In their symbolism and social genesis, the dacoits of old and the gangsters of today are different species. Yet, the most clinching line—applicable to both—was spoken by the most famous dacoit of film in a classic call-response format. ‘How much has the law put on my head?’ A triumphal: ‘A full fifty thousand!’ And then, to the eerie accompaniment of curry western banshee tunes, the dacoit slowly intones the heart of the matter: the true capital of an outlaw lies in the legends that prevail about him...or her. Cinematic references aren’t out of place: they form part of the web of awe, the tissues of legend that bind two very real worlds. That of the outlaw, and those who live under the shadow of their dread. Real-world gangsters can be a far cry from pastiche shaitans of screen—their world quite humdrum and dreary—but they share this one trait. The legends make them who they are: a carrier of the fear-currency, which work by opening a window into their arcana. Seemingly trivial yet fascinating nuggets of detail that betray their worldview, their instincts, their aspirations, their approach to life.

There used to be a gangster in Lucknow, in the ’90s, who went by a name that could belong to an upper division clerk: Shri Prakash Shukla. He always carried a kit bag with him, they say, in which he kept his office equipment: an AK-47. Upon spotting the person to be bumped off, he’d merely stick the gun’s nozzle out of the bag and spray bullets into the person’s body. During the late ’70s-early ’80s, a rebel/dacoit called Chhabiram prowled the Chambal ravines on the edges of the districts of Etawah, Mainpuri and Firozabad. The story goes that once he kidnapped a police officer, and held him hostage till his wife reached and surrendered all her jewellery. Now the twist: while leaving, she addressed the dacoit as “bhaiyya” (brother)…his heart melted and he returned all the booty. The closest to filmic luridity is, of course, the famous legend about mafia don Raja Bhaiya of Pratapgarh—the way he fed his enemies to his pet crocodiles that live in the pond at his estate.

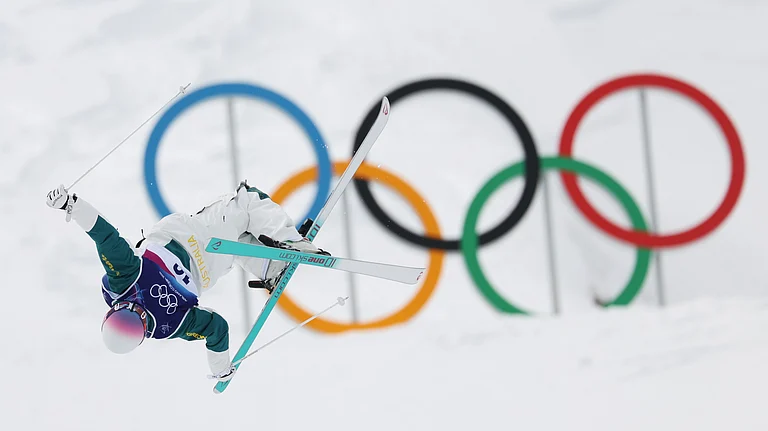

Catch before kill Vikas Dubey being led away after his arrest in Ujjain

Bombay may hold the patent on an underworld with a much higher GDP and media cachet, but there’s something about the dusty UP-MP continuum that breeds a special kind of desi badness—and by now the lines between the law and its opposite aren’t very clear. It’s all over the news again—enter (and exit) Vikas Dubey, a gangster from Kanpur. After eight of the cops who had apparently gone to arrest him were gunned down in Bikru village on July 3, one of the gangster’s henchmen arrested later offered a nugget. The tip-off about the raid, he alleged, had come from the local police station itself. The bullets ricocheted over the next eight days, and Dubey and at least four of his gang lay dead. Dubey’s death, barely out of media cameras, offered one more instantiation of that bound script reserved for encounters. Only the minor details change: an arrest in Ujjain, a jeep overturning en route to Kanpur, Dubey snatching a cop’s pistol and firing in an escape attempt, bullets in self-defence, a corpse. Most feel it’s almost intended to be taken as a cock-and-bull story.

