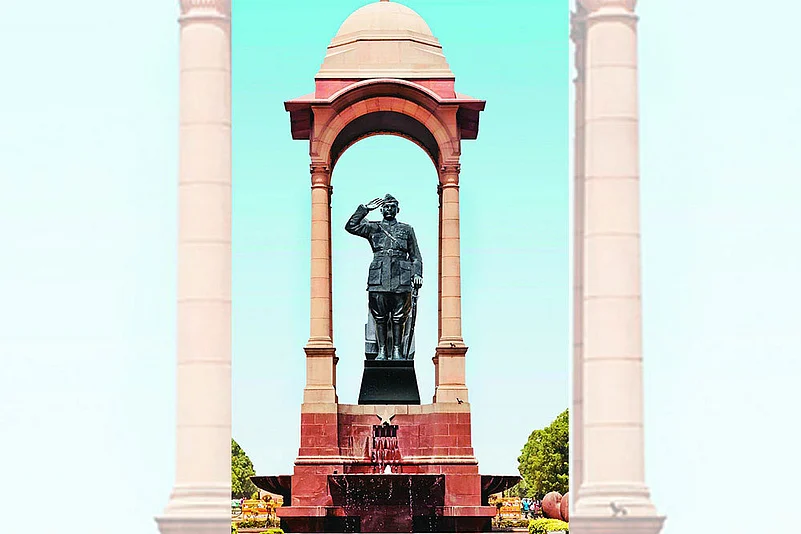

The installation of Subhas Chandra Bose’s statue at India Gate is not the addition of one more statue, it also leads to the larger question on Indian historiography. On March 10, 1965, sixteen members of the Lok Sabha—including H.V. Kamath, L.N. Singhvi and N.G. Ranga—had asked a question about the central government’s stand on the proposed installation of Mahatma Gandhi and Bose’s statues in New Delhi. The then home minister Gulzari Lal Nanda replied about Gandhi’s statue but remained silent on Bose’s, to which Ranga quipped, “What about the other name? Is it so unspeakable that the honourable minister is not prepared to mouth it? What is the big idea?”

The installation of Bose’s statue by PM Narendra Modi should be seen in this light. It can be termed as the emergence of a counter-hegemonic idea which has popular support. A counter-hegemonic idea becomes reactionary when you try to demolish an established tradition, but it becomes constructive when you make things more inclusive. Modi has not taken recourse to a negative narrative, instead he’s trying to make it more inclusive by enlarging the social space and ideological diversities of the Indian freedom struggle. Every nation has to celebrate its icons who contribute to national life. But in a fractured polity and intellectual life, contemporary politics based on narrow divisions cast a shadow on historical personalities too.

There is an interesting instance. When Otto Von Bismarck, known for consolidation of the German nation, died in July 1898, no state funeral was held for him. It was written on his tomb that he was a “loyal servant to Kaiser Wilhelm I”. He founded the German nation and served the people, but local differences ensured that he didn’t get his due at his death. This is a classic example of fractured polity. It blinkers our vision. We don’t think beyond narrow ideological and political bitterness. This phenomenon has partially haunted Indian historiography and the heirs of the Indian State after Independence. Jawaharlal Nehru and his successors failed to give an answer on Bose’s statue in New Delhi which Ranga had summarised in a counter-question, “What is the big idea?”

When Modi came to power in 2014, he displayed a large-heartedness that Nehru as the PM could not. Shyamji Krishna Varma was a great revolutionary leader who even inspired Ghadar Party leader Lala Hardayal. He went to London and, after being hunted by the British police, escaped to Geneva. He also published a magazine, Indian Sociologist, and founded India House in London that became the centre of revolutionary activities. He wrote in his will that his ashes be brought to India after it becomes independent. He died in 1930 in Geneva but successive Indian governments failed to honour his will. His name remained in the dusty pages of Indian history books, dismissed in a footnote. After Modi became the Gujarat chief minister in 2001, he brought Varma’s ashes from Geneva in 2003, and also constructed a memorial in Bhuj, named Kranti Teertha, and installed his statue.

