesks. Guide maps include signages that direct a person to important areas of the complex: courtrooms, the registry, the filing department, the canteen, waiting areas, the fire escape, and so on. Daily users such as advocates, court staff and judges are familiar with all that, but a new user will almost certainly be lost in the absence of proper signage. Ideally, there should be signages in multiple languages, including the local language and English. A helpdesk would be a welcome substitute/addition to signages, but only about half the complexes have them. Larger states performed especially poorly on this metric. In West Bengal, not even one court complex had guide maps, and only one had a helpdesk; in Rajasthan, only three out of 35 had guide maps and 6/35 had helpdesks; in UP, only 6/74 had guide maps or helpdesks; Bihar, Jharkhand and Maharashtra fare low on navigation support too. Chandigarh, Kerala and Delhi were the best.

The corridors and halls of court complexes tend to be overcrowded with litigants, advocates, police personnel et al—there are limited or no designated waiting areas and related facilities for this mass of humanity. Only a little over half the court complexes surveyed (361/665) had waiting areas. Large states failed on this count too, with Bihar (6/38), Rajasthan (5/35) and West Bengal (6/23) ranking the lowest. About 4,602 litigants (69 per cent of those surveyed) testified to this abysmal state of infrastructure, with even basic seating not available.

Hygiene

Our courts perform especially poorly here. Shockingly, 100 court complexes around India do not even have washrooms for women. Andhra Pradesh (9/13), Odisha (18/30), Rajasthan (10/35) and Assam (16/27) were the worst offenders. It is possible that female court staff has access to some facilities, but surveyors could not locate facilities designated for public use. Where present, they were often not USAble, unclean and/or without essential facilities like running water. Among courts that had gender-segregated washrooms, only 266 were fully functioning with good upkeep. Goa, Jharkhand, UP and Mizoram had the least number of courts with functional washrooms. Almost half the surveyed litigants complained about lack of running water, then flush facility and liquid soap. Imagine the plight of a litigant with no access to good hygienic facilities while waiting long hours for a case to be called up. Ambitious schemes such as Swachh Nyayalayas (and Swachh Bharat) clearly have a long way to go.

Inclusivity

All kinds of people access courts, including persons with special needs, such as older litigants, persons with disabilities, pregnant women, and so on. Any institution that seeks to be accessible to a diverse audience must be necessarily prepared to accommodate, and make comfortable, everyone. This means, for example, having basic features such as ramps or lifts for persons with motor issues. Only 27 per cent (180/665) had ramps or lifts at the entry and within the courts. A basic feature for visually challenged persons would be notices in Braille, and tactile pavements: only 2 per cent courts had such features. And only 11 per cent (73 courts) had separate washrooms for persons with disabilities. It’s an unfortunate state of affairs for temples of justice that proclaim to treat all persons equally. The court complex in Chandigarh stands out as a model in this regard, as one that provides all three facilities.

Beyond barrier-free access, court complexes must also have other facilities: ATMs, bank branches, canteens, first-aid services, police booths, post offices, notaries, stamp vendors, typists, oath commissioners and photocopiers. Only 39 per cent courts had all these facilities within the complex or in the vicinity.

Overall, the data paints a deplorable picture. Inter alia, it reveals that eastern states—Bihar, Manipur, Nagaland, West Bengal, Jharkhand—are performing poorly (Meghalaya is an outlier, comparing with Chandigarh, Delhi and Kerala). Detailed statistics can be found in the report, Building Better Courts (2019). If district courts are in this state, imagine courts lower down the hierarchy, such as munsiffs’ and judicial magistrates’ courts. This reflects lack of accountability among judicial and executive stakeholders: high court judges in charge of district courts; district and sessions judges; and the departments of law, planning and finance at both the central and state levels. Indian courts have miles and miles to go before they can claim to offer true, accessible and equal justice to all. And for a true reckoning, count physical infrastructure along with more abstract aspects like quality of decision-making and speed of adjudication.

***

The Bare Facts From A Parched, Dry Maze *

- 23% (133 district courts) had guide maps at entry point

- 46% didn’t have helpdesks

- 100 court complexes have no washrooms for women

- 266 court complexes had fully functional washrooms

- 73% court complexes had no ramps for the differently-abled

- 39% court complexes have amenities like canteen, first-aid care, ATMs, photocopiers, police booths and notaries

*Out of 665 district courts surveyed nation-wide Source: Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy

ALSO READ

(The writers authored the report ‘Building Better Courts’ as part of the judicial reforms initiatives at the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. Views expressed are personal.)