Raja Bhaiyya belonged to a new crop of Uttar Pradesh’s criminal-politicians

What we all saw, as if through a rifle’s sight, is a slice of Uttar Pradesh’s grubby crime life—the culture that gave birth to a don like Dubey. The style and content of crime varied greatly in UP, in terms of place and decade. The ravine dacoits who used to inhabit a strip along the Chambal river valley—which overlaps parts of Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and UP—have long given Bollywood its version of the Wild West. The real ones, locally called ‘baaghi’, had a touch of what that word means: conscientious rebel. Many of the dacoits, including the infamous Mohar Singh who passed away two months ago, surrendered ages ago—from 1960 onwards at the behest of Vinoba Bhave, some in 1972 through the efforts of of Jayaprakash Narayan, some in 1976 under the chief ministership of N.D. Tiwari in UP, and some in 1982 and 1983 to Arjun Singh, then CM of MP.

UP: In Bullet Points

These four decades or so in between those days of dacoity—a remnant of a pre-modern, feudal order—and present-day gangsterism offer us a fascinating alternate social history of UP. Many things change: the methods, the guns, the social profile of dramatis personae, and their slow entrenchment in power. The conscientious rebel morphs slowly into an amoral killing machine on hire. But it’s the interplay of power with the realm of crime that cuts the deepest in terms of insight. And it’s not just a question of saying, loosely, ‘India is cursed with a criminal-politician nexus’. Politics changed, power entrenched for centuries was shaken. As Indian democracy evolved, a static social order with its monopoly on power began to be challenged. On the fringes of society, the baaghis were beginning to reflect this transition.

A few elements would seem to have endured since those days—the question of policing, for one—but in reality even that is not impervious to an internal evolution. The anti-dacoit operations during V.P. Singh’s tenure as CM led to the killing of at least 1,500 persons between 1981 and 1983. “Many small-time offenders, even innocents, were killed in the madness of it. V.P. Singh’s brother, an Allahabad High Court judge, was killed in March 1982 and the fuming CM told the police to eradicate dacoity. But there was no monitoring happening whether actual dacoits were being killed,” says Anand Lal Banerjee, former chief of UP police, who was then a young officer. Very often, it is said, police footsoldiers would risk their lives to kill a dacoit and the senior officer would later come and claim credit. Or they would tie the dacoit to a tree for the boss to come and do the honours. The idea of vendetta was already there. Take the reported words of a UP cop, uttered when bandit queen Phoolan Devi was going to surrender in Madhya Pradesh: “Phoolan hamara shikaar hai (Phoolan is our prey).”

Phoolan Devi surrenders before then MP CM Arjun Singh in 1983

A raging police force being in a rush to score high in the numbers game—or out on a thinly disguised vendetta spree—will be a familiar thought to today’s reader. A trigger-happy approach has marked policing under the Yogi Adityanath government too, with over a hundred encounter deaths in the past three years. The same charges of petty offenders and innocents being killed in cold blood are being levelled today. And Dubey is seen as classic vendetta, just off the files. But the moral greyness that pervades the whole sphere of the criminal justice system today was just taking shape. Just like dacoits could have a heart of gold, cops too could often operate within the old frame of duty and social conscience. How did everything change? Well, black and white slowly came together to give us grey.

Mukhtar Ansari, the politician from Chandauli

“Organised crime took shape and emerged around mid-’80s and graduated around mid-’90s,” says Vikram Singh, former director general of UP police. “The key areas were contract killing, booth-capturing, bootlegging, government contracts, protection money, kidnapping, human trafficking, fake currency. Small criminals with a few crores flowing would go on to become a sarpanch or gram pradhan or block pramukh. Beyond ten crores, he would run for MLA. You have any number of criminal elements graduating into politics and doing well for themselves. They were enabled by an eager group of corrupt politicians, an aloof judicial system and a complicit police. It’s a huge banyan tree of complicity.”

The kind of crime changes—well, expands. The crimes prevalent in western UP around the ’70s-’80s were mostly kidnappings and extortions. If a sugarcane farmer in and around Muzaffarnagar had a good harvest season, his son was certain to be kidnapped. Wealthy businessmen in the industrialised districts of Ghaziabad and Meerut too mostly lived in fear of kidnappings. Kidnappings are in no danger of going extinct, but other elements were being added to crime, mirroring social change. The land reforms of past decades, to the extent they worked, gradually made the role of the lathait (stick-wielding musclemen) in tax collection obsolete. They were eventually absorbed for the purpose of securing government contracts, and as local influencers of votes. Slowly, they realised it was senseless to stay out of the system. The outlaw began to come in.

