In mankind’s war against a touch-sensitive nanoscopic virus, the soldiers wear scrubs and the war machines dispense hand sanitisers, sterilise hospitals and public spaces, report people breaking stay-at-home orders, or tell if you have come in contact with an infected person. Savvy. But do we have machines and technology to tame an advancing army of mutating, multiplying rogues—like Raktabija the asura who had a clone from each drop of his blood that fell on the ground? Not yet. We are not used to such wars—since that Stone Age giant learnt to strap a sharp flint onto his spear, we trained our brain to build tools to massacre our own species. We never created a missile to slay itty bitty bugs that have killed more humans than all the wars combined. Maybe we will find a revolutionary cure eventually. Until then, we are at the mercy of our evolutionary immune system and the sneaky police drones hovering above our rooftops or by our balconies, checking if we are socially distanced adequately. Don’t be startled if you hear a whirr of propellers and a siren blast. Woop woop, wooooooohhhh! They got you (out and about without a mask).

Yet, as history points out, humans adapt and adopt new tools as the war progresses. Who thought an unmanned flying object—Garuda, a drone—would disinfect the alleys of ancient Banaras, where purification of the soul presides over life, death and paan spits. Garuda’s first assignment was spraying disinfectants on a coronavirus hotspot in Madanpura, a heavily populated locality. It removed any need to deploy a civic worker for the job and expose him to infection. Similar janitor drones—which we saw with mouths agape on widely shared WhatsApp videos from China in the early days of the pandemic—are on duty in most major cities and towns in India. The eagle Guruda, god Vishnu’s steed, is finding flight deep south too, minus the ‘a’. Kochi startup AI Aerial Dynamics has created the unmanned ‘Garud’ that can monitor body temperature, supply essentials and mist-spray disinfectants.

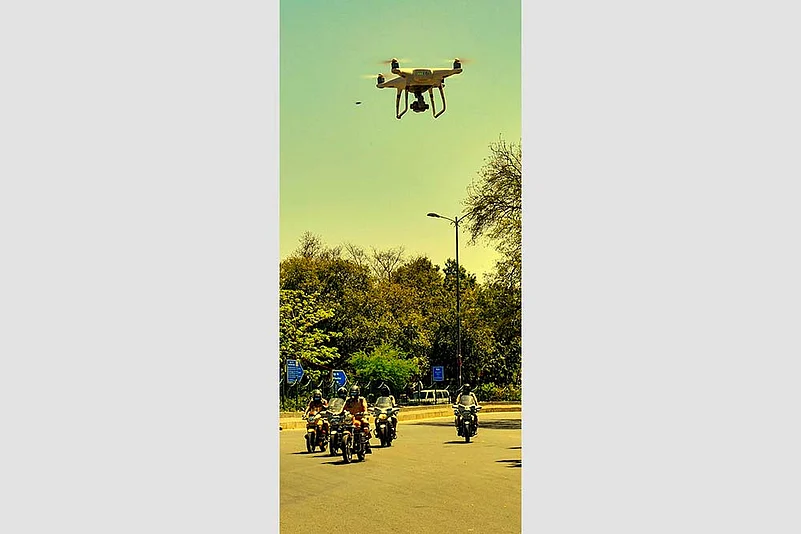

Personal protection—a cop stands guard in Delhi; a woman goes through a sanitising kiosk before entering office; a UV-ray machine to sterilise public spaces

In Mumbai’s Dharavi, another COVID-19 red zone, firefighters use the advanced aerial mist-blowing machine Protector 600 to sanitise the area. In Telangana, engineering and technology solutions company Cyient has given the cops drones kitted out with surveillance cameras to monitor congested areas, thermal imaging payloads and sky speakers for public announcements. “The geothermal camera surveys an area and provides accurate details about the number of people inside a building or on a road. If 200 people are in a building, the camera reads the body temperature of each one of them from a distance and alerts authorities in case of deviations,” says Ankit Kumar, founder of Alternate Global, who is working with several states on drone surveillance.

