19-year-old Nadira Mondal wakes up at the crack of dawn at her home in Kalidanga village in West Bengal and the first thing on her to-do list is to set the lesson plan for her classes. Not for her own classes but the ones she gives to the kids in her village. A student herself, Nadira started teaching a group of underprivileged children in her neighbourhood during the first wave of the pandemic in 2020 and hasn't stopped since. Her students consisted of all ages but most of them had minimal reading ability. They were also the ones who could not afford online classes and were instead forced out of school when the pandemic hit.

“I have around 30 students. I teach them basic Science, Maths, Geography, History and English. Not all of them are on the same levels of literacy so I give special attention to some and select different coursework for others,” Nadira says.

(Nadira teaching her students at a makeshift school in Kalidanga village | Credit: Rakhi Bose)

Currently pursuing her graduate degree from home due to the lockdown, Nadira says she borrows books from her college library and friends to help the students. She also receives help from a local NGO called Education For All. Though not a professional teacher yet, Nadira has big dreams for the children of her village. “I want to continue teaching because education is the only weapon the underprivileged have to succeed in life,” the teenager tells Outlook. Nadira hopes to one day get a professional degree in teaching and become an inspiration for other girls in her village. Perhaps she knows that she already is.

Almost all of the girls in Nadira’s class said they wanted to become teachers too when they grew up. They eyed Nadira adoringly and hid behind her dupatta when the questions got too tough.

The picture, though a romantic projection of human resilience and perseverance through tough times, somewhat belies the true condition of teachers in the nation. In their hopes to become educators, the girls of Kalidanga are yet to find out that the life of a professional teacher in India - especially rural India - is mired in unfair and often invisible hardships.

Underpaid and Neglected

Anita Sahai* is a primary school teacher working with a reputed private school in Kolkata. As a certified professional for 12 years, Anita has often felt that much of the hard work put in by teachers was often invisibilized by society. The pandemic made it worse.

"The first move on part of school management was to cut salaries. Some teachers like me and staff were not paid for months and the dues still remain. If we complained, we were asked to leave," Anita confides on condition of anonymity. She feels lucky she still has a job at a time when thousands of teachers have lost theirs. "It was not just because of schools closing. Even when they opened, most of us had to adapt to the online mode on our own with no guidance or resources. Many teachers don't own laptops, smartphones or 24-hour internet connections. I myself had to buy a second-hand laptop to give online classes," Anita adds.

The Covid-19 pandemic has deeply impacted the 9.43 million school teachers in India working across private and public sector schools as well as unaided and education department-run institutions. But despite the sizeable amount of the demographic and the hardships they have suffered since 2020, school teachers and teaching as a profession receive negligible support from the public or private sector, resulting in the widespread vulnerability of teachers.

The National Education Policy 2020 has laid fresh impetus on the importance of teachers in the education system. However, teachers continue to remain one of the lowest-paid public servants in the country. UNESCO’s recent State of the Education Report for India 2020, found that 42 per cent of the teachers across private and government sectors in India were working without a contract and earning an average salary under Rs 10,000 a month. Only 8 per cent of teachers have contracts spanning between one and two years. The problem is worse in private schools were as much as 69 per cent are working without contracts, leaving them without any benefits and vulnerable to unemployment without notice, salary cuts, inhuman working conditions or deferred pay.

The average monthly household consumption expenditure for all teachers is estimated to be Rs 14,276, meaning that most teachers need to supplement their teaching professions with other jobs to make a living.

(Source: CETE research team’s calculations based on PLFS 2018/19 data)

One of the shocking highlights of the study was the discrepancy between private and public school teachers. Private primary and general secondary school teachers were paid nearly 43 percent less than government school teachers.

“It is shocking to find such discrepancies in the system. While many read this data as government school teachers being overpaid, the reality is that private school teachers are underpaid,” Prof Padma M. Sarangapani, lead author of the report and Chairperson, Centre of Excellence in Teacher Education at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, tells Outlook.

The study also found that 50 per cent of the total teaching workforce in the country were women. Sarangapani feels that this is another reason for the exploitation of teachers, especially in the private sector. “Employers often take advantage of the financial and social condition of women and also the fact that teaching is probably their second income, especially in rural schools, where they will settle for lower wages,” she says.

For every ten teachers in the government sector, there are seven working in the private sector. “That is a significantly large number. There is an immediate need to look at the working conditions of teachers in the private sector and institute minimum standard or terms of services that apply to all teachers in both public and private sector schools,” M. Sarangapani says.

Not Enough Teachers

While the number of teachers has increased since 2013, several states across India continue to face a shortage of teachers, especially in rural India. There are a whopping 110,971 single-teacher schools in India which make up 7.15 per cent of all schools in the country. 89 per cent of these single-teacher schools are in rural areas. States with a high percentage of single-teacher schools include Arunachal Pradesh (18.22 per cent), Goa (16.08 per cent), Telangana (15.71 per cent), Andhra Pradesh (14.4 per cent), Jharkhand (13.81 per cent), Uttarakhand (13.64 per cent), Madhya Pradesh ( 13.08 per cent), Rajasthan (10.08 per cent).