On the state’s eastern extreme, Gorakhpur was an important district: it was the headquarters of North-Eastern Railway. The meaty contracts for railway scrap soon became a point of dispute between two mafia dons, Hari Shankar Tiwari and Virendra Pratap Shahi, allegedly supported by Congress leaders from opposing factions, Kamlapati Tripathi and Vir Bahadur Singh, respectively. Gang wars between the two often erupted in the streets of Gorakhpur. The new don was here: Tiwari was an MLA for all of 23 years. He has the BJP, SP and BSP all on his resume, and has been a minister too in regimes helmed by all three parties. That’s the case with most mafia dons; they have been associated with almost every party that has been in power. Shahi didn’t have as long a run as Tiwari—he was gunned down in Lucknow by Shri Prakash Shukla in 1997; he had won just two assembly elections till then. Shukla was all of 24 at that time. A bit of a madcap, he had a swanky lifestyle and harboured the ambition of becoming India’s top gangster. In that sense, he was similar to Dubey, who was greatly impressed by Sunny Deol’s character in the movie Arjun Pandit and urged his associates to call him Panditji.

Shukla had taken the contract to kill then CM Kalyan Singh, a BJP leader had alleged. The allegation seemed to stem from personal rivalry but was enough to prompt a full-scale effort to hunt down the gangster. Shukla had also killed a Bihar minister—a contract—and Tiwari was believed to be one of his next targets, after eliminating whom, he wanted to lay claim to his Brahmin-dominated assembly seat in Gorakhpur. The dream was short-lived: Shukla was gunned down in 1998 in Ghaziabad by the Special Task Force (STF) of UP Police, after a five-month chase, criss-crossing roughly one lakh kilometres, and costing the exchequer about one crore rupees.

The most damning revelations came about in the STF report on Shukla’s connections: it was practically an encyclopaedic entry on the criminal-politician nexus in the state, or better put, the coalesced mass of criminals and politicians that governed UP. The report said Shukla had colluded with at least eight BJP ministers—who often gave him sanctuary in their official residences—and several politicians from other parties, bureaucrats and police officers, all of whom had been helping him evade arrest. A car he used in kidnapping was traced to a service station: the booking for it was done by Amarmani Tripathi, another don and four-time MLA who has been associated with all four parties and now serving time in jail for the murder of poetess Madhumita Shukla.

On the southeastern corner of UP, Mughalsarai (Chandauli) was another focal point of crime and commerce: a major railway hub, coal coming from the mines of Bihar and Jharkhand would get reloaded and redistributed here. Pilfering and informal coal mandis, like the one in neighbouring Chandasi, were the order of the day. Mukhtar Ansari and Krishnanand Rai were rival politicians who fought over domination in the region. The latter, along with six other men, were killed by Ansari’s henchmen led by Munna Bajrangi in 2005. A total of 67 bullets were recovered from seven bodies, after one of the bloodiest gangwars in the state. Bajrangi himself was killed in Baghpat jail in July 2018. Another gangster shot him ten times in the head.

