There is a business opportunity lurking in every circumstance. This summer, Bangalore-based start-up PathShodh was all set to launch a device that could carry out eight different tests to monitor chronic health conditions--culmination of a decade’s research. Then the lockdown happened and, like everything else, the event had to be put off. What was more frustrating, says co-founder Vinay Kumar, was being shut off from their laboratory at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). But that enforced idleness triggered a brainwave—why not add COVID-19 diagnosis to the gadget’s array of paper-strip tests?

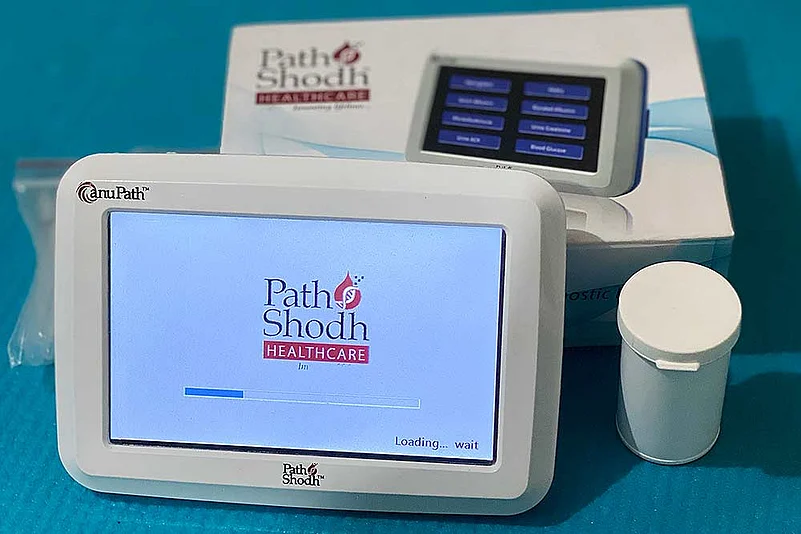

Pathshodh’s device, called Anupath, aimed to fill a gap in disease management—a solution as handy as a glucometer but which could do more than just read out blood glucose levels. And reach rural areas that don’t have access to sophisticated medical machinery. Anupath’s paper strip tests have been designed for five blood tests—HbA1c (glycated hemoglobin), glycated albumin, blood glucose, haemoglobin, serum albumin and three urine tests—microalbuminuria, urine creatinine and urine ACR. It covers, at one go, diabetes, anaemia and kidney disease.

“If somebody is Covid positive and hospitalised, these vitals are also very critical,” says Kumar. Now, Pathshodh is adding a COVID-19 antibody test and an antigen test to the device; just like the others, these involve disposable paper strips coated with a proprietary sensing chemistry which are inserted into the handset-like device and analysed using an electro-chemical signal. The aim, he says, is to diagnose for Covid and simultaneously manage other conditions like diabetes. ”So, within minutes we can get these results.” In July, the start-up received a grant from the Department of Science & Technology (DST) to develop the COVID-19 antibody test. Apart from analysing and displaying test results on its screen, the point-of-care device will be able to store up to one lakh test reports along with patient information. “We hope we can go for the final validation early next month,” says Vinay Kumar.

Ayu devices’ digital stethoscope splits it up, and uses bluetooth and a mobile phone for a wireless instrument for doctors

Like Pathshodh, many start-ups now have Covid in their cross-hairs. “Most start-ups offering Covid solutions have re-purposed their existing technology,” says Poyni Bhatt, chief executive officer at the IIT Bombay incubator, Society for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (SINE). There’s a combination of both deep-tech and quick-turnaround products—like personal protective equipment which range from low-tech masks to anti-microbial coatings. Also, diagnostics, informatics, devices, all the way to ventilators. Take SINE start-up Ayu Devices which makes digital stethoscopes—two years ago it had developed a device, Ayu Link, which featured a module that sat in between the chest and ear piece of a regular stethoscope to amplify heart and lung sounds. Doctors typically acquire a keen ear from long years of experience, explains founder Adarsha Kachapilly. But given the doctor-patient ratio in India, the start-up saw a gap it could fill—besides amplifying the sounds, the device also has them recorded, shared and analysed. In the next version, it added blue tooth connectivity.

With COVID-19 however, a totally different problem cropped up—doctors were finding it difficult to use their stethoscopes while wearing a protective suit which covered the ears. So, Ayu Devices split the stethoscope up, connecting the chest and ear piece via blue tooth—the physician could now plug in an earphone set which was connected to his mobile phone which, in turn, was wirelessly connected to the chest piece in his hand. Hence, it can be used even when there’s a partition between doctor and patient, says Kachapilly, an electrical engineer who quit his job at L&T in 2015 to work on the technology at an IIT-Bombay lab. “Whenever he clicks on the device,

it directly streams (sounds) to his ear,” he adds. “We have a patent published in over 60 countries for the device and it’s in the final grant process,” he tells Outlook. A year ago, says Kachapilly, the idea was a bit unconvincing—after all, why would a doctor want to use blue tooth capability in a stethoscope. “Now, that’s become the main part of the product.” But the pandemic also presents a practical difficulty—since supply chains have been disrupted, the company has to find ways to increase output. “We are able to make five units a day but we need to make more. We are getting so many orders,” says Kachapilly.

