These fragments I have shored against my ruins.

—T.S. Eliot, The Wasteland

In the summer of 2018, I visited Vancouver, a city in the Pacific Northwest of Canada, for an academic conference. Apart from my professional colleagues, Sanskrit scholars from around the world, I knew a few people there: a Tibetan professor of international relations I had long admired, a Japanese painter with whom I had traveled in Ladakh, and an American researcher who had fled New York city for British Columbia along with his Italian wife.

The couple came to fetch me one day from the university campus where I was staying, and took me to a beautiful rocky beach, refreshingly cold and empty except for a large frolicking dog and his human, with a spectacular view of the city in the distance. They told me how the Chinese, Korean and Russian elite parked their money in Vancouver, investing in real estate and buying up apartments in huge condominiums that mushroomed on the hills rising over the icy waters of the North Pacific. Later we went to meet a famous writer and his wife who my friends were close to, and we all had dinner outside in their back garden.

Our host John Vaillant, a handsome energetic Bostonian from a distinguished lineage of scholars, writes fiction and non-fiction about the world as it is today: shot through with social conflict, environmental crisis, large-scale migration and economic collapse. He documents the death-spiral of capitalist modernity, situating himself at a distance, like a hawk in its eyrie—part ethnographer, part journalist, part memoirist, part naturalist. Such men have bookended America, surely. I was awed by his travels and talents, his awards and accolades, and feared I had little to say that might be of interest.

ALSO READ: Total Eclipse Of The Heart

I had lost my mother five months earlier, and had been traveling continuously outside India since then. My husband and I had moved out of our rented flat in a picturesque and historic part of central Delhi, shifted our boxes to my parents’ house, where I had last lived between the ages of 12 and 22, and departed the country for our separate and joint travels.

I avoided returning to claim that house, my inheritance, as an only child with both parents deceased within the preceding three years. A 45-year-old orphan is nevertheless an orphan.

I felt I had no anchor and no compass, and was embarrassed to meet new people in this state of profound disorientation.

***

John and his attractive wife Nora, an anthropologist and potter, had a fascinating house, full of pottery she had made, mementoes from their adventures in the Americas, books, plants, pets, and things belonging to their two children, whom I didn’t meet on that occasion. John pressed me to say more about my life in India, with the effortless and compulsive curiosity of a true reporter. After a glass or two of white wine I found myself saying that I felt as though the world was ending. What sense did it make for me to try and preserve my father’s writings, my mother’s home, their enormous library and sweet dogs and the old furniture I had grown up with?

ALSO READ: ‘Laab’ In The Mountains

Delhi itself was teetering on the edge of destruction, unsustainably overpopulated, catastrophically polluted, and politically dominated by a right-wing regime. My father had been increasingly isolated among his literary peers, his poetry circling upwards into the sky like a lone bird, and eventually vanishing into the bright, uninterrupted light, taking him with it. As his words were chiseled to sharp points, as his baritone voice leaned into silence, his breath stopped. My mother, who loved the earth and all creatures upon it, died, inexplicably, of lung cancer detected too late. I felt certain they would not be reborn, because they had both seemed to step out of the threshold into the purity of void, the infinity of non-existence.

John leaned back on his garden chair, his thick silver hair and strong chin befitting a Hollywood star rather than a prize-winning writer. “The world ends for every generation,” he said. “It is continuously ending and never, in fact, ends.”

I stared at him for too long, as my mind raced over the ruins of the World Wars, concentration camps, Partition, Hiroshima; it flew like a crazed drone over Yugoslavia and Iraq and Syria and Afghanistan; I imagined my grandparents leaving Lahore with their three small daughters in a convoy of army trucks, clutching keys to doors they had locked forever behind them; I followed my young father, his eyebrows bristling and bushy, his face gaunt from the trials of a penurious bachelorhood, leaving Lucknow for Bombay and Bombay for Delhi, never to return, with a tin trunk full of maudlin songs he had composed and love letters he would lose, probably deliberately, so as to reconstruct them again and again from memory as long as he lived.

As the present stood suspended, I was transported back to November 1984, when Delhi turned against its Sikh minority with a ferocity that took many lives, and changed forever those who somehow survived. I remembered Manhattan in September 2001, the abyss of 9/11, that created a before and after even more definitive and wounding than the transition into a new millennium. John, who I had just been introduced to and whose books I hadn’t read, who knew about extinction events and planetary disasters, had uttered a sentence. But it left a deep impression on my mind, and became a talisman, or a prophecy.

***

My mentor Ashis Nandy has written about “lost cities”. Cities may be lost to wars and natural calamities, or because we emigrate elsewhere. Each such loss is, as John Vaillant said that evening, an ending of the world—our world, the world we knew and peopled unthinkingly for as long as it lasted.

I read and re-read the modern authors who best chronicled cities that were lost and worlds that had ended: W.G. Sebald, Orhan Pamuk, Joan Didion, Saadat Hasan Manto, Joseph Roth. My mother had told me several times over the years, how she felt her world shatter when her older sister, my aunt, was widowed at 40. “Our family had been perfect,” she said, “until we lost your uncle. It burst like a soap bubble. I knew it was the beginning of the end.”

