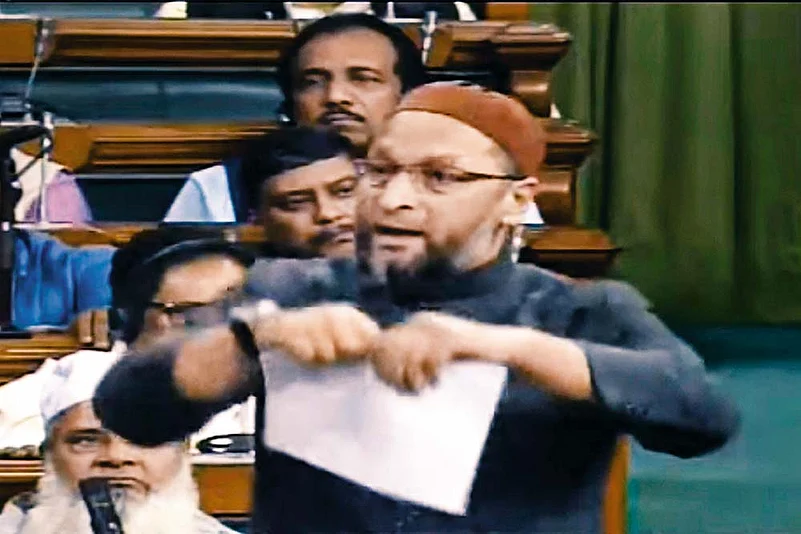

Occasionally, an entity seems to possess power far beyond what’s quantifiable. Of all the chess pieces, for instance, the knight possesses the most intriguing qualities. Despite a limited range, its odd two-and-one, onward-and-sideways dance step allows it mobility in any direction, a certain unpredictability. It’s unique for another reason: it can jump over occupied squares, and so cannot be blockaded. Its potency, therefore, increases as it advances. The figure of a knight is advancing over the Indian political chessboard as we speak. To some who behold it, he appears in shining armour; to others, he seems a disconcerting interloper. Even to the neutral observer—if there is any that can manage neutrality towards the figure of Asaduddin Owaisi—he seems to contain the unknown quality of a googly. His party just hit the headlines by contesting Bihar, winning five assembly seats. And now Bengal looms. Everyone is trying to fathom how this four-time Lok Sabha MP has grown beyond his little island of Hyderabad, to Maharashtra first, and with sallies right into the heartland.

And that’s only one of the ways in which they ask the googly question: which way will it turn next? The answer could be purely territorial—perhaps Uttar Pradesh—or deeply political.On November 10, Diwali came early to the sprawling headquarters of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) at Dar us Salam, Hyderabad. Five seats in the Bihar assembly may seem a slender cache, but in a do-or-die battle, the NDA’s wafer-thin majority nearly gave Owaisi kingmaker status. More than that, it’s what that represented—a national footprint, which the four-time parliamentarian has long been yearning for. Five years after it drew a blank in the state polls, it came almost like a fulfilment of the words of Dalit icon Kanshi Ram, often invoked by Owaisi—that “the first election is meant to be lost, the second is to get noticed and the third is to win”. The signs of a change in Muslim voting patterns were already visible in the 2019 Maharashtra assembly results, where AIMIM made significant gains, garnering two seats and coming second in four more. It was back in 1958 that Asaduddin’s grandfather, Abdul Wahed Owaisi, prefixed the old MIM with an AI—All India—when he took the party’s reins in 1958. It’s taken 62 years, but finally it’s showing the potential to live up to that name. Even if it produces disquiet in several quarters.

ALSO READ: Look Back In Denial

For, the 51-year-old Asaduddin Owaisi is many things to many people. There’s unanimity on only one aspect: he’s suave, dapper, charismatic, razor-sharp, and very articulate. The first thing thrown at the man at the helm of the AIMIM is related to that last bit. That he can perhaps be too articulate, to the point of stridency. In a country where ‘Pakistan’ remains the favourite bugbear, a political Muslim with those qualities evokes only one historical memory. Owaisi, almost inevitably if willy-nilly, courts that analogy: there’s no shortage of those who see in him a sort of djinn of Jinnah, carrying an ‘anti-India’ seed in him. This despite the existence of a video of an event in Pakistan where it is he, among all those present, who gives one of the best possible, most rousing defences of constitutional Indian nationhood. And the fact that it’s entirely on India’s democratic turf that he seeks his game.