Shanmukha Innovations’ mobile labs pack in an RT-PCR machine and will be deployed in affected zones

How much of a delay these supply disruptions would have on start-ups remains to be seen, says C.S. Murali, chairman of the entrepreneurship cell at IISc. “But the good news is that companies were working on products which they could repurpose to address the Covid situation. “Therefore, those companies immediately shifted gears,” he tells Outlook. The IISc’s Society for Innovation and Development (SID) can count up to seven such start-ups. For instance, General Aeronautics, which was working on drones for agricultural spraying, flew disinfection sorties for the Bangalore municipal authority and surveillance flights for the police in Covid containment zones during the lockdown. “Based on that, we got a call from Odisha where we did three-four cities,” says founder Abhishek Burman. But the actual opportunity could be opening up in their focus area of agriculture, he reckons. “The primary challenge was to convince the farmer to use the technology. Perhaps it would become easier now because there is a pressing need,” says Burman, pointing to the grim agricultural labour situation.

Shanmukha Innovations, also from SID, had been working on portable instruments for the past three years. In March, the company swung its focus around to designing a mobile lab for RT-PCR tests. The current turnaround time of these tests is between one and five days, says chief executive Arun B. “If we have mobile labs which can be deployed closer to containments zones or regions with more cases, we can cut down the overall turnaround time.” So, they transferred the laboratory workflow into three separate vans—these processes involve aliquoting and neutralising the virus, extracting its RNA and then loading it into the RT-PCR machine for analysis. Since the actual machine is expensive, the alternative they are working on is to deploy the easily available thermal cycler—used in most research labs for DNA amplification—along with a flourescence reader. “The combination of the thermal cycler and reader would be equivalent to an RT-PCR instrument,” says Arun. The first outfit is ready to be handed over to the Bangalore Medical College, he says. The task ahead for the start-up is to get private testing labs and state governments interested in their mobile solution.

Anirvan Chatterjee of IIT-Bombay’s Haystack Analytics puts things into perspective. “There are two things which characterise a start-up. They have technology which is very new and which is ready. Secondly, they can move very quickly.” His company specialises in genomic analysis and has been working on tuberculosis. With COVID-19, Haystack began mapping the disease transmission, using the open source platform Nextstrain. “From end-March we have been tracking this,” he says. Take, for instance, a region dealing with its first cluster of cases. Genomic analysis of patient samples can help map where the newer infections probably came from, so that health authorities can factor those into their containment efforts, explains Chatterjee. For a given location, such as a factory, the genomic analysis can suggest whether the disease transmission happened on the premises or whether the cases came in from different locations, he says. “What we say is, we are enabling the Unlock,” explains Chatterjee. “When we hear about somebody testing positive, invariably the first question is where did that person get infected from.” The cost of the genomic sequencing for a Covid sample was somewhere around Rs 25,000-30,000 in March-April, he says. “By May, we had been able to bring it down to Rs 7,000 and now we think we can do a Covid whole genome for about Rs 2,500,” he says. Haystack Analytics is another start-up that has funding support from DST. Currently, clinical validation is on and a pilot test will follow.

“These have been days of huge learning and it continues to be,” says Anita Gupta, head of innovation and entrepreneurship at the Department of Science and Technology in Delhi. In April, the DST set up the Centre for Augmenting WAR with COVID-19 Health Crisis (CAWACH) to scout for innovations that address coronavirus challenges. Of the 836 applications that came in, around 54 start-ups have been shortlisted for funding--the total CAWACH corpus is Rs 56 crore. “Everywhere, it is the power of collaboration that we are totally relying on. And it has delivered as well,” says Gupta, pointing to how the incubator network across the country has been roped in for the project.

There are other government agencies, too, working with start-ups. “I’m pretty hopeful we’ll come out with at least 100 solutions collectively,” says Gupta. “All these solutions will have a clear market for the next one year at least and some will have global potential. We have to tap the most promising ones and link them up with the right set of people.”

India’s start-up community of venture capitals, founders and mentors, too, has a parallel effort going, via a Rs 100 crore Action COVID-19 Team (ACT) grant—so far, around 48 projects working on a COVID-19 application have been funded. Clearly, there’s a lot of activity in tech circles. As Anita Gupta puts it, “Now is the time to showcase real action.”

By Ajay Sukumaran in Bangalore