Heroes all Statues of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev at the Shaheed Park in Delhi. Photograph: Tribhuvan Tiwari

This shows that the RSS and Modi’s worldview of nationalism does not rest on ideological and local (in terms of time and context) differences. Anyone who contributes to the nation must be honoured and exalted. Local differences should not become universal differences. It is the moral responsibility of any vibrant society and the State to go beyond such conflicts. Sardar Patel, who has been described as India’s Bismarck, faced discernible discrimination by successive Congress regimes. Modi, after becoming the PM, exalted his contributions in nation-building and his statue, the tallest in the world, was erected in Gujarat. The Congress made sarcastic remarks on the BJP and the PM, that since RSS lacked their own icons, they hijacked icons who belonged to the Congress. This negative narrative of the Congress is an attempt to define the past by the present. The contributions of Patel, Bose or Varma belong to the entire nation and not only to the past, but also to future generations.

ALSO READ: Statues And The Construction Of Memory

The installation of a statue or exaltation of a personality reflects the nature of historiography a nation has. Indian history has been written in the shadow of Nehruvian and Marxist domination. Ideological and political differences guided the historians who were largely patronised by the State. What happened in the pages of history was reflected through statues. The debate on statues has another dimension in a society which was once a colony. The process of decolonisation depends on the method of the liberation movement. When a country achieves independence by challenging the corrupt, coercive and anarchist imperialist regime through violent struggle, then decolonisation becomes all inclusive—politics to culture. As Franz Fanon aptly said, “Colonialism is not a thinking machine…it is violence in its natural state, and it will only yield when confronted with greater violence.” Colonial traces need to be removed not only from politics but also from cultural and social spheres.

Indian philosopher K.C. Bhattacharya said in 1931 that swaraj as an idea is essential for a post-colonial society. But when the struggle is accompanied by a consistent dialogue with colonial forces, it creates a socialisation between an influential section of national leaders and colonial forces. The colonial forces in turn give legitimacy to such modes of movement. This socialisation and mutual dependence become detrimental to the decolonisation of ideas. It was reflected to an extent in the Indian political discourse after independence. In 1969, Dattopant Thengadi raised a question in the Rajya Sabha whether some government buildings still carried the symbols and insignia of the British. A similar question was raised in 1965 by another parliamentarian on why the statues of Queen Victoria, King Edward and King George continued to be on Indian land. On both occasions, the government’s response was based on escapism. It said the statues would be removed in due course. The government also responded that the four pillars between North and South Block were the insignia of the Commonwealth. The presence of British kings and queens’ statues in New Delhi was interpreted as India’s non-vindictive attitude by historians and ideologues of the Congress.

ALSO READ: Deciphering Mayawati’s Monumental Pride

But these British kings and queens were responsible for brutal violence on the Indian people and such martyrdom included 12-year-old Baji Rout, Tileswari Barua, also 12, 15-year-old Shirish Kumar Mehta, Ramanand Singh and six other boys who wanted to hoist the national flag at the Patna secretariat on August 11, 1942. Any sympathy with such imperial rulers is an insult to the martyrdom of the brave freedom fighters of India. It again proves that India’s decision to be part of the Commonwealth was partial subjugation.

When the Modi government renovated the Jallianwala Bagh memorial, a section of pseudo-secular people and Congress tried to misinterpret it. The fact is, while a hospital in England where General Dyer died still preserves the memory of his barbaric act, the Jallianwala Bagh memorial remained neglected and ignored under the control of the Congress. PM Modi took a holistic approach towards the makers of India. That’s why Dr Ambedkar’s legacy is also given equal importance. When the question of dismantling the statue of Cecil Rhodes in Oxford emerged, England’s prime minister said that “history cannot be edited”. But such people forget that statues of socially and politically reactionary people are like seeds for the future which can germinate reactionary ideas. Therefore, de-iconisation is as necessary as iconisation. The removal of the statues of imperialist forces in India and PM Modi’s efforts to celebrate leaders from Rani Jhansi to Rani Gaidinliu make a marked difference between the old regime and the New India and is a pointed answer to Ranga’s question to the Congress, “What is the big idea?”.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Decolonising Our Icons")

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

Rakesh Sinha is a BJP MP in Rajya Sabha