Her hollow, dark-circled eyes stand out like her jutting cheekbones. They are the most prominent features of her bony face with its depressed cheeks. The creases on the forehead speak of a stressed, worried life. The head with its unkempt hair tied loosely in a bun looks large above the haggardness of her face. Yogita Gaikwad is a tall woman. Her emaciated frame is bent forward and looks frail to carry the weight of the 35-year-old body. It is a body that needs nourishment—a luxury she cannot afford.

Yogita lives in the Bhoot Bangla slums in Ghatkopar’s Ramabai Ambedkar Nagar in the eastern suburbs of Mumbai. “I don’t eat every day. My children need the food, so I skip meals. When I am hungry, I drink water,” Yogita tells Outlook. She stares vacantly into the space in front of her for a while before she speaks again. “I work as a maid in two houses and earn Rs 2,500 per month. My husband works as a security guard and earns Rs 6,000 a month. He lives near his work site and comes home once every six months. He rarely gives me any money,” mumbles an emotional Yogita. From her meagre earnings, she pays Rs 2,500 as rent for her house and Rs 500 as electricity charges. She is heavily in debt—she has borrowed money from the places she works. “I have to pay off Rs 35,000 I borrowed. So, my salary is deducted. I get very less money every month. I have to borrow if I have to feed my children. I don’t know how long this will go on,” says a misty-eyed Yogita. Her only desire is to eat a full meal with her children.

The pandemic has been tough on the illiterate or less educated workforce employed as casual labour on daily wages. Though this labour market has contracted since the pandemic, men have been slightly more fortunate than women in finding casual work. The population of unorganised workers is significantly high among agricultural workers, construction labourers and home-based workers. Women usually go in for temporary and standby jobs as people are unwilling to employ them. Women’s employment is high in the unorganised sector, particularly as household helpers, farm helpers and as construction labourers.

A slum in Dharavi. Photographs: Getty Images

However, due to the pandemic and the ensuing job losses, fewer women get employment nowadays. “If a man and a woman come to me for a job, I will employ the man. They can work long hours, women cannot. They have their own households to look after,” says Rohit Chakrapani, a labour contractor. A supplier of labour from the unorganised sector, Chakrapani says the number of the unemployed is shocking. Since the Covid lockdowns, workers in this sector are faced with longer work hours, less pay and suspension of the minimum wages clause. “If I am not making enough money, how can I supply labour at a higher cost,” Chakrapani tells Outlook. The present situation has worsened the pre-existing disparity in the labour market.

Srikala is a commercial sex worker living in Mumbai’s Kamatipura redlight area. She is middle-aged, short with a thick-set body. She is from Karnataka and came to live in Kamatipura some years ago. “I am ugly, so I would not get a lot of clients. I would stand on the roadside near CST station and pick up clients there. On days I did not feel like travelling to CST, I would solicit clients in Kamatipura,” says Srikala. The minimum she charged from a client was Rs 150 for an hour of intimacy. On a “good” day of business, Srikala earned Rs 1,000-1,500 a day.

The years of the pandemic have taken their toll on her health and her finances. With no clients coming to her kholis (rooms), Srikala has plummeted into abject poverty. However, during the lockdown few clients did brave the walk to the kholi, but the police clampdown scared even these few away. “Daru ka dukaan bandh tha. Hamare paas shudhi mey kaun aayega, daru peekar aayega. Daru nahi dhandha nahi. Bheek maangke khate,” (The liquor shops were shut. No one comes to us in their senses, they come in an inebriated state. No liquor so no business. I beg for a meal), narrates Srikala. With no income, she plans to move out of Kamatipura and lose herself in the vastness of Mumbai.

Social worker Meena Seshu has been working for the upliftment of commercial sex workers, including male, female and transgender, for several decades. She has seen their highs and lows but the present-day situation is harrowing and never-ending. “Theirs is a physical job. They invest emotions into that job. They develop emotional relationships. The lockdown affected their relationships and they lost a lot. It was not just a job they lost,” Meena tells Outlook. According to Meena, commercial sex workers have been systematically targeted by police in various parts of Maharashtra. “During the lockdown they raided the homes of these sex workers in Nagpur, Jalgaon, Nashik and other parts of the state. The entire redlight areas in various places have been barricaded. Clients are not allowed to enter. If they do, they are harassed by the police. The loss of income is huge,” Meena adds.

