What we do with our dead, how we regard them, is dependent on the specific conditions into which we are born—belief, religion, language, place, sect, caste, gender and, in recent times, science. In India, those classified as “untouchables” or “Dalits” have been forced to handle the dead for centuries. The manner in which they are compelled to do this in modern, state-run hospitals, have gone unnoticed and undocumented. My project proposes to shine a light on an unknown, shrouded world and to look at how this caste evolves during the time which takes shape in new practices. Autopsy was introduced in India a few hundred years ago by British medical practitioners.

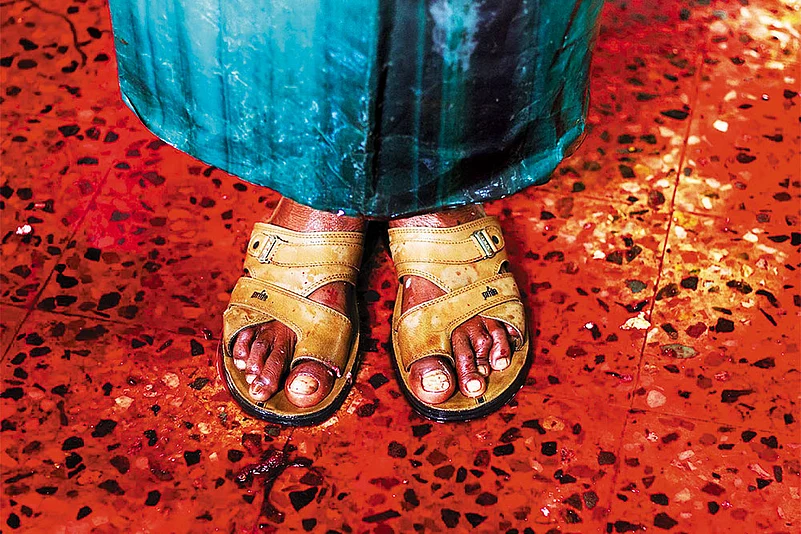

A woman’s feet on the bloodied floor of a morgue

We live in a time when unnatural deaths are subjected to investigation. Before a surgeon handles the body, a team of trained staff prepares it. There are elaborate procedures relating to how the body should be handled and what the qualifications a technician should have. After the autopsy, highly skilled work is performed; the corpse is wrapped; the ventilators are removed; no visible incision is left to be seen; the viscera are carefully handled, and the body is reconstituted by sewing it back together. In all this, the coroner is assisted by a team of lab technicians.

A body with its token

Body being prepped before it is handed over to relatives

In India, the reality of this process is shockingly different from our perception. In almost all hospitals in India, a range of tasks, sometimes even the opening of the torso with the Y-incision, is done by semi-literate staff, all of them Dalits. Official identity cards designate the men as “sanitary workers.” Much like other stigmatised work in a society organised by caste, such as handling all manner of waste (including human excreta), the cleaning of sewers or skinning of animal carcasses, this modern work too has become hereditary. The ill-equipped workers, with outmoded refrigerators and crude implements, perform tough tasks under dismal conditions. They suffer from several occupational ailments and work-related infections from handling the decomposed, verminous bodies. Tasked with endowing dignity on the dead, they face a social death. The untrained, underpaid Dalits cannot tell their friends and neighbours what they do for a living.

Freezer rooms of a new mortuary

Worn out staff chairs

A mortuary archive and record room

I began this work in 2016 and continued until 2018. Since the Covid lockdowns of 2020, travelling and access to mortuaries became impossible.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Death, Up Close")

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Arun Vijai Mathavan is a photographer based in Bangalore