Contrary to the image of hospitals as sterile dens of despair, the paediatric ward at Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai has an air of unbridled cheer. Dr Laff-a-lot sports a red bulbuous nose, yellow wig and waistcoat dotted with smileys. His vibrant outfit stands out amidst the muted colours of the ward. The moment he entered, children broke into laughter and began clapping. “Dr Laff-a-lot is here,” together they yelled, excitedly.

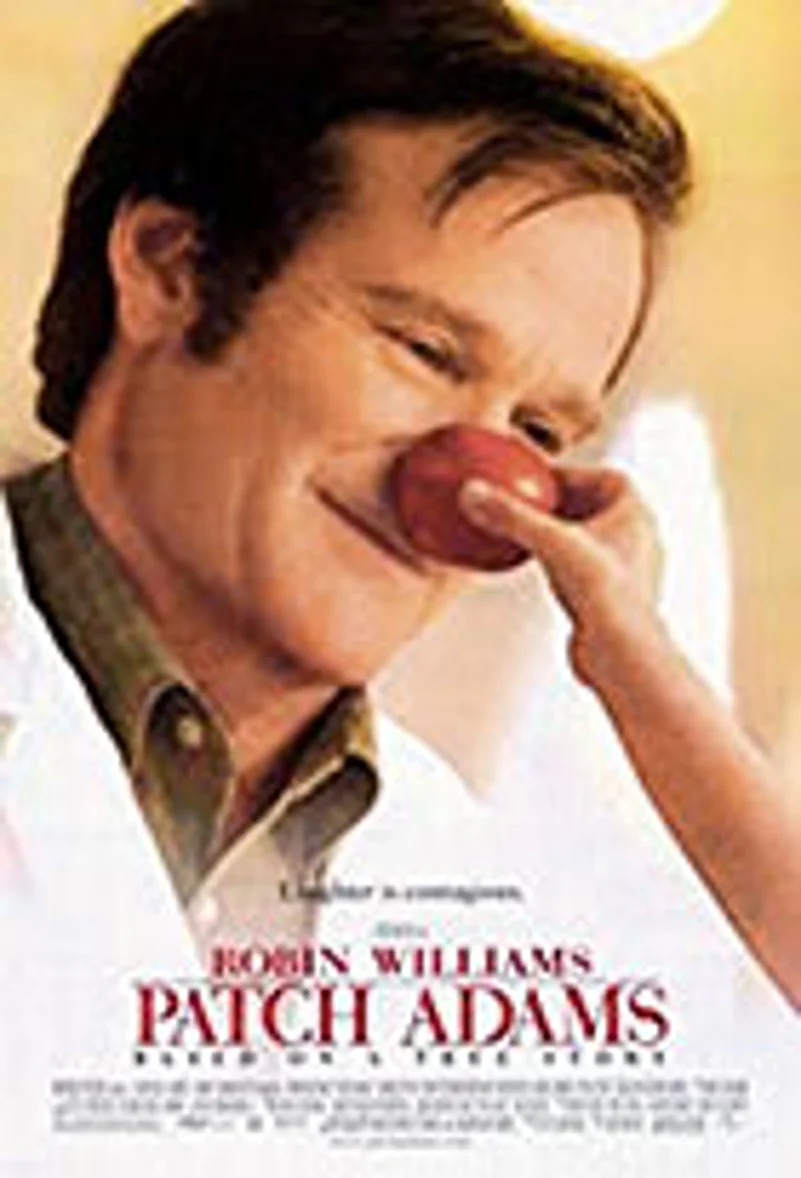

Dr Laff-a-lot, Pravin Tulpule’s alias, is a 58-year-old medical clown in Mumbai. He uses storytelling, magic and clowning techniques to help reduce pain and the stress of hospitalisation, and help people cope with their condition. Although clown doctors cannot cure diseases, they provide emotional succour. Most hospitals focus on the physical health of patients and tend to neglect mental health. Medical clowning fills this void. One of the most celebrated clown doctors is Patch Adams, whom Robin Williams immortalised in an eponymous film. Adams pioneered the therapy in the 1970s, but India is catching up with it only now and it is not widespread still.