Summoning up my neglected scholarly training, I revisited the Sanskrit epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, where fathers and sons, wives and husbands, brothers and friends are sundered, long years are spent in exile, and great kingdoms dissolve in chaos and bloodshed. Even the gods in their flawed human avatars finally bow before the implacable force of mortality. In these long cycles of story, everyone is washed away by the river of time, carried on its relentless spate, to join the nameless ocean where all beings go.

Over the next three years, following that trip to Vancouver, I would sort, clean, box, donate, throw, rearrange, re-purpose, repair, renovate and re-imagine my parents’ house, their possessions, and our possessions. I learnt that we possess nothing, starting with the people we love, our recollections of happier times, and the clocks ticking away inside us. I learnt to give away whatever I could, but I also clung to many things that I ought to have let go. I could not decide if my inheritance was a burden or a gift, a legacy of love or a mountain of karma.

ALSO READ: You Are Making My Grey Glow

In a fog of grief, I cared for the dogs, worshipped the gods, retained the staff, tended the garden, pickled the mangoes, brewed the tea, washed the linens, changed the curtains, served the food, dusted the books and paid the bills exactly as my parents had done for decades. I even tried to stay in touch with their friends and relatives, their neighbours and colleagues, until they started to decline or die, or it otherwise became obvious that we didn’t have much in common apart from my parents, rather, their irreversible absence.

But the more faithfully I preserved or recreated my parents’ world, the clearer it became: that world had ended. Sometimes I sat up from sleep, distinctly hearing the sound of my mother’s laughter, my father’s song, her endearments for the dogs, his for me. Their voices were for a fraction of a moment audible, before lapsing again into the everlasting hush of a broken dream, the screen blank like in a movie theatre after the credits have stopped rolling and the music has ceased to play. Images flickered and faded; substance became shadow.

***

All around this house that was but is no longer my parents’ home, and where we live but with a strange feeling of transience and an eerie sense of lingering in the past, Delhi is becoming a heap of rubble. Thousands of trees have been cut. Entire neighbourhoods have been razed to the ground, and replaced by forests of ugly multi-storey towers. I no longer recognise the familiar routes of my childhood and youth. The rate of change is apocalyptic, hastened along by climate change, unbridled air pollution, and a regnant political ideology that knows only two ways to address history: either through erasure and denial, or through resentment and revenge.

Here in Delhi, my mother gave birth to me, slightly prematurely, at a small hospital near where my parents lived at the time, and my father gave me not one but several names, unable to contain his excitement at the sight of his screaming and hairless offspring. At the crematorium down the road from that hospital, I cremated both my parents one after the other; in the same vicinity, I held memorials and hosted prayer meetings for them. My father’s fatal heart disease and my mother’s terminal lung cancer, both undetected until the last minute, cannot but be a consequence of Delhi’s polluted air.

I went to school, college and university in Delhi. Here I have studied and taught, rebelled and protested, made friends and struggled with enemies. I fell in love in this city, married here, broke hearts, had my own heart broken, set up house, moved house several times, outgrew my parental home and, after nearly 25 years, had to learn new ways of inhabiting it.

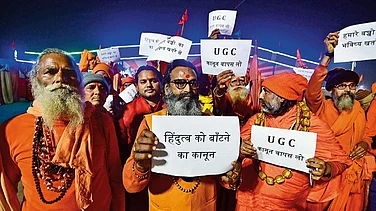

For the past decade I’ve worked in Delhi, at a small, slow but solid centre for advanced research in the social sciences, whose survival also seems increasingly precarious, faced with a hostile dispensation and a claustrophobic atmosphere that routinely discourages and sometimes harshly punishes intellectual inquiry, creative expression and institutional autonomy. The three major public universities of Delhi have been under relentless attack by successive governments, especially after the right-wing assumed power. Newspapers, magazines and television channels headquartered here have either forcibly or voluntarily ceded their editorial independence in the face of relentless political pressure.

Most of 2020 and all of 2021 have been sacrificed to the pandemic, and 2022 threatens to be no different. Through months of this strange hiatus, I have joined hands with about 60 people—historians, architects, lawyers, artists, urban planners, writers, curators, environmentalists and film-makers—all of whom are dismayed and alarmed by the Central Vista Redevelopment, a fantastically expensive project of the central government that will finally drive a stake into the historic heart of Delhi.

ALSO READ: December White

To say that a few of us concerned citizens have “joined hands” would be to suggest that our collective effort might stave off the imminent destruction, dislocation or disfigurement of the Parliament building, the National Museum, the National Archives, the India Gate lawns, the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, and a variety of other spaces and structures that are glibly labeled “iconic”, even while no effort is spared to desecrate and vandalise them.

I am constantly connected to my companions in adversity. We exchange news and views night and day. We argue, we share and we lament. But sitting in my house that is not mine, my city that is not mine, my body that is not mine, I know what’s happening: The world is once again coming to an end.

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Ananya Vajpeyi is a writer and a scholar at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, New Delhi