Drones are old hag—not quite the novelty that it was when the 2009 movie 3 Idiots featured a quadcopter designed by two IIT Bombay students. These have been around for quite some time. The BSF uses one called Netra. Our pre-wedding videos aren’t complete without ‘sky’ shots from unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV). But flight restrictions keep private drones away from cityscapes for issues ranging from ‘sensitive installations’ to people’s privacy. The Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) allows only drones made by Indian companies to fly and its approval is mandatory before each flight. There are about 15 companies founded by Indians that manufacture drones and the country has 19,000 owners of UAVs. The number could be much higher, but many owners don’t register their machines with the DGCA, which provides each drone a unique identification number. The civil aviation ministry has launched a GARUD (Government Authorisation for Relief Using Drones) portal to fast-track conditional exemptions for drones operated by government entities for pandemic-related work.

As governments around the world consider how to monitor new coronavirus outbreaks while reopening their societies, many are starting to bet on smartphone apps to help stanch the pandemic. But their decisions on which technologies to use—and how far those allow authorities to peer into private lives—are highlighting some uncomfortable trade-offs between protecting privacy and public health. Smartphone apps could speed up the process of tracking by collecting data about your movements and alerting you if you’ve spent time near a confirmed coronavirus carrier. But people are less likely to download a voluntary app if it is intrusive—data collected by governments can also be abused by governments—or their private-sector partners.

India has voluntary government-designed apps that make information directly available to public health authorities. Like the Centre’s Aarogya Setu, a contact tracing app that can alert people when they have crossed paths with an infected person. The app has recorded more than a million downloads since its launch. But such containment efforts raise privacy and civil liberties concerns. Congress leader Rahul Gandhi has already alleged that Aarogya Setu can be used to snoop on citizens, a charge the government denied. President Trump fears that a joint initiative by Google and Apple to develop a smartphone “contact tracing” tool would infringe people’s freedom and privacy. But developers suggest these apps rely on encrypted “peer to peer” signals sent from phone to phone; these aren’t stored in government databases and are designed to conceal individual identities.

Most coronavirus-tracking apps rely on Bluetooth, a decades-old short-range wireless technology, to locate other phones nearby that are running the same app. The Bluetooth apps keep a temporary record of the signals they encounter. If one person using the app is later confirmed to have COVID-19, public health authorities can use that stored data to identify and notify other people who may have been exposed. Delhi has the ‘Assess Koro Na’ app for door-to-door survey in containment zones. In Punjab, it’s the COVA app that alerts people when they come in close proximity of an infected person. The IITs and the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bangalore, have developed apps like GoCoronaGo and Sampark-o-Meter for contact tracing. These apps record a digital trail of the strangers an individual encountered. But they are of no use if one comes in contact with an asymptomatic person who hasn’t been tested. The only way to find infected people showing no signs of the disease is to ramp up testing. A tough ask for a country of 1.3 billion people, and an entirely different story.

Such apps are just one part of the grid. The smartphone—Amitabh Bachchan called it “the invention of the times”, although “the wheel has been dubbed as the greatest invention of all times”—has been a saviour for several sectors. Online classes for students, medical consultancy…the list carries on. But the biggest limitation: many people, particularly in vulnerable populations, don’t carry smartphones. Only about 45 per cent cellphones in the country are smart. Connectivity is poor and only 40 per cent of cellphone users have access to the internet. Experts suggest information from apps will work best if amalgamated with data from an extensive network of face-recognition cameras (FRC) at public places to support the surveillance system. “The FRC providers are working on converging thermal camera and FRC software to get facial recognition-based flu detection solution,” says Bikas Jha, the country head of Real Networks, a US-based company. Indian firm Vehant Technologies has developed FebriEye, a thermal screening system with additional analytics like face mask and social distance monitoring. It generates an alarm in case of any deviations. The camera is likely to be useful at entrances to events, airports, metro stations, manufacturing plants, buildings, hotels, commercial complexes, shopping malls, and gated societies. Such solutions can replace biometric attendance devices in offices. “Touch-based biometric systems will slowly phase out because of the risk of infections,” Jha says. Our cities already have such techs assisting law-enforcers. Like the CCTV-powered automated number plate recognition system (ANRS), which got a man arrested in Rajkot. It detected he was out in his car 21 times during the lockdown. But can a CCTV camera enforce social distancing inside retail outlets, larger open markets? Can it sense the body temperature of a shopper? Yes. An AI software in the system would heat-map the area, calculate the distance between shoppers/workers and ring out alarms.