ALSO READ: Middle Name Confidence

That’s one reason why, for an increasing number of Muslims, he fills a vital gap in Indian polity. Partly owing to the birth-wound of Partition, we have not had, since Maulana Azad, a truly pan-Indian Muslim leader, a protector figure. Now, Owaisi is no Azad—the latter would today be called a ‘sarkari Mussalman’—but he does speak clearly, unambiguously, on issues that cast others into defensive silence in Modi’s India. On Ayodhya, the Citizenship Amendment Act, or the UAPA. And yet, he stays short of sounding rabid. He uses his training as a barrister to keep his arguments cogent and within the confines of the Constitution. Many among the community, naturally then, respond to his tell-it-as-it-is brand of politics, converting their admiration for his outspokenness into votes. He has been arguing for a decade that non-BJP parties garner Muslim votes, offering them security and promising to save secularism, and quietly ignore their interests once voted to power. And that rings true on many counts. That’s why Owaisi’s senior from Osmania University, Muralidhar Rao, an RSS pracharak, says the “so-called secular parties” are responsible for Owaisi’s political growth. “The vacuum has become an invitation for him to expand to other states,” he says.

Women gather for Eid prayers in Chennai. For many Muslims, Owaisi fills a vital gap in Indian polity.

But there are plenty of troubling penumbral shades beyond that binary. For one, rather than being a secular antithesis of the BJP, there’s a genuine sense in which he offers a mirror image of its right-wing politics, except it is denominationally Muslim. Owaisi reserves his worst criticism for the Sangh ideology but former Organiser editor Seshadri Chari speaks with remarkable candour when he says he sees an identicality. “Owaisi is playing on the insecurities of the Muslims. He has successfully managed to sell this idea to Muslims that the Congress and other parties cannot save them from the ‘BJP-RSS goons’, and he is their only saviour. It is much like what a VHP-Hindutvavaadi fellow will tell the gullible among the Hindus: that only BJP can save them. It works both ways,” Chari tells Outlook.

ALSO READ: Make Space For Three

The next interweaving shade is no less troubling: not every Muslim responds with the same enthusiasm to what he represents. There are many, even beyond the liberal, financially secure sections, who do not see Owaisi as their leader and accuse him of “dividing the community”. For decades, millions of Muslims have sought and found refuge—even if patchy refuge—in umbrella parties that unified them with other communities as equal stakeholders. They did not have to risk bargaining as a separate bloc as long as their interests were preserved. The Congress played this role along with the Left in the old days, and then the post-Mandal parties and the TMC—all of them fulfilled that criterion. As campaign videos from Bihar showed, both as a matter of habit and inclination, many of them would prefer to keep their politics that way. But some of them don’t. The corollary is logical: a split in votes. That’s why he is frequently called “the B-team of the BJP” by the Congress and other political parties, or a ‘vote-katwa’ (vote-cutter) who ends up helping the BJP. They say he does this not only by dividing the secular votes where the AIMIM contests, but by affecting the whole ecology far beyond those seats, offering the perfect bogey for the BJP to effect a counter-mobilisation. In its own spirited defence, the AIMIM points out that it approached the MGB leaders before the Bihar elections and was rebuffed—perhaps because the RJD-Congress underestimated them, or sought to wish away the Owaisi phenomenon. But the underlying dynamics would stay true even if they pooled their votes.