“Dr Laff-a-Lot is my clown name when I visit hospitals and patients. Otherwise, I masquerade as Happy the Clown,” says Tulpule, the Mumbaikar spreading joy after voluntary retirement from the Indian Navy. It’s just that the sailor always wanted to be a clown. “Both these characters are about 20 years old. My stage name is my ice-breaker. It amuses people and makes them curious about me.” Shak-espeare had Falstaff, remember?

Pravin Tulpule of Mumbai.

When he was considering forsaking his government job, his family became apprehensive and many called him an idiot. But an encounter with a terminally ill child convinced Tulpule to pursue his passion. “In 2000, I used to perform for kids suffering from cancer,” he recalls. “A child who was very attached to me passed away. I later found out that the kid harboured a desire to meet a clown and I had fulfilled that wish.”

Since then, he has been visiting hospitals, old-age homes, orphanages, and shelters for the HIV-affected and the destitute. “I try to stay calm and talk to patients and their families. I never discuss their ailments or the length of their stay in the hospital. Instead, I involve them with games,” says Tulpule. “Empathy and sensitivity are paramount when one is dealing with patients and their kin. I try to break the stereotype that clowns poke fun at others. On the contrary, I offer them a ready target to laugh at.”

Medical clowns come from diverse backgrounds. At the paediatric oncology ward in Apollo Hospital, Delhi, you are likely to bump into Sheetal Agarwal, 34. Dr Smile, as she is commonly known, lives up to her adopted name. She always had been chipper, a cheerful personality, but never knew or thought that her contagious smile, laughter, guffaw could also heal. Sheetal was a sociology lecturer in a college before she became a clown. She took permission from the Delhi health ministry to clown around at Chacha Nehru Bal Chikitsalaya with six volunteers. The experience was so rewarding that she transitioned from a weekend clown to fulltime joker, and set up the NGO, Clownselors.

Pravin Tulpule at Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai.

For many children, medical clowning has led to breakthroughs in recovery. Preetika Garg, a 42-year-old clown in Delhi, recounts one such incident. “A four-year-old girl was very sad after her surgery. I tried to engage her with my regular antics, but nothing worked. Then I took out a wooden toy with five hens bobbing their heads to peck at rice. Captivated by the toy, she gave out a smile.”

Lately, medical clowning is becoming a career option and many institutes are providing professional instruction. Fif Fernandez, one of the founders of the MediClown Academy in Pondicherry, seeks to train people to become “clown doctors” and establish it as a recognised profession. “India has one of the highest rates of stress, depression and suicides in the world,” she says. We want to lower this by sharing joy, playfulness, mindfulness and love. We want to create heart-to-heart connections to transform and humanise healthcare, education, organisations and businesses across India, and nurture a healthy and happy India for all.”

Hamish Boyd and Fif Fernandez of MediClown Academy, Pondicherry.

What is a typical day for a medical clown like? “I start preparing the evening before the session,” says Sheetal. “I take a headcount of volunteers, sanitise accessories such as wigs and hats, and sort out the props such as doctor’s coats, stethoscopes, mock injections, thermometers, smiley hammers, puppets, balls, balloons and rattles.” On the day of the performance, she reconfirms that the volunteers are participating, coordinates with the hospital or care centre about the location and logistics, and plans the antics.

Sheetal Agarwal at Apollo Hospital, Delhi.

At the venue, they have to be sensitive of the surroundings and keep their voice low. Selfies are not allowed. To avoid spreading infections, they are not supposed to touch or hug patients. In consonance with medical guidelines, they avoid the rooms where patients are in a critical condition. After the session, they exchange their experiences, sometimes followed by group lunch. “Before going to bed, I reflect on the day and express gratitude for being able to share happiness and receive blessings,” says Sheetal. I remain ‘smile hungover’ till the next session.”

Some days are a breeze. Some can be taxing, depending on the children. “There are times when we are stressed, but we ensure that it doesn’t affect our work,” declares Sheetal. As they say, the show must go on.