For many students on Jadavpur University campus, September 19 had been a routine day. Classes began to wind down at around 5:15 pm, as usual, and after-college co-curricular activities began. Ananyo Brahma, a third-year Economics student, had been attending a session of the university’s quiz club; another student from the English department had been at an aikido class; yet another student, T ANagalakshmi, had been attending a session of the photography club. Around 6:30 pm, however, things started to change.

“The university guards came to the room we were practising aikido in and told us to leave immediately,” said the English student, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “They said there was a crowd gathering outside campus gates.”

Nagalakshmi had gone to get food from a canteen next door to Gate 4 of the University. “All of a sudden, we heard loud noises. I went outside and saw that people had gathered outside the gate, with hockey sticks and lathis, and were yelling at students inside the campus,” she recalled.

Meanwhile, news about a major disturbance started spreading on social media and Brahma became concerned. He and his fellow students decided to close the quiz session earlier than expected. On their way out, they realised all the gates near the UG Arts building had been closed. Gates 3, 4 and 5 of the campus were shut against the rapidly swelling crowd outside, and the students in those areas had been shut inside the campus, with little idea of what was happening and no easy way of getting out.

Around 7:30 pm, Tarit Baran Dash, the differently-abled shop-keeper, whose shop is right beside the gate no 4, was worried. “I could hear the crowd outside getting louder, chanting Jai Shri Ram,” he said. This has been caught on video by students on campus at the time.

The angry crowd, which had lit a fire outside gate no 4 by then, was kept under check by a line of policemen and university security guards. People outside the gates, on their way home from work, colleges and schools, knew something wasn’t right; a video shot outside gate no 4 shows their alarm at what was clearly becoming a heated situation. As the fear built, around 8:15 pm, the crowd broke through the barred gates.

A member of Jadavpur University Press, who had been in the UG Arts building right in front of Gate 4, ran upstairs to hide in darkened classrooms as people rushed in. “We hid in the Bangla department, and we saw the crowd entering through the gate,” they recalled. Video footage of this moment was found on social media. The rampant vandalism and violence that followed that evening soon made headlines around the nation.

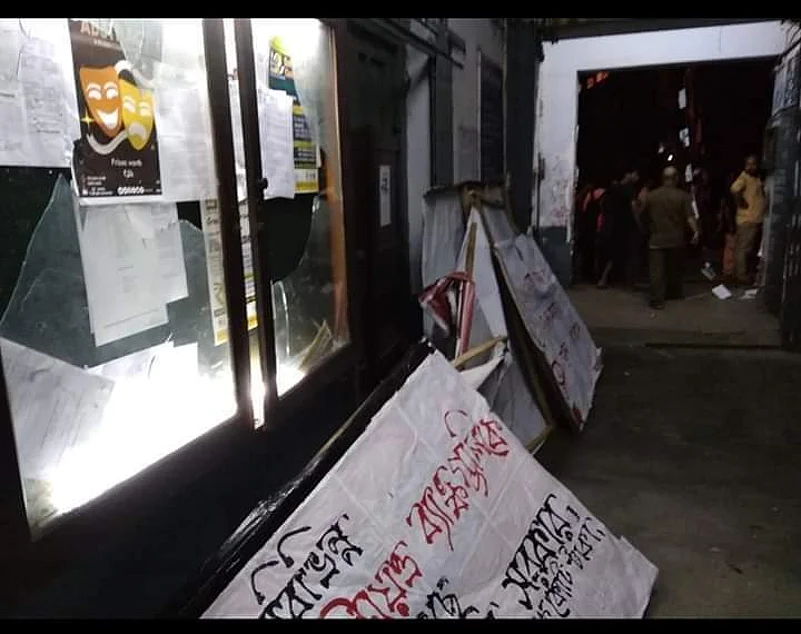

When this reporter visited the University on September 20th afternoon, things looked normal. The cigarette-and-snack shops and tea shops outside the university were in business, as was Tarit’s stationery store. Only the scorch marks on the road outside Gate 4 and the broken contents of the Union Room, gathered outside the door remained as physical reminders of the violence. Inside the room, the fans were hanging limply off the ceiling; the walls were covered with graffiti screaming ‘ABVP’

Tarit da sat behind the counter, talking to visitors who dropped in to inquire about his health. The freshly patched-up wounds on his head and cheek, where he had been hit with pieces of flying glass when his window had been shattered the previous night, became visible when he turned his head.

Two distinct narratives about the incident had emerged on mainstream and social media by then. Predictably, in the post-truth era, they were pitted against each other, with plenty of obfuscation, confusion, well-meaning but misleading information and outright disinformation in the mix.

