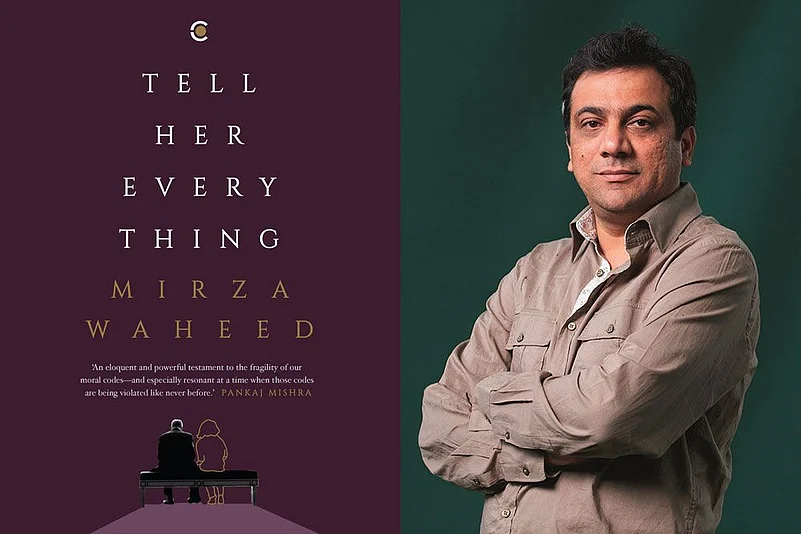

Mirza Waheed has a worn out writer's face. But, he also maintains an air of affable charm. His first book, The Collaborator, was a success and was shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award. His second book, Book Of Gold Leaves, was longlisted for the 2015 Folio Prize and the 2016 DSC Prize for South Asian Literature. Both were based in Kashmir and were about love, loyalty, war, and of course, the Valley.

Now, his third book Tell Her Everything deals with subjects of filial love, morality, paternal bond and a migrant’s pursuit of happiness and the price he pays for it.

Speaking to Outlook after the launch of the book at a hotel in Delhi, Waheed talks about his life as a writer, Kashmir and much more.

A downtown guy from Srinagar, a fact he often refers to, Waheed started his career in Delhi as a journalist with short stints at different places. "I changed a job every year. I worked in publishing with McGrawHill, it was a good training ground," he says. He even worked with a tech magazine and a multimedia startup venture which ran eight issues before shutting shop.

"Then I went to London to work with BBC. All this time, I was reading and writing little things, parking it somewhere but never showing it to anyone. I wasn't confident. So thinking that I could write, it took me another ten years to write."

Asked how exactly he began to write novels, Waheed recalls a particular incident. "I remember one winter night in my little apartment in London… I have a Kashmiri corner, walnut desk and papier mache screen.....I sat and started writing about this boy walking among this long line of dead corpses. It was a long section… I wrote late into the night."

And for his second novel, after his wife told him to "get the novel out before the child”, for once he says, "I stuck to a deadline".

He doesn't remember any specific reason on why he must write a different book, but Waheed says "there are premises, stories, that get in your head, some take hold some don't, and this one goes back many years."

After talking to a friend, who is a medical professional, about the challenges of their job, Waheed started to think "of a man who actually plays by the book, follows rule but wants to be a successful practitioner". That, in turn, became the outline of the protagonist's character in Tell Her Everything.

And since the protagonist is a doctor in a foreign country, a migrant in search of a better life, "how far will he go, how much will he compromise," in pursuit of a better life, is the question that Waheed started to explore. Hence, the story is also about a migrant, "a small-town man gone abroad," explains Waheed.

Set in the late 1980s, the protagonist arrives in England as a young doctor and dreams of being successful. But when he doesn't see himself progressing, he begins to feel inadequate. Frustrated, he looks for better prospects and lands a well-paying job at a hospital. But the catch is that the hospital is also a part of the state and is involved in penal and justice system, that leads him to do "unethical" things.

The book is narrated when the protagonist is retired, in his 60s, and has a very comfortable life but has a realisation of the price he has paid in the pursuit of happiness. Waiting for his daughter to come back, the protagonist, Dr K, makes up his mind to tell her everything, which is from where the novel gets its name.