It’s created a lively debate among them. S.T. Hasan, Samajwadi Party MP from Moradabad, who feels the AIMIM plays a “dangerous, disruptive politics” by appealing to a section of the community that’s backward, more orthodox and perhaps even radical, blames the older parties for this. “A Ghulam Nabi Azad or a Salman Khurshid lack the acceptability that Owaisi is trying to tap. The Congress promotes pseudo-Muslims who shy away from taking any strong position on issues relating to minorities and it prefers that an Owaisi or an Azam Khan speak on controversial matters,” he says. Congress leader and former Union minister Tariq Anwar fends that off defensively. “Unfortunately, we are now living in times when even speaking up for the rights of Muslims is promptly given a spin by the BJP,” he rues. “The Congress is a secular, national party and obviously it can’t just appeal to one community. We have to fight Hindu radicals as aggressively as we take on Muslim radicals. Unlike the BJP or AIMIM, we have to take all communities along. Owaisi’s only focus is the Muslim vote, BJP’s focus is just the Hindu vote,” he adds.

ALSO READ: Only The Tall Get Gaud

Is it possible for Muslim political formations to forge a broader alliance with mainstream parties? Indian Union Muslim League leader M.K. Muneer believes so, and cites the Kerala model of the Congress allying with the IUML. “We aren’t saying Owaisi is an agent of BJP. But his present strategy is spoiling the unity of secular forces. The Grand Alliance in Bihar should have taken them along. The Congress should be more lenient,” he says. But the fundamental fact remains that the two sides exist in competition strategically and ideologically.

Mohammed Jawed, Congress MP from Bihar’s Kishanganj, explains the schism by echoing Chari. He says the BJP-RSS and the AIMIM perfectly complement each other, creating a mutually beneficial duality that eats into the secular space. “If you observe the political landscape of the past decade, you’ll see Hindu polarisation isn’t merely about Hindus voting BJP; it’s about radical Hindus being emboldened enough to lynch Muslims without any fear of the law. People like Owaisi feed off this to polarise Muslims.” The rise of the AIMIM is thus a direct corollary to the rise of Hindutva radicalism, and both are a challenge to India’s secular fabric, he says. The Majlis raises issues that are extremely emotive for a section of Muslims with the aim of responding to Hindutva radicals with Islamic radicalism, according to him.

‘Radicalism’, of course, is a word that gets tossed around all too easily these days, but a certain clear-cut leaning to the orthodoxy is undeniable. It’s a game everyone has played—captured in that derisive phrase, ‘appeasement politics’. EMS created the Muslim-majority Malappuram district, the Congress has its infamous Shah Bano episode, and everyone from Mulayam Yadav to Mamata Banerjee tactically backed hardline or orthodox elements. Still, what they did as often myopic political negotiation—while running universalist politics of their own—the AIMIM will do unequivocally. As its formal politics. When it protests the ban on triple talaq, it does not merely argue against the BJP’s questionable political motivations: it could be said to be genuinely, unreservedly batting for a gender-unfree status quo.

This orthodox, Sharia-oriented stance segues onto another flaw not widely acknowledged: caste. Hindutva works on a casteless fantasy only nominally; Hindu society is openly caste-based. Islam, on the other hand, formally admits of no caste—even if the Indian reality is fundamentally structured around it. ‘Muslim politics’ in India has always been led by the dominant Ashraf elite—the pre-Partition League, Congress’s Maulana Azad, the IUML, the Left-leaning cognoscenti and cultural icons. They have had, as it were, a separate, perfumed existence. For the real Muslim masses—drawn from the vast array of old occupational castes--from pastoralists, weavers, dhobis, barbers, oil-pressers and butchers on to the Dalit Pasmandas—the only space left was the benighted pages of the Sachar Commission indices. And yet, one finds Owaisi offering stout resistance to the idea of sub-reservations within the Muslim fold. In his innovative ‘Jai Bhim Jai Meem’ slogan, the ‘Bhim’ is not allowed to colour the ‘Meem’ (Muslim): they are to be watertight. So, even as he strategically pursues social alliances, profiting for instance in Maharashtra by stitching up an alliance with Prakash Ambedkar’s VBA, doubts endure. Mohammad Sajjad, a history professor at AMU, says Owaisi’s vision of “Dalit-Muslim unity is cosmetic. Muslims can’t be treated as a homogenous group and he is ignoring the layers in the community. By doing this, he is equating Dalits as Hindus and Muslims as one unit here. Pasmanda Muslims disapprove of him because of that.”

