In the run-up to elections, the shrill anchors, piercing jibes and relentless arguments of primetime television become even more vicious. Researchers find media discourse increasingly polarised and biased around polls. But are viewers in Delhi conscious of this polarisation and does it affect their confidence in journalists? These are some of the questions the Centre for Media Studies (CMS) Media Lab investigated in a survey of 500 people in Delhi after the assembly elections.

Contrary to the perception that English media play a significant role in Indian politics, Hindi channels and newspapers continue to be the primary source of political news for Delhi residents. In spite of falling viewership, television (92 per cent) remains the main source of political information, followed by newspapers (51 per cent) and social media (44 per cent). However, most respondents listed multiple media (75 per cent mentioned two or more) as their source of information on national and international politics.

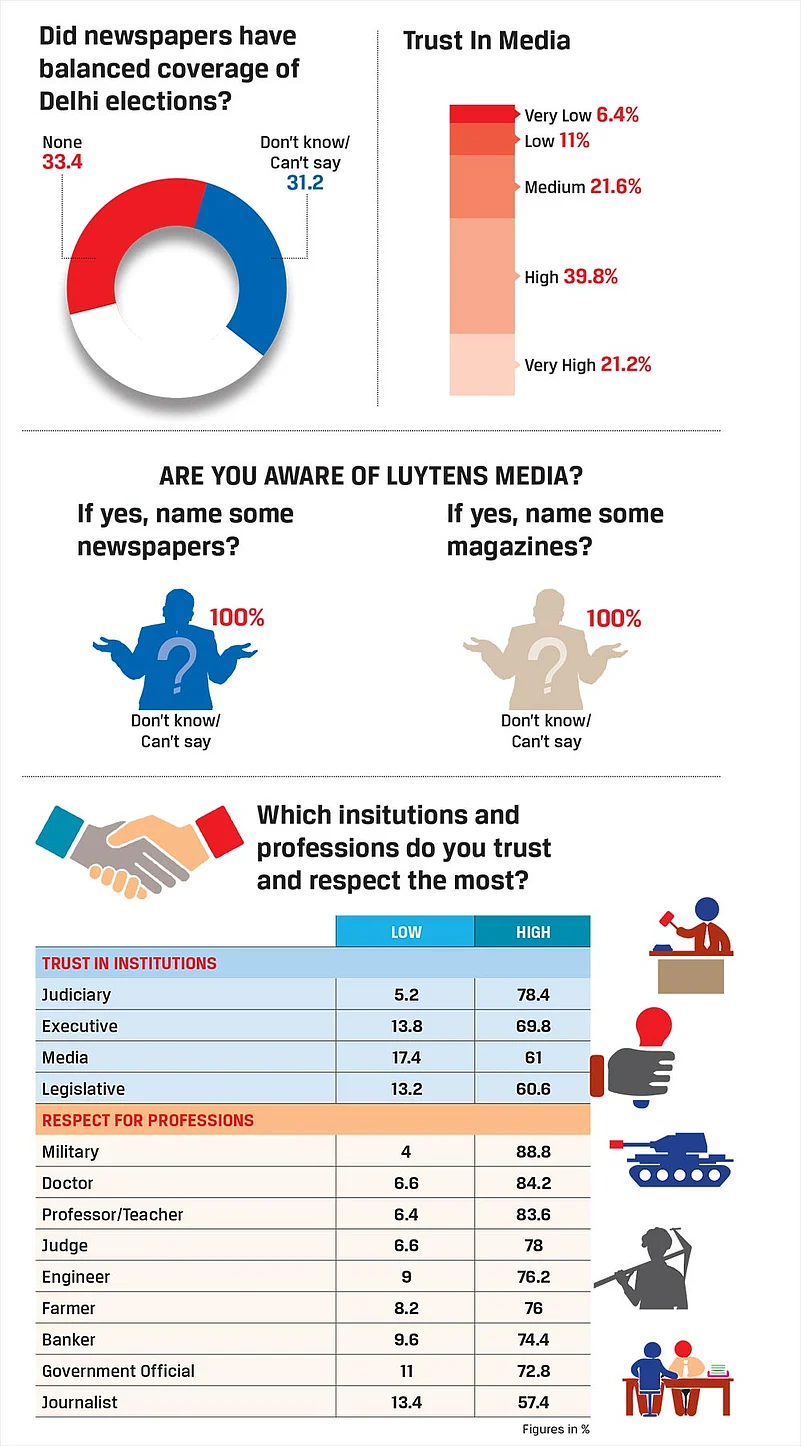

People in Delhi regard television as the most trustworthy medium (63 per cent) for news, followed by newspapers and social media (both 16 per cent). Perhaps the 24/7 news cycle makes it more dependable, especially during elections. While more younger respondents have reported social media as trustworthy compared to other age groups, trust in newspapers and TV channels increases with the age of the respondents. Interestingly, only 53 per cent could name a newspaper they considered trustworthy as compared to 93 per cent for television channels, 12 per cent for online media and 34 per cent for social media.

While most respondents said that the media is ‘biased’, they could not identify the brands they thought were biased. Almost 90 per cent could not name a ‘biased’ newspaper. The corresponding figures for television channels, online media and social media are 42 per cent, 100 per cent and 67 per cent.

Those who discontinued consuming certain outlets or changed preferences in the past year did not have any significant reasons for doing so, though a few mentioned bias in content, such as pro-government coverage, and too many advertisements. While it is easy to switch between different offerings on television by simply changing channels, changing or discontinuing newspapers requires some deliberate consideration or effort. That may be a reason why people don’t switch publications despite uncertainty about their trustworthiness.

We also surveyed the trust the four pillars of democracy evoked among Delhi residents. Only 60 per cent have a high level of trust in the legislature. The media was just a notch above at 61 per cent. The executive (70 per cent) and the judiciary (78 per cent) fared better. While journalism does not rank among the most highly respected professions—military, teacher, farmer, doctor and engineer—they are more highly regarded than politicians, police officers and actors.

Interestingly, just three people in the survey could understand what Lutyens media means. Clearly, the debates regarding the perceived elitist bent of certain media has not percolated down to the larger audience in Delhi. The significant number of people responding that they do not know whether the media is biased or trustworthy needs further studies, especially in the case of emerging online news platforms. Overall, visual media continue to sway viewers and are the primary source of news for most people. As they say, seeing is believing.

ALSO READ: How Many Acres Of Print Does A Baron Need?

(The author is founder member and director-general of CMS. Views are personal.)