The report highlighted that as per the current Pupil-Teacher Ratio, the estimated number of schools with vacancies at the country level stands at 301,166, or 19 per cent of all schools. States with vacancies higher than the national average include Bihar at 56.03 per cent, Jharkhand at 39.98 per cent, Uttar Pradesh at 32.66 per cent, Delhi at 21.94 per cent and Madhya Pradesh at 21.66 per cent. Based on the PTR of 35:1, the total additional teacher requirement is found to be about 1,116,846. 69 per cent of the total additional teacher requirement is in rural areas. States with large requirements include Uttar Pradesh (320,000), and Bihar (220,000), followed by Jharkhand, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and West Bengal (between 60,000 and 80,000).

The data, while reflecting a need to increase teachers, also draws attention to the issues of distribution and teacher deployment.

Dr Parth J Shah, director at Indian School Of Public Policy blames the "arbitrary" hiring process for government teaching positions in India. "In the public sector, teachers are hired as per the requirements of the state and not the school," Shah tells Outlook over the phone. The educator adds that in most cases, applicants for government teaching posts have no idea which state they will be shipped off to or even what subject they will be teaching. Shah feels that arbitrary hiring not only affects the PTR but also the quality of teaching as it often leaves teachers blindsided. "Imagine applying for a job and not knowing what it is or where you will be posted," he muses.

Unfit to Teach?

Poor or unregulated working conditions and low PTR are not the only problems plaguing the teaching infrastructure in India.

The availability of a professionally qualified teacher is now a mandated requirement for a school to be recognized. However, a significant share of teachers in the preprimary, primary and upper primary levels neither possess an academic degree from a college (a graduate or a postgraduate degree) nor a professional degree (such as a Bachelor of Education [B.Ed.], or even certificate in basic teachers training).

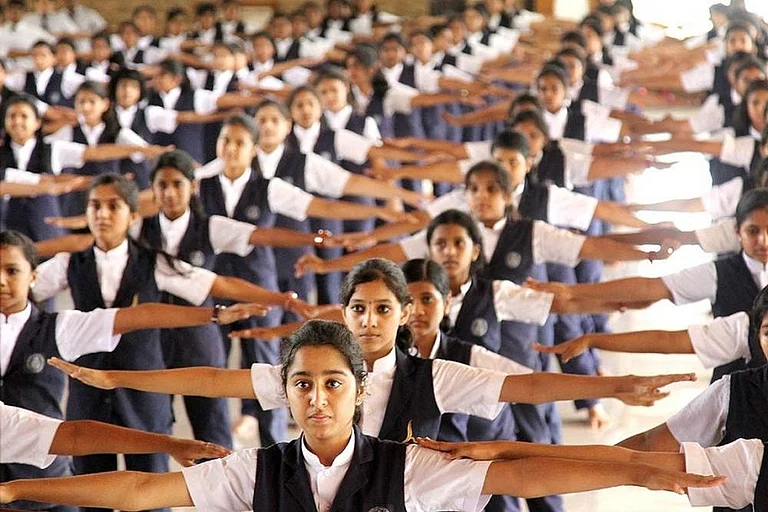

(A general secondary teacher teaching a class full of students | Credit: UNESCO)

North-eastern states like Tripura had the highest number of under-qualified primary school teachers, followed by Meghalaya and Sikkim. A majority of these were from private unaided schools or institutions maintained by the Education Department.

Only 0.22 per cent of the teachers across India had special needs education training. 18 per cent were trained as ‘early childhood education teachers, 39 per cent were trained as primary school teachers, and a majority of teachers were trained as secondary school teachers. Only 0.42 per cent were equipped to give vocational skill training.

Lack of training often stands between a teacher and professional success, resulting not just in low wages but also a loss of dignity and professional identity. When planning interventions and training programmes for teachers, it is thus important to focus on courses and curricula that build not just teaching credibility but also the autonomy and dignity of teachers.

“Wherever teachers have taken the economy and resources into their own hands and come up with local interventions, we have seen results, both in terms of alleviating the condition of teachers as well as for improving standards of education among students,” TISS' Sarangapani says.

In this view, one of the recommendations that educators like Sarangapani and Shah make is to create training programs that value the professional autonomy of teachers and develop career pathways for the teachers to grow as professionals. Developing a dignified attitude toward teaching and respecting the professional identity and autonomy of teachers is key to attracting more and more young and educated girls like Nadira from Bilaspur to pursue teaching, not just from a sense of civic duty but also with the aim of becoming successful professionals.

However, individual players or the private sector cannot be expected to bear the burden of reforming the teaching system.

While the government of India has laid focus on teachers through the NEP, the education sector in India continues to be dominated by private players. Almost 95 per cent of the educational institutions in India are owned by the private sector.

“For bringing in real changes, it is not enough to rely on the private sector. The government has to come forward and take responsibility for investing in teaching and teachers, a demographic that the country relies so heavily upon for providing quality professionals,” Sarangapani concludes.