A collapse of secular politics is implicit in Owaisi’s rise. Not only has India persistently failed its poor Muslims in socio-economic terms, even the old protective cover of politics started fraying under the BJP’s onslaught and persistent taunts. In some senses, it’s a wholesale retreat. On November 12, after Tejashwi Yadav held his first post-results press conference, he faced a barrage of questions on social media for the absence of Muslim leaders on the stage. “There are even rumours that there was a concerted effort by Yadav leaders to defeat Muslim and non-Yadav candidates in the election,” says Prof Sajjad. Manoj K. Jha of RJD refutes these as “cooked-up stories” while refraining from levelling any charges against the AIMIM.

Maharashtra Congress leader Husain Dalwai has perhaps the most damaging story. He says he was asked to campaign in Purnea but had to cancel the plans as the Congress candidate asked him to do so. “I was all set to go and then I received a call. The candidate asked me to cancel my visit as he feared he would lose Hindu votes if I campaign. I was very hurt. The party did not send a single Muslim leader to Bihar. They were asked not to go there,” says Dalwai. His party’s pusillanimity is what’s “pushing Muslims to communal parties”, he feels, asking for a course correction. If the Congress practises soft Hindutva, “how can we make Muslims understand the dangers of parties such as AIMIM?”

What emerges from this complex welter? What does Owaisi’s rise augur for Indian politics? Political commentator Saeed Naqvi doesn’t see a long-term future for him in his present avatar. “He offers some kind of security to Muslims, but the negative is that it consolidates the other side, and they are the majority. Who is stopping Hindutva? Owaisi or not, Hindutva is there.” In a sense, then, Owaisi is a confirmation of the success of Hindutva. Rizwan Qaiser, professor of history and culture at Jamia, too, says Owaisi’s right-wing politics doesn’t offer a solution to the BJP’s majoritarian politics—instead of empowering Muslims, Owaisi is harming them. “Why practise a politics which separates the community from others? The idea is to build bridges,” says Qaiser. He feels Owaisi offers a false sense of security to a community “left to fend for itself”.

Asim Ali of the Centre for Policy Research, Delhi, feels independent Muslim political assertion has its limitations. “The long shadow of Partition had till now circumscribed the limits of Muslim assertion. Unlike Dalits and OBCs, Muslims have shied away from supporting a party or leader from within the community, at least on the national stage. If the AIMIM can make inroads in Bengal and UP, it will mark a fundamentally new phase in Indian politics,” he says. But shunning the mainstream parties may not augur well for Muslims in the long run, he argues. Since the Muslims lack the numerical heft to make a party like the AIMIM a serious contender for power—it can at best act as a pressure group. “The challenge to the BJP will still come from secular parties, and it doesn’t make sense for Muslims to abandon these parties,” says Ali.

Poet-activist Iqra Khilji, while critical of the AIMIM’S stand on caste and gender, is against blaming Muslim voters. “Voting BJP and voting AIMIM are very different acts. In a Hindu-majority country, you don’t merely seek representation through parties like the BJP. You seek vengeance against minorities. The minorities seeking representation is a legitimate cause if somebody believes in that. The AIMIM’s stands and politics can be criticised. But I contest the allegation of counter-radicalisation of the Muslim voter,” she says.

Indeed, all the talk of radicalisation serves to hide the fact that the AIMIM has more strings to its bow. Adnan Farooqui, who teaches political science at Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia, has an interesting take on how the AIMIM rebuilt itself after independence, when the party found itself branded as a communal, anti-India outfit for opposing accession. They did this by primarily going welfarist and pro-people. “For a long time, the party was believed to be a rickshawallah’s party. Elite Muslims didn’t vote AIMIM. They voted Congress. But the vulnerable felt the AIMIM raised issues concerning them,” says Farooqui. After Asaduddin took over in 2008, he has assiduously followed this model—ensuring a stern public accountability system for his lawmakers. At the party HQ’s grounds, AIMIM MLAs are required to be present six days a week, often with Owaisi present to oversee the goings-on, before their constituents. The locals, irrespective of faith or economic station, can walk into this durbar and seek answers on the progress of various public works or for help in personal matters. Owaisi, too, is readily accessible to his voters; often driving around Hyderabad for impromptu conversations with his electorate. Recently, when Hyderabad was ravaged by unseasonal rains and resultant floods, Owaisi was on the streets for hours every day—offering rides to the stranded, overseeing relief work till well past midnight. It’s this governance model that the AIMIM has often showcased when seeking to expand to new territories.