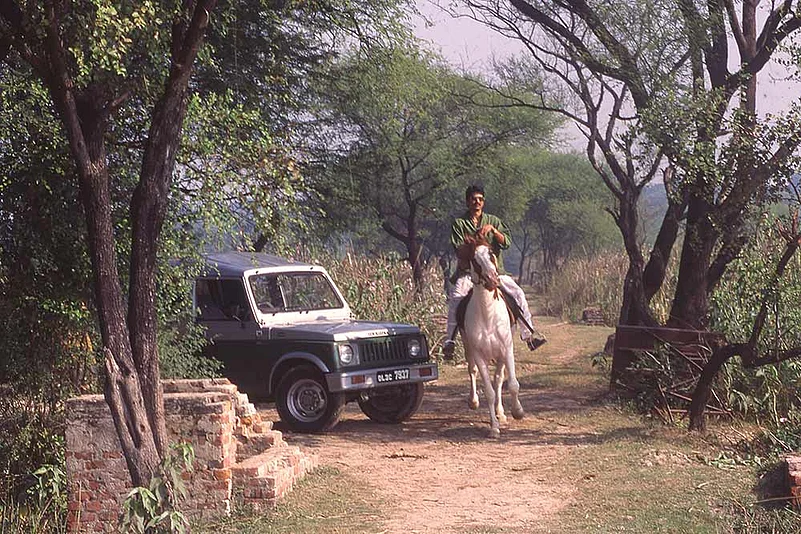

Old-world baaghis like Malkhan Singh had principles, led simple lives

Other names emerged in this phase—Raja Bhaiya (Raghuraj Pratap Singh, a Doon School dropout), Atiq Ahmad and D.P. Yadav out west. Dozens of criminal cases, murders, gang wars, sinister reputations, yet fairly successful careers as politicians: there’s little complexity to these men. The gold standard for criminal-politicians, they never had much use for the perfumes of Arabia: crime is their USP. Atiq and DP are in jail at present. These people too changed parties but have been majorly associated with the SP, which ruled UP for ten out of the past 20 years, and is seen by the urban classes as an enabler of this new, unabashed marriage of law-making and law-breaking. But of course, they have no exclusive claim on this: their presence is a mere marker of a larger sociopolitical change.

But how did things arrive at this in a constitutional democracy? When and how did the line between the law and crime begin to blur? Says Milan Vaishnav, director and senior fellow at South Asia Program, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, and author of When Crime Pays: Money and Muscle in Indian Politics, “The turning point in most states, including UP, was the Emergency. Before that, criminals were operating largely at the periphery of politics with politicians enjoying centrestage. They would treat criminals as hired guns to do their dirty work around elections. After the Emergency, we see a ‘vertical integration’ of criminals and politicians. The numbers really take off in the late ’80s-early ’90s, when the party system gets massively disrupted due to Mandal, Masjid and Market.” The established party monopolies, that is, controlled by the old social elite.

ALSO READ: The Smoking Gun

Anil Kumar Verma, director, Centre for the Study of Society and Politics, Kanpur, writing for Outlook recently, pinpoints the late ’70s-’80s as a time of churn in UP politics. “That was the time when Dalit and backward assertion…came to dominate the state. Its political avatars [in the form of BSP and SP] gave patronage to such criminal elements because they had to build their parties from scratch. At that juncture, criminality was amalgamated with caste identity so that marginalised caste groups would see their criminal-politicians as a symbol of ‘caste pride’. Such criminal-politicians claimed the backing of peoples’ mandate,” he wrote.

Many people do not see the State as an impartial provider of basic goods and services, elaborates Vaishnav. So a politician can use his criminality as a sign of his capacity to “get things done” for his constituency by any means necessary. But UP mostly gets a disproportionate amount of notoriety, even though the politician-criminal nexus is found in every state. “UP often gets singled out as an outlier; it is not,” says Vaishnav, “Bihar, Maharashtra, Jharkhand—to pick a few examples—have very high rates of criminality. Not to mention that Gujarat or Kerala are hardly paragons of political virtue. I think the north Indian preoccupation is partly a result of the cinema culture where the idea of a ‘dabang’ don running amok in the badlands is prevalent.” The percentage of legislators with criminal records attest to this—35 per cent in UP, 23 per cent in Rajasthan, 23 per cent again in Punjab, 40 per cent in MP, 35 per cent in Karnataka and 60 per cent in Maharashtra.

Daakus On The Move

Before the easy formulations of criminal politics—white-collar crimes of global proportions never seem to make it—we can trace that movement through a clutch of transitional figures in UP. A gradual deepening social meaning. One of the most dreaded dacoits of that cusp phase, Raghuvir Singh Yadav, better known as Chhabiram, was killed in March 1982 along with his 11 other gang members after a seven-and-half-hour-long chase and gunbattle in which a total of 9,000 rounds were fired. Chhabiram had killed 24 policemen and carried out over a hundred dacoities, the victims of which were wealthy sahukars and zamindars. While many dacoits avoided confrontation with cops, or at least dithered over killing cops, Chhabiram would surround and kill them. Whenever raided, his gang would split into two; while one team would engage the cops, the other, led by Chhabiram, would encircle them and kill them from behind.