Robot army—they are minimising human-to-human contact in hospitals, offices...

All these are preventive mechanisms. The real battles are raging in the hospitals, where more and more health workers are getting infected. This is where a self-sterilising robot—like in the movies—comes handy. Ah, those adorable droids from the Star Wars—C-3PO, BB8 and R2-DT! Robots have been deployed at Government Stanley Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, to serve food and medicines to COVID-19 patients. Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Government Hospital has enlisted Zafi and Zafi Medic, products of Tiruchi-based Propeller Technologies, to deliver food and medicines to patients in isolation. Kochi’s Asimov Robotics has its KARMI-Bot, an autonomous robot that has an added feature of being able to disinfect the premises using ultra-violet radiation. Sawai Man Singh Government Hospital, Jaipur, has the locally-manufactured humanoid ‘Sona 2.5’, while Delhi firm PerSapien has come up with Minus Corona UV Bot, which disinfects hospitals using ultra-violet light. AIIMS Delhi has tied up with an Indian company for advanced

AI-powered robots—Milagrow iMap 9 and Humanoid ELF—at its advanced COVID-19 ward to promote physical distancing between health workers and infected patients. The Humanoid ELF enables doctors to monitor and interact with patients remotely. Bored patients in isolation wards can also interact with their relatives from time to time through this robot.

Robots have been used in several verticals—to dispense hand sanitiser, carry prepared meals, disinfect streets. These much-loved robots exist mostly to assist rather than replace humans—and like us, they are prone to errors. So, if you bump into the affable Zafi and the hand sanitiser drops, be nice to place it back on her tray. And give way to Zafi Medic when it is pacing down the hallway cradling a plateful of ward supplies.

***

- IIT Guwahati has built drones to disinfect large areas; drones mounted with infrared camera to thermal screen groups without human intervention; drones with PA systems

- IIT Ropar has developed a trunk-shaped device fitted with ultraviolet germicidal irradiation technology, which can be placed at doorsteps to sanitise items brought from outside, including grocery and cash. It can cost less than Rs 500.

- IIT Bombay has developed a “digital stethoscope” that can listen to heartbeats from a distance and record them, minimising the risk of healthcare professionals contracting the novel coronavirus from patients.

- IIT Roorkee and Kanpur have developed low-cost portable ventilators.

- The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has developed portable backpacks for sterilizing public places. The system is capable of disinfecting up to 300 square metres. There is a higher capacity kit mounted on a trolley capable of disinfecting up to 3,000 square metres.

- The Ordnance Factory Board (OFB) has developed two-bed tents for quarantining coronavirus patients in any terrain.

- Udit Kakar, a 20-year-old youngster from Delhi, is making face shields through 3D printers for the ‘frontline warriors’ fighting coronavirus.

- Budhavarapu Sneha, a girl in Telangana, has come up with a device that cautions the user against habits like handshake, touching the face. Wearable like a wristwatch, the device beeps whenever the person involuntarily reaches out for a handshake or touches the face. It will cost Rs 350 apiece.

- Sarthak Jain, 16, from Modern Public School, Shalimar Bagh, New Delhi, has designed an automated touchless doorbell with ultrasonic sensors that detects a person or object within 30 to 50 cm and sets off the buzzer. Doorbells are a medium of transferring virus.

- The National Institute of Technology Karnataka, Surathkal, has turned an old refrigerator into a ‘disinfection chamber’. The makers say 99.9 per cent of microorganisms present in items kept inside it are killed.