Owaisi with a supporter. AIMIM built its base by going welfarist and pro-people.

If its candidate polled nearly three lakh votes in Kishanganj even in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, locals say it came on the back of AIMIM workers doing a lot of relief work in 2017, when “the worst floods in 100 years” wreaked havoc in the district. Even during this year’s lockdown, the party set up five helplines and arranged for several trains to bring Bihari migrant workers home from Telangana. The party also denies it won merely by polarising votes. “We fielded five Hindu candidates out of 18, even from Muslim-dominated Barari. In fact, we got a sizeable number of Hindu votes in all constituencies. In Kishanganj, we got over 10,000 Hindu votes,” AIMIM youth wing president in Bihar, Aadil Hasan Azad, tells Outlook. And for good reason. Kishanganj is as backward as “Bastar or Kalahandi”, he says, and Owaisi demands special status for the district on the lines of Darjeeling during Parliament debates. “The BJP tries to polarise voters saying Kishanganj would turn into another Bangladesh, the RJD-Congress seeks to instil a sense of fear of the BJP. Away from both of them, we are trying to prepare a blueprint for Seemanchal’s development,” says Azad.

For all that, an edgier face floats just below the surface. Farooqui has written of a “division of labour” between the Owaisi brothers—a dual strategy where Asaduddin presents the party’s reasonable, moderate, national face, and Akbaruddin plays the ‘bad cop’ with incendiary speeches to Muslim audiences and keeping a check on political rivals, often through violence. Asaduddin himself carries a duality—he’s one thing while speaking in English, quite another when speaking in Dakhani to his audiences in Hyderabad, holding them spellbound with humour and politics that’s often borderline. Unlike other Muslim leaders, social media gives him mileage and visibility. “His speeches are circulated mainly on YouTube. He sells. He defies the conventional understanding of a Muslim leader. He wears a sherwani and a long beard and talks fluent English. He may espouse religion, but invokes the vocabulary of the Constitution. Thus, aspirational Muslims find a meeting point of both traditional and modern in him,” says Farooqui.

Given that organic connect with his base, a larger question looms. Can the AIMIM go beyond purely Muslim politics? Why can’t an Owaisi candidate appeal across religions on the basis of a governance model everywhere, like the party did in Kishanganj? Should this be a wake-up call for parties such as the SP and BSP—a call to supplement identity politics with something more? Samajwadi Party (SP) leader Ghanshyam Tiwari does not think so. “The political space created by Owaisi is not because of the work done by him,” he insists. “It’s due to the kind of politics the BJP is playing. The polarised space it creates automatically creates a counter-space for parties like MIM. Our goal is to delegitimise this kind of space.” Despite that purist conviction, the near future could see some realignment of priorities.

Owaisi growing beyond a Muslim base is not a serious possibility, says Qaiser. “Even the name of the party means it’s a formation to unite Muslims. Yes, Owaisi has to evolve in his own ideological and political persuasions. But if he does it, he will lose his core base.” Chari of the RSS doesn’t believe Owaisi can pull it off either. “If he overreaches and tries to become a pan-India leader, beyond the Muslim constituency, on his chosen anti-BJP pole, that will be his nemesis,” he says. Owaisi sometimes seems aware of the perils of over-ambition. All he wants, he says, is just one MLA in every state assembly, who can stand up and talk for the Muslims—doing what the secular parties could not do. But as he presents a uniquely complex challenge to all sides, with his star in the ascendant, we may see some serious evolution in political vocabulary on all sides.