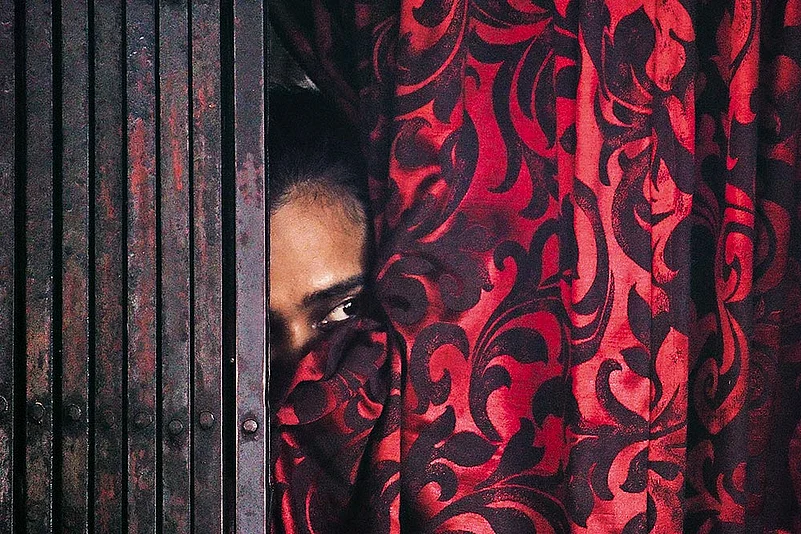

Mumbai Mirror A sex worker peers from behind a curtain. Photographs: Getty Images

The police action is in stark contradiction to the reach-out programmes implemented by the Maha Vikas Aghadi government during the lockdown. An estimated Rs 49.8 crore was allocated by the state government for commercial sex workers under the Covid-care programmes. Various departments of the state government continue to be a part of this Covid care implementation. “The police action is at a tangent with the help being extended by the government. When there are ear-marked redlight zones, this community must be allowed to work,” says Meena.

Real estate development plans in Mumbai include redevelopment of the Kamatipura area. With developers keen on getting a slice of this development project, the sex workers in the area are feeling the pressure to relocate. Sources say that fearing police raids, arrests and imprisonment, many sex workers have left Kamatipura. “They are looking for safer places without police brutality, which means they would be vulnerable to criminals and gangs. This is a very scary situation,” says one source.

A study conducted by the India Forum indicates that in 2018-2019, about 52 per cent of the labour force was self-employed, 24 per cent were casual labourers without financial security and the remaining 24 per cent were workers with regular wages. The illiterate or less educated casual workers with low paid unstable jobs and facing lay-offs have been worst affected, said those in the know. In fact, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) predicted 112 million job losses in April-May 2020.

Baana has been a ragpicker for several years—she has forgotten the exact mishap that made her a ragpicker. She lives alone on a footpath in Thane’s Wagle Estate area. A tarpaulin sheet passes off as her home. When she is not at “home” the tarpaulin sheet is bundled up and kept on the footpath along with some of her meagre belongings that include a sari, an under skirt and a blouse. When she’s “home” the ends of the tarpaulin sheet are tied to the wire meshing atop a wall touching the footpath. The other ends are secured to the ground with stones. A strong gust of wind will blow away the tarpaulin. “I start very early and go to the garbage bins near the hospital (Thane Civil Hospital). I get a lot of things. I sell them and get some money. I buy food with that money. When my clothes tear, I ask a security guard of a building close by to help me. He asks some people and I get one or two clothes. He also gives me water to drink,” says Baana.

Her weather-beaten wrinkled face needs a wash, like the rest of her. The Sulabh Sauchalay, close by, is a great help. It is a paid service, for Rs 2 she can use the toilet and for Rs 5 can take a bath. Baana can wash her clothes for another Rs 10. “I bathe in the evening. But not every day,” she said.

For Yogita, Srikala and Baana and the millions like them, poverty is a constant—they sleep with it, wake up and live with it. They are not a vote bank, nor do they figure in any welfare plans of the state or central governments. Neither are they part of government budgets, census or statistics. Each is connected to the other through the different degrees of poverty. Adrian David and his mother Sabrina have been trying to empower people from the poorest slums in Mumbai who are at the lowermost rung of the poverty graph. Working closely with a number of NGOs, the Davids have been able to generate some jobs for the slum-dwellers of Shivaji Nagar, Govandi and Ramabai Nagar. “It is tough. All they desire is one meal, even if that is such a luxury for them. There is so much poverty in these slums,” Adrian tells Outlook.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Living on the Edge")

By Haima Deshpande in Mumbai