In government circles, they’ve given the blueprint for Kashmir a snazzy name: ‘The MSD Plan’. That’s short for Modi-Shah-Doval. The last-named, National Security Advisor Ajit Doval, is a man who likes to be known both for his periscope view of things, and for his passion for the nitty-gritty and hands-on fieldwork. The design and architecture of the present security blanket over Kashmir has his imprint. Doval had made regular visits to the Valley prior to the momentous decision on Article 370 and bifurcation. On his table were case-studies of past protests in the Valley that had spiralled out of control—the 2008 Amarnath land transfer controversy, the 2010 summer of unrest following an alleged fake encounter by the army, and the prolonged violent uprising in 2016 after the killing of Burhan Wani.

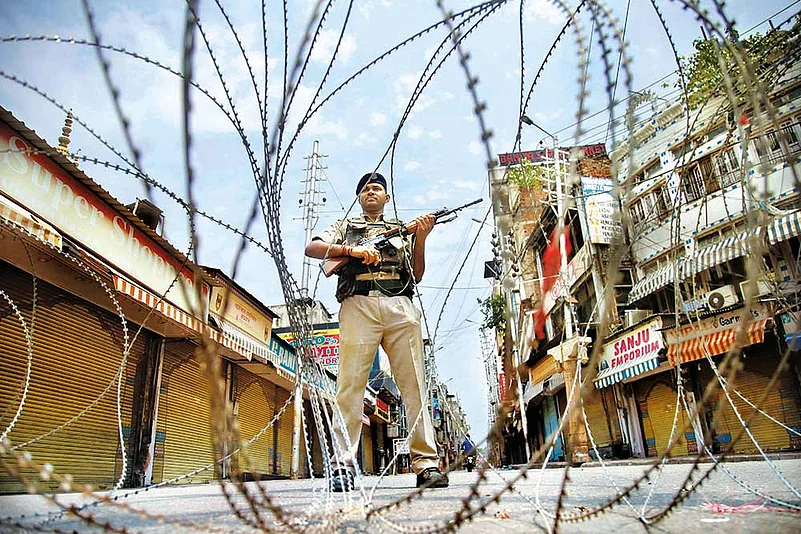

All those agitations had seen clashes between protesters and security forces that left over 150 dead and hundreds wounded. This is what Doval wanted to avoid at any cost. A series of hard decisions flowed from that logic: the suspension of phone and internet services; the imposition of Section 144 along with a substantial infusion of additional security forces; and taking local political leaders, who could become rallying points of protests, out of circulation. Separatist leaders, including those belonging to the Hurriyat Conference, had already been marginalised or arrested. Popular anger may have yearned for release and expression, but Kashmir simply had to hold its breath.

Doval landed in the tense Valley on August 5—the day Union home minister Amit Shah announced the move on Kashmir in Parliament—and personally monitored the ground situation for 11 days. The situation has not eased, nor has his hawk-eyed vigil. At one of his meetings, the NSA is believed to have described the government’s Kashmir action as a “bloodless coup”. It has remained relatively bloodless so far, undoubtedly because of the heavy presence of security forces. Nearly 50,000 additional troops have been sent to Kashmir from July-end, days before history and geography were to be rewritten. This is over and above the 1,20,000-plus personnel of central armed police forces (CAPF) already stationed in the Valley, including men from the CRPF, BSF, CISF, Sashastra Seema Bal (SSB) and ITBP. That figure was already higher than usual. At any given time, the CAPF strength in Kashmir is around 80,000. It reached 1.2 lakh because an additional 40,000 men had been deployed to secure the Amarnath Yatra.

In addition, of course, there’s the army. There are believed to be over 5,00,000 army jawans in what was the state of Jammu and Kashmir, securing the border and LoC and manning other key bases. Nobody in the army or the home ministry (MHA)—the supervising authority for all CAPFs—is willing to give an exact figure of force deployment. It is estimated to be around 7,00,000 and is not likely to be scaled down anytime soon. By ballpark estimates, certainly from the critics, it’s often cited as “one of the highest in the world”, though there’s an essential greyness there.

Even so, several security experts feel these levels of deployment may not be sustainable in Jammu and Kashmir for a prolonged period, and that the government must calibrate its long-term plans sooner rather than later. Former army chief General V.P. Malik, who led the army during the 1999 Kargil war, believes such heavy deployment of forces is “neither sustainable nor in national interest”. He concedes the current situation presents a challenge, since it’s difficult to predict how things will develop once restrictions are lifted—“but the endeavour should be to restore normality as soon as possible.”