It's while writing the novel that Waheed got excited about the form it was acquiring. "The rehearsal of the conversation that he wants to have. Within the fictional world, there is also the fictional conversation he has with his daughter". But the protagonist also anticipates her answers or the questions she may ask, prompting endless mind-rehearsals. "None of it is real, it’s all in his head, but how can he get it right?". This ultimately captures the essence of the novel.

Asked how he developed the protagonist's character, "Fours years of my life," he says with a cautious laugh. And immediately interjects, "I am a bit of a method writer, but you have to inhabit the character's mind".

The ambiguity of characters interests Waheed, as he admits that the book was not easy to write. He completed it in little over a year, then did a thorough second draft, and then a third one. "This book is as old as my daughter".

When asked if the third novel, unlike his previous ones, was not based on Kashmir due to fear of being typecast and breaking out of a certain mould, he gives the expression of a man at pain to contain his words, and then carefully says, "the question is also problematic as it suggests that Kashmir cannot contain the entire story of humanity."

Retaining a calm posture, he refers to his boyhood years in downtown Srinagar, "all those things form my sensibility as a writer but that's not all."

On the argument that people often make on social media, of charging commentators like Waheed of being armchair "propagandists" who live comfortable lives in other continents but write about the trouble in Kashmir hence lacking an authentic perspective, the author makes a measured but a forceful argument.

He asserts that the argument is problematic as it is based on the assumption that anyone not living in Kashmir does not have a correct vantage point to write about it. "Somebody who has left Kashmir doesn't have to right to write about Kashmir? That's silly," he stops, composes himself, looks for a better word and says, "No that’s not the right word, its problematic". "If that was the guide book, we would have no writers," says Waheed, resting his case on the issue.

He says that he had to explain to a friend that when he writes about India, there is a distinction between the state and the people. "I felt sad that I have to explain this because it is screamingly obvious."

Talking about his feelings on the situation in Kashmir, he argues that just because a thing is happening in a loop, it doesn't reduce its brutality or pain, and cautions about developing fatigue over it even as one may become inured to the suffering. He believes that the Indian state has not learnt any lesson.

Describing Kashmir as a perfect catalogue of war, Waheed lists the tragedies of the Valley, including but not limited to: state brutality, killings by militants, the exodus of Hindu minority, rapes, and a general deprivation of humanity.

"The Kashmiri sentiment and aspiration for self-determination is still the same," he says while thumping the table, with increasing intensity. "You are trying to crush it by military means by all kinds of brutality, oppression, subjugation. None of it has worked. That means there is a simpler way out," which he suggests is to talk. But talk to whom? "Talk to everyone", he says, "You have to talk to Pakistan," because there is a part of Kashmir under it, "but the primary party remains Kashmiri people."

"India is a party too, of course," he says.

The message for India, according to Waheed, is very clear: "the military solution hasn't worked".

However, Waheed is not convinced that Islamist tendencies of the youth might be taking roots in the Valley, "I like to believe that the fundamental DNA of Kashmir is a moderate soft-core", he says.

He argues that radicalisation is not disconnected from the conflict and can't exist in a vacuum. "You remove the conflict, brutality, the oppression, you remove the reasons for youth finding solace or comfort or sense of identity or belonging in forms of religion whether extreme moderate, it will go," he says confidently, like many Kashmiris who pin hope on a better, multicultural future.

After a short pause, with a straight face, he says, "I am not denying it, but it is not the most vital aspect of Kashmiri situation right now."

Rather, he says, he is concerned about young children being targeted in their homes. "I don't like it at all. It upsets me," he says. "It doesn't suit a democracy to shoot little girls in their eyes who are in their homes," he maintains.

Waheed also talks about his next project, a personal history of Srinagar, a place he says he loves "too much" and misses a lot. He believes it sounds cliched and says he doesn't see himself as a non-fiction writer but seems adamant and enamoured at the prospect of writing such a book.

He also likes to cook and claims to have his own variation of the Kashmiri dish Rogan Josh. "My son loves my food, the rest doesn't matter."

.JPG?w=200&auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max)