Covid-19 is a two-fold, antithetical problem of human health and economy, wherein when one gets a respite, the other begins to asphyxiate. The gradual “unlock” process including the phased removal of Covid-19 related restrictions has ensured that the economy gets a breather. However, the very same removal of restrictions has increased the common man’s vulnerability to the virus both in urban as well as rural India.

The policy of segmenting the country into different zones and devising unique strategies to deal with the pandemic in each zone has resulted in better management and containment of the virus. This further proves that practices and measures suggested by the centre need to be adhered to, by all state governments with necessary improvisations to address local concerns. This will ensure that states function with a spirit of self-sufficiency and self-sustenance, especially in the healthcare domain.

However, if there’s anything that this pandemic has proven, it is the fact that there’s an urgent need to develop primary health care facilities especially in rural India. Healthcare facilities in rural India are abysmal. Lack of healthcare workers, low level of awareness among the masses and rising Covid-19 positive cases have put an immense strain on the medical infrastructure in the country’s villages and towns. The very foundation of the healthcare sector has been put to test ever since the pandemic started.

Unlike urban areas where there are 4,375 government hospitals with 4,48,711 beds, rural areas have more hospitals (21,403) but with only 2,65,275 beds. With 66.1% of the country’s population living in the countryside, we are at the brink of a great calamity, which will prove catastrophic if immediate action is not taken.

Most of the rural population is dependent on government funded public facilities and Community Health Centres (CHCs). Even though rural areas have approximately 5335 functioning CHCs, there is a massive need for more such centres, especially in states like Bihar. In contrast, Kerala’s CHCs seem to be handling the Covid-19 pressure very well. This might be because Kerala spends 6.5% of its GDP on health care. In comparison, the centre currently only spends 1.7% of the country’s GDP on health care. Therefore, the difference between the regions which have effective and organised healthcare units in smaller pockets and those which do not is huge.

Many CHCs have been converted into fever clinics to minimise the risk of cross infections. CHCs have proven to be effective in controlling and regulating the number of new infections. However, instances of many states relying more on government hospitals without involving CHCs, points to the underdeveloped healthcare infrastructure in the state. Simultaneously, state governments have converted bigger hospitals, handling regular, non-Covid-19 cases into Covid-19 care centers. This has resulted in these hospitals becoming the first point of contact with the virus.

At such a time, our ministers and MPs should have worked on upgrading essential healthcare facilities in their respective constituencies. Sadly, with the suspension of MPLAD funds, the dream of achieving this objective has become even more impossible. The suspension of the MPLAD funds has disrupted many development activities being carried out by individual MPs in their constituencies. In such a situation, one cannot stress enough on the effectiveness of decentralised governance and progress achieved in working in small groups rather than working in a centralised manner. Snatching away the MPLAD Funds from the hands of MPs has directly resulted in slow or no development of CHCs in rural areas for the past six months.

This pandemic has to be fought at the grass roots level. Local committees need to be set up under the Rogi Kalyan Samiti Scheme to upgrade public health infrastructure in rural areas. This will provide twin benefits. First, the residents of these areas having mild Covid-19 symptoms, can be sent to their respective CHCs after treatment. Secondly, it will reduce the movement of uninfected patients to state hospitals or far away centres.

Infrastructure development coupled with hiring more healthcare workers, will help the country’s rural health care centres to fight this pandemic in a decentralised and more effective way.

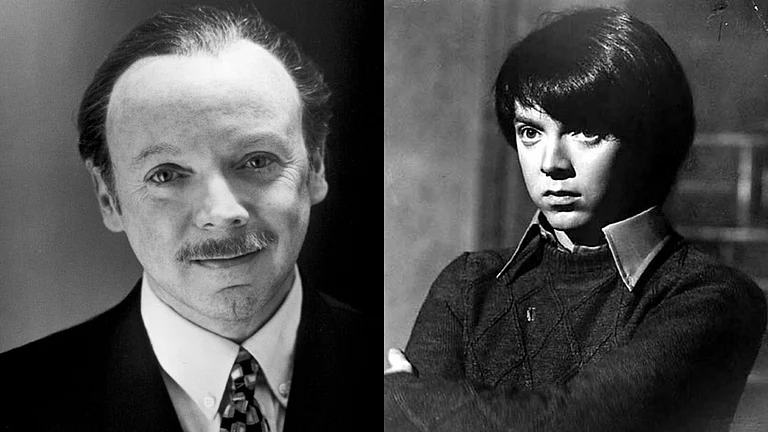

(Views expressed are personal. Kunal Saini is a student at International Law Department, The Graduate Institute Geneva, Switzerland. Pragati Dhawan is a student at Campus Law Centre, Faculty of Law, University of Delhi.)