Gen Malik says that while CAPF strength has gone up in Kashmir, the volume and density of army presence has stayed static at earlier levels. The intensity of military action against militants is likely to remain low, he feels, since the army acts mainly on intelligence from the local police. “As the local police is preoccupied with maintaining law and order, the information flow has gone down. Also, the army has been freed of the Amarnath Yatra duty since it has been called off,” he explains. The army—stationed mainly on the border and LoC—is called in mostly for specific operations against militants.

The CRPF, however, is already stretched thin. Remember, even as the largest CAPF, it is essentially a police force. And yet, it finds itself right in the thick of action in high-stakes security situations. Besides Kashmir, the CRPF is also the mainstay in the fight against left-wing extremism; it also plays a crucial role in ensuring free and fair elections. With assembly elections due in Haryana, Maharashtra, Jharkhand and Delhi in the next few months, CRPF personnel will need to be deployed in the poll-bound states.

NSA Ajit Doval landed in the Valley on August 5.

The present heavy deployment in Kashmir is understandable, says former BSF director general Prakash Singh, since the government did not want to take any chances. But he feels the levels should be gradually brought down after carrying out an assessment on the ground. Singh, who has also served as DG of Uttar Pradesh and Assam police, is worried about places from where additional companies have been withdrawn for redeployment in Kashmir. “These additional forces were definitely not sitting idle in those zones, maybe Maoism-hit areas or the Northeast. I am amazed that so many men could be withdrawn,” he tells Outlook.

Counter-terrorism expert Ajai Sahni doesn’t agree—in his view, left-wing extremism has been largely controlled over the past few years. “The number of affected districts has come down from 223 to 60. The pattern of insurgency in the Northeast has also changed. The situation has improved considerably and fatalities have gone down. Even in Kashmir, the situation has improved from a security point of view, with major incidents of terrorism becoming limited to a few tehsils,” he tells Outlook.

Security is an imperative unto itself, in his opinion—and must be treated parallel to other issues, and those needs met. Central security forces have been in Kashmir for the past 30 years, he points out, and can continue to be there for another 30, even indefinitely. “There’s nothing problematic about that from the security perspective. You can question the Kashmir move on policy or strategy, but not security,” he says.

However, Prakash Singh raises the question of training. “Ideally, one out of seven companies that comprise a battalion should always be under training so that the men remain fighting fit and motivated. Also, before sending men into a new place—Chhattisgarh or Kashmir—they should be given at least a month-long pre-induction training to familiarise them about the place and its problems. That’s not being done. There’s too much ad-hocism,” he adds. Lack of local sensitisation is precisely what can bring about incidents that are ultimately counter-productive.

A senior CRPF officer, who wishes to remain unidentified, admits pre-induction training is being given a miss. What’s prescribed is a six-week-long targeted familiarisation before men are sent to Kashmir, Maoist-hit areas or the Northeast, he says. “There’s no time for it. Also, the men who have been sent to Kashmir may have to stay there for months together since there are no companies to spare, either for rotation or rest and recuperation,” he adds.

The CRPF officer too admits security presence had to be boosted in the run-up to the Article 370 announcement, so as to preclude a 2016-type mass upsurge. “At that time, things happened suddenly and the forces were not prepared to deal with it. Also, there was much less force then and no clear intent to act against protesters. It’s not the same this time. The forces are well-prepared. We have orders to quell any protest before it gets out of hand. There is a decisive government, both at the Centre and in Jammu and Kashmir,” he says.

When can the deployment levels be reduced? He’s not sure. There will be logistical problems once the winter sets in, he admits, as proper arrangements will have to be made for the additional forces if they continue to be there post-October. “The men cannot live in tents. They need permanent accommodation, comfortable quarters and bukharis (wood stoves) to keep them warm. All that will need to be arranged.”

Lt Gen. (retd) Syed Ata Hasnain, who headed the army in Kashmir during 2010-12, also reflects on the past flare-ups whose handling left a lot to be desired. He says lessons have been learnt in 12 years. “The government and the forces now know the strategy of separatists, terrorists and also Pakistan. A lockdown has not happened for the first time. Earlier there were unplanned ones, like after the 2008 and 2010 protests. Even the post-Burhan Wani protests went out of hand because the CRPF was not there in the rural areas where violence had erupted. The army was somewhat soft,” says Lt Gen. Hasnain.

By contrast, for him, the way Kashmir has been completely transfixed this time speaks of a desirable degree of control. “All areas, urban and rural, are covered by security forces. All networks working against the government have been targeted. It’s not just a militaristic affair, but a complete systems approach.” He too believes the additional deployment is sustainable for a long term. Says the veteran: “I personally don’t think much is going to happen. However, we need to keep the forces to cater to the eventuality of a big event, like a Pulwama-type IED blast or a terror attack. Then the situation can be somewhat unpredictable and even a limited war is within the realm of possibility.”