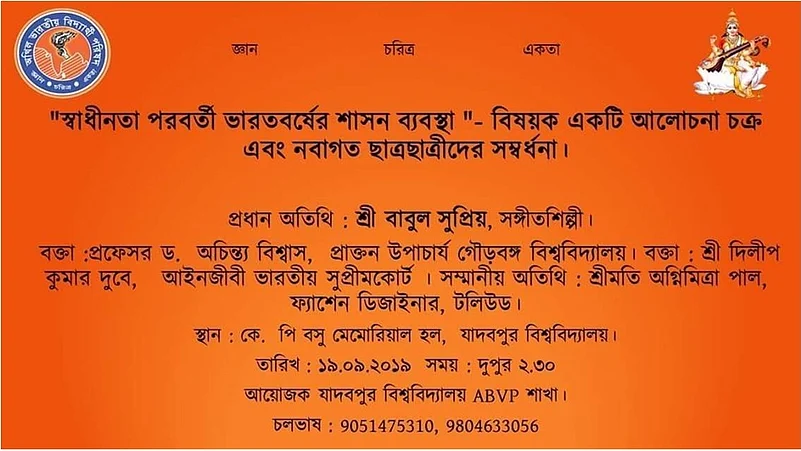

The students of Jadavpur University declared that they had been forcibly and violently stopped from carrying out their democratic right to a peaceful demonstration by the guards that accompanied Union minister Babul Supriyo. Supriyo had been invited to an on-campus Fresher’s event organised by students and members of Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the student wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, on Thursday, 19th September at K P Basu Memorial Hall.

The student members of ABVP, meanwhile, opined that a union minister, who was an invited guest, cannot be prevented from attending an event that had been organized with all the required permissions. They further alleged the students manhandled and heckled the Minister, gheraoed him and refused to let him leave the grounds until he was rescued by the governor of the state himself, forcing his armed security team to retaliate.

At the heart of these narratives was the role media played in furthering misinformation. Large sections of the national media, in a race to break the news, had articles on their websites that were basically copies of one another, possibly obtained through an agency such as the Press Trust of India, which meant that many of them had published reports on the incident without actually visiting the ground or speaking to anyone from the University. No reportage that emerges under such conditions can be either fair or contain nuances and complexities of a given situation -- these didn’t, either, and therefore much of the media failed the students of the university that night.