The police had smartened to the tactics by the time the final ops were launched—with political will, and pressure, behind them. Chhabiram’s contemporaries Pothi, Mahavira, Anar Singh and others too were killed around then. After Chhabiram died in that epic battle, Sukarm Pal, deputy SP of Mainpuri city, told a pressman, “In a way, it was sad to see a brave man die.” A senior journalist from Lucknow, Pradeep Kapoor, reached Mainpuri the day after the shootout. “His body was kept at the kotwali. Many people from the villages had massed outside. In a casual manner, I said people will now heave a sigh of relief. But they immediately mobbed me. ‘You have come from Lucknow wearing a jeans and shirt. What do you know? Netaji (Chhabiram) is gone! Who will save us from police harassment now?’ one of them said,” recollects Kapoor.

Gangster Atiq Ahmad, now in jail, was Samajwadi Party MP from Phulpur, UP

Another dacoit, extremely elusive, who reigned for almost a quarter of a century in the Chitrakoot-Banda region, from the 1980s till his death in a police encounter in July 2007, was Shiv Kumar Patel, better known as Dadua. A hero of the Dalits and backward castes—he was a Kurmi himself—he committed some 150 murders and 200 dacoities. A police officer confessed the police had been unable to hunt him down because of the support he enjoyed from Dalit and backward castes. But Dadua was ruthless when it came to police informers, often torturing them for long before killing them. He often used hired hands, and in the later years, gave up dacoity and kidnappings and drew a fixed share from government contracts in the region.

In the initial years, he reportedly had the patronage of CPI leader Ram Sajeevan, who later joined BSP. Once the police had almost chased him down in 2004, right before the Lok Sabha elections, and were going for the kill when news reached the high-ups in the state government, then of SP, and he was saved. Days later, a few hundred village headmen he wielded influence over pledged support to SP. The day Dadua was finally gunned down by the STF in 2007, Ambika Patel (Thokia) ambushed the triumphant returning posse and killed six STF men. Hours later, Thokia met his end too. Around those years, bandits Nirbhaya Gujjar and Ghanshyam Kewat were also gunned down—their surnames a marker of their backward origins. The latter held thousands of cops at bay for over 52 hours in a gunbattle, all alone, armed with only a .315 bore rifle. Besides the royal embarrassment, the police force lost four men and six others suffered grave injuries.

The caste matrix showed a feudal order in the throes of change—with all its old-world values.

Malkhan Singh, now in his late ’70s, surrendered in 1982. Describing him and his contemporaries, Lucknow-based senior journalist Dilip Awasthi says they were simple people, absent any craft or cunning. “I happened to see a diary of Malkhan where he had noted the expenses of his gang. The entries were of wheat flour, soap, money given to a guest, etc. It looked like a diary from a poor household,” he recalls. Malkhan became a baaghi—as they preferred to call themselves too, taking objection to the nomenclature ‘dacoit’—after he was harassed and implicated in false cases for objecting to usurping of temple land in his village. “The question of survival always kept them on their toes. They were true to their words and also had some principles, never troubling women or poor,” says Awasthi. Whether this was born out of necessity or benevolence is tough to say.

Many of them had a Robin Hood image, often helping the poor, dispensing justice in disputes, and almost invariably giving money for weddings in poor families. Adjusting the loot amount against the philanthropy, they weren’t left with much. Jalaun SP Uma Shankar Vajpayee once told an interesting story to a news magazine. Visiting a village in Chambal district, he was surprised by the warm welcome he got there. But as soon as the villagers found out he and his team were policemen, and not dacoits—the latter wore khaki too—the geniality vanished! The old dacoit life was a tough one, always on the move, living in the open, exposed to insects and wild animals, and many chose it only after facing injustice at the hands of police, or village head, or a more powerful person in the village. The story of Paan Singh Tomar—subject of an eponymous film, played by the sublime Irrfan Khan—is a living chronicle of that reality. Paan Singh’s nephew Balwant surrendered with Malkhan. Those days seem almost prelapsarian in comparison to the age of Vikas Dubey. But he only comes at the fag-end of a graph of criminality that moved through backward caste assertion to Brahmin gangsterism— all the Shuklas and Tiwaris and Tripathis—and that was an interesting bridge that UP had already crossed in the tumultuous ’90s, the decade of change.