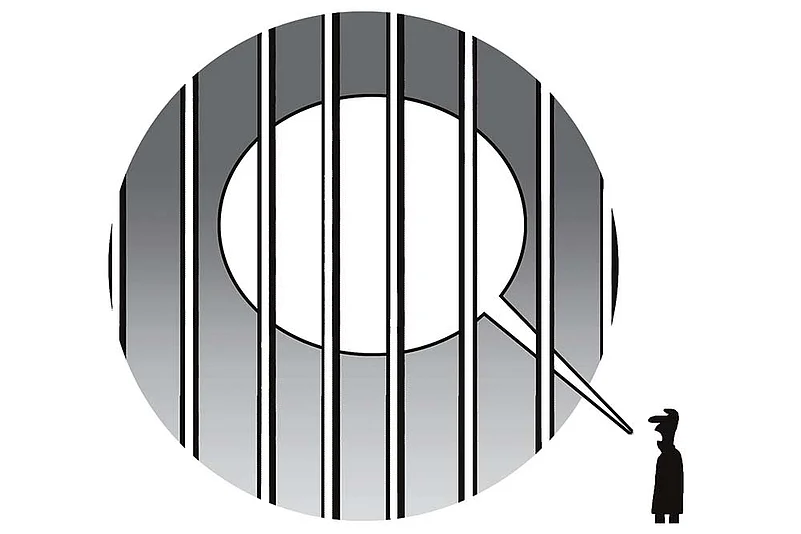

In the dark and dank dungeons of Indian prison, life is a killer, mentally and physically. There are people who chose, or more specifically, driven to the path of crime and finally the long arm of the law catches up with them. And there are a handful, much like our freedom fighters, never scared to sacrifice life for justice, look the administration in the eye and ask questions. In India, might is right, well almost. And when the administration flexes its muscle and tries to gag those seeking truth, sanity is consigned to the backburners.

Young Manipuri journalist Kishorechandra Wangkhem was at the receiving end of a rogue of a government last year. He challenged the sanctity of the National Security Act and ended up behind bars for asking uncomfortable questions on social media. Outlook India was the first to highlight his plight. Wangkhem soon became a subject of national debate. In the first article of this two-part series, 39-year-old Wangkhem talks about his struggle.

Enemy of the State?

I knew I was swimming against the tide but I stood firm on my ground. My wife, Ranjita, visiting me at Sajiwa Central Jail, asked me what I had decided. I said I would never bow down, for I had done no wrong. It seemed everyone or everything was against me and my family. It is the truth that prevails in the end; and justice has been served. But the imminence of light doesn’t always feel like a guaranteed thing when you’re stuck in the tunnel. All hell had broken loose on November 19, 2018, when I criticised the ruling party and its government on social media for their lack of concern for the history, religion and culture of the region’s ethnic minorities. Yes, in my pique, I’d allowed myself some expletives…I realise I could have worded it in a better way. Anyway, I was arrested the next day, charged with sedition and defamation and remanded to six days’ police custody.

It seemed unreal—and luckily, temporary. On November 26, the CJM Imphal West granted me bail against the 15-day judicial remand sought by the authorities. My family breathed a sigh of relief, and I too felt the trauma slowly ebbing away. But the very next day, plainclothes police arrived at my house and picked me up—and I found myself sitting in the office of the Additional SP (Law and Order), Imphal West, for nearly five hours. I came to know I was being detained under the National Security Act (NSA) only after I was taken to Sajiwa.

The Mind is a Prison

I would not say life in jail is as harsh as it’s assumed generally. I encountered no physical harassment. Inmates spend time with sundry activities during the day and early evening—time glides by silently. It’s when the lights are turned off after 9 in the evening that the mind starts thinking. I might have asked myself millions of questions. I thought of the progress of the case, I thought of my family. Whenever I met them once in a fortnight, they would talk about the threats, blank calls, lewd messages, social stigma and isolation. Despite being separated by force, we shared that unspeakable mental trauma. It’s impossible to communicate that sense of hope itself expiring. The one thing that always made me cry was when I thought of my elder daughter. I couldn’t keep myself from breaking down even when I first saw her after my release.

(The writer, a journalist, was jailed for 133 days under NSA for criticising the government)

(Next:The Curse Of Being An Ethnic Minority And A Sissy Media)