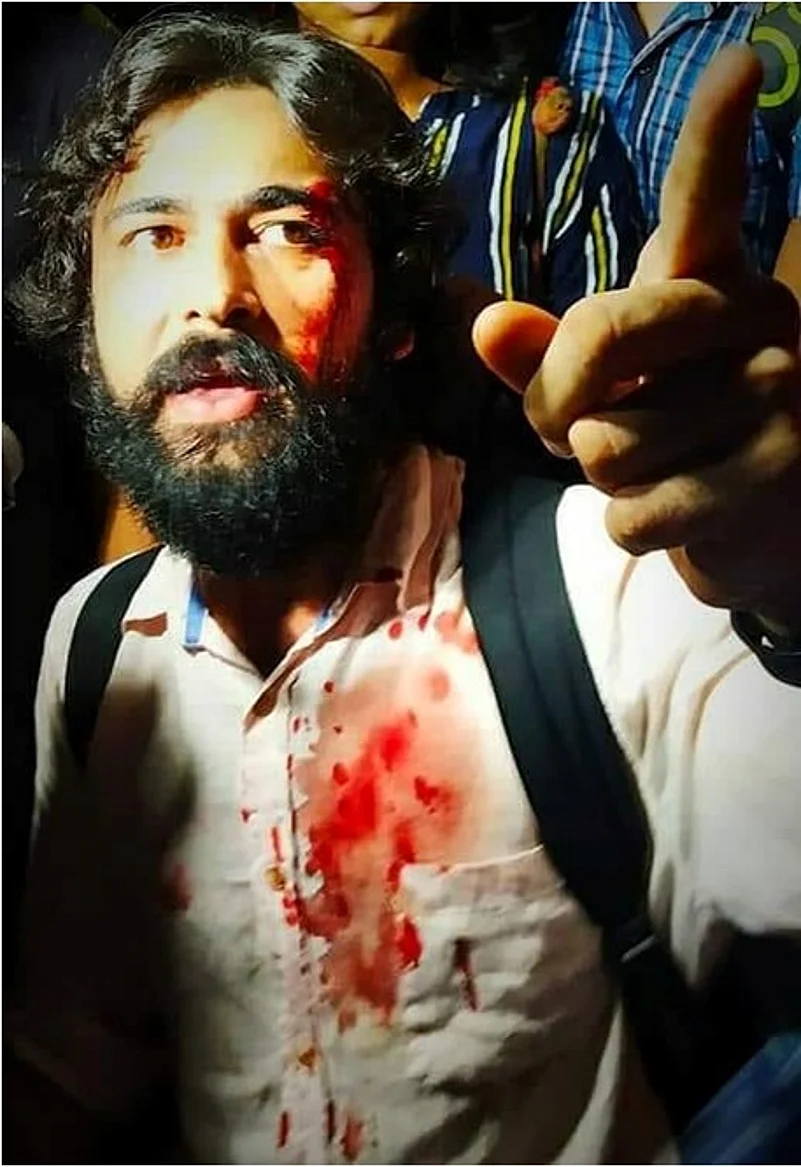

Meanwhile, the fall-out of the evening reached the VC, who attempted to mediate the situation twice, declaring he would rather resign than call the police on students; editors who reported on the story; and the students of the university. Online, students have been subjected to trolling and violent language, including death and rape threats, in comments on a picture of a woman standing next to the minister -- the woman in the picture was not the one who was targetted -- as it emerged later, and she had been misidentified, but she continued to be trolled for it. Pictures of ABVP party members apparently injured during the course of the evening also emerged.

Glass display cases shattered on the ground floor of the UG Arts Building.

Comparative Literature student Pawan Shukla, pictured after violence. Shukla did not respond to requests for comment.

At 4:30 pm on September 20, a protest march, announced on social media and circulated on Whatsapp groups, began as a small procession that snaked its way to Gate 2, picking up more and more people along the way, until one had to sprint to stay ahead of it. As we reached the open ground behind Aurobindo Bhavan, the administrative building of the University, an enormous, waiting crowd greeted it with roars of approval and applause and merged with it to make its way onto the streets.

If the university wanted strength in numbers, it certainly got it. Over 6,000 people, including current and former students, students from other institutions such as Presidency University, The Heritage College and St. Xavier’s University, and even citizens unaffiliated with academic establishments attended in solidarity. Members of many major political organisations on campus attended as well, including Forum for Arts Students, Students Federation of India and Arts Faculty Students' Union.

As the crowd walked along, slogans and songs rent the sky; Ray’s song O rey halla rajar sena, about a pair of musicians who sing to an army about the futility of war, was one of the melodies sung. The song is from Hirak Rajar Deshe- a movie about a tyrannical king being overthrown by a popular revolution.

On September 23, Monday, ABVP held a counter-rally from Golpark to Jadavpur Thana, attended by nearly 2,500 students, according to estimates provided by ABVP. Suranjan Sarkar, a first-year Journalism and Mass Communications student at Jadavpur University who is the State Joint Secretary of the organisation, said, “We wanted to send a deputation to the Vice-Chancellor to ask for better on-campus security for invited guests. On the way, we encountered three police barricades and they did everything in their power to stop us from taking forward our peaceful deputation.”

This time, university professors were at hand to de-escalate the situation. Faculty members formed a human chain from 12 noon to 4 pm with the intent of physically resisting the entry of outsiders to campus. They had taken a similar step earlier in February 2016, when ABVP had organized a march to the university to protest alleged anti-national sloganeering.

Rimi B Chatterjee, associate professor of the English Department, said, “Very few of us professors were even present on the scene on Thursday (September 19) when all of this happened, and we were blindsided. If we had known, we would have been there to help and to control the crowd.” Samantak Das, professor of Comparative Literature, agreed. “Our students, being young and enthusiastic, unfortunately, responded to the politics of provocation, “ he said, noting that while Supriyo seemed to welcome the media attention during the situation, it was still one that was similar to a gherao.

Sarkar, however, denied ABVP’s involvement in the violence and vandalism of the night of September 19. “They set a fire outside their own gate, and we certainly did not break the gate,” he said. “If anything has been vandalised by any other groups, we condemn those actions and do not take responsibility for them.” He refused to confirm that the individuals who vandalised the Union Room were associated with ABVP, saying that anyone can graffiti anything if they choose to.

The irony of such an incident occurring around the fifth anniversary of the Hok Kolorob movement, which was started to protest the unleashing of police violence on dissenting students, was not lost on the students or their teachers. “This cycle of repetition of targeting Jadavpur repeatedly needs to stop. We feel that we are under attack from multiple parties and it’s quite terrifying,” said Nilanjana Gupta, a professor in the English department, speaking the day after BJP’s West Bengal President Dilip Ghosh said that there needs to be a surgical strike on the university.

As evening fell on the sprawling grounds of the university on the day after the violence that affected so many, the vast rally organised in response to the violence at the University returned to gate Number 4. Just outside the gate, shopkeeper Abhijit Halder was gearing up to serve food to the hundreds of hungry dissenters, who made their way to his ‘roll-er dokan’- a shop that serves kathi rolls. Haradhan da, next to him, started handing out bottles of water and soft drinks to the exhausted crowd.

Just then, a girl who had been a part of the rally approached a security guard and a policeman. The two had just sat down on the same bench to eat, having accompanied the rally on its journey. “Excuse me,” she said, politely, and they both moved up the bench to allow her to join them. The three sat eating together in mutually respectful silence as the slogans from the rally faded into the evening air.

The university that has launched a thousand movements and resisted a thousand more remained, for the moment, intact, if not quite unharmed.