After initiating the discussion with chief ministers on handling the nationwide lockdown and making his opening remarks on April 11, PM Narendra Modi handed over the proceedings to home minister Amit Shah to moderate. Though Centre-state relations come under the purview of Shah’s ministry, the CMs were taken by surprise when he took charge of the video conference. He had been present in their earlier meetings with the PM too—on March 20 and April 2—but except urging the states to implement the lockdown strictly at the second meeting, Shah had mostly been silent. Much like the other two ministers participating in the meeting—defence minister Rajnath Singh and health minister Dr Harsh Vardhan, along with the principal secretary to the PM, the cabinet secretary, the home secretary, the health secretary and the DG of Indian Council of Medical Research.

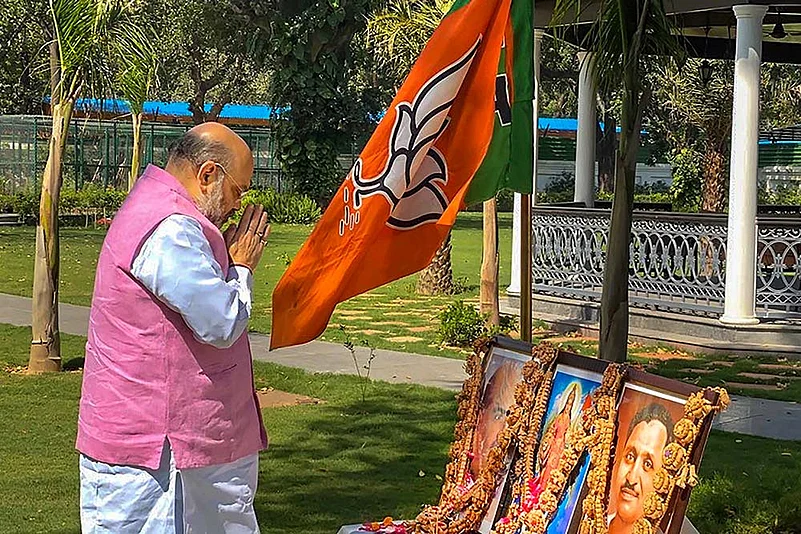

Asking Shah to moderate the meeting would not have been seen as significant in the normal course as his ministry is at the forefront of enforcing the lockdown and coordinating with the states. However, it raised some eyebrows because Shah, known for his hardline image, had somewhat receded into the shadows after the back-to-back decisions to abrogate Article 370, pushing the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and to amend the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. His uncharacteristic reticence since riots broke out in Delhi in February was being talked about within the BJP and also among Opposition leaders. Congress leader Kapil Sibal had questioned his silence, tweeting on March 28 that while people were locked down and lakhs of migrants were walking home, the home minister was neither seen nor heard.

“Not much should be read into Shah moderating the conference,” says a senior government functionary. “Had somebody else been the home minister, it would have been the same as the ministry of home affairs is central to the lockdown. Whether it is issuing instructions about ensuring essential goods and services or issuing advisories regarding welfare of migrant labourers, it is all done by the MHA. Shah’s presence was crucial at the PM’s meeting with the CMs.”

Pointing out that it’s the work done by ministers, not their visibility, that is important, the functionary adds: “Shah is visible in the Centre-states conference. You see Rajnath Singh, as No. 2 in the government, chairing a meeting of Group of Ministers; (external affairs minister) S. Jaishankar coordinating efforts to get Indian students back from Wuhan; (finance minister) Nirmala Sitharaman announcing an economic distress relief package; (I&B minister) Prakash Javadekar briefing the media about important cabinet decisions; Dr Harsh Vardhan coordinating COVID-19 mitigation efforts; (food and public distribution minister) Ram Vilas Paswan ensuring availability of essential food items; (road transport and highways minister) Nitin Gadkari looking at ways of getting labour back to restart highway projects; and (agriculture and rural development minister) Narendra Tomar trying to figure out a way to harvest the rabi crops.”

But the general perception remains, especially with political rivals, that Shah is no more the first among equals, next only to the PM? A senior BJP leader, not wanting to be named, says it was only a perception due to his old association with the PM, and that needs to change. Apparently, the BJP’s ideological parent, the RSS, had also expressed reservations about this. “The perception was harming the party,” says a senior RSS functionary. “The BJP is a disciplined party and does not function like other parties. The hierarchy in the council of ministers needs to be maintained. If Rajnath Singh is No. 2, he has to be seen as such. And the other ministers too need to get their due. Whenever Modi goes to the BJP headquarters, he goes like a karyakarta (party worker), giving the party president due respect and taking a backseat himself. Ministers cannot forget this discipline as they are karyakartas first.”

An MHA official claims the home minister is closely monitoring all pandemic-related information from his Krishna Menon Marg residence. “Shah continues to be as important as ever. Some niggling health issues are keeping him away from the warfront. He has been to his office in North Block a few times and attended a few GoM meetings, but generally works from home,” the official adds.

Bureaucracy to the Forefront

Subtly but definitively, the COVID-19 crisis has changed the way government works. While it has highlighted the role of respective ministers, it is the bureaucrats who have become the face of the government’s fight against the pandemic. “While the Prime Minister’s Office remains firmly in the saddle, it is the colonial-era public administration system that has become the mainstay of the fight against the novel coronavirus, while the PM is strengthening his image as a benign ruler by reaching out to doctors, nurses, health and sanitation workers through his Mann ki Baat,” says a secretary to the government of India. Leading the charge on the ground are officers at the district level—district magistrates, superintendents of police and chief medical officers. As the PMO has assigned individual states to all Union ministers, they get daily reports bypassing the lengthy state-to-Centre channel. The respective ministers coordinate with all the DMs, SPs and CMOs of the state on a daily basis regarding measures taken to contain the spread of COVID-19, quarantine facilities and lockdown-related problems, and report back to the PMO. There is a dedicated email address, accessed by the ministers concerned, where they get constant updates to be passed on to the PMO.

“The PMO is depending on multiple layers of information sources to keep tabs on how things are unfolding on the ground in terms of outbreak, hotspots, containment and problems like supply of essentials goods,” says the secretary. “The mechanism has cut down on reaction time and slip-ups. We are also getting success stories from districts like Bhilwara and Agra, which are being used as case studies for others to emulate. The credit for these small victories goes to the local administration.”

The PM’s team is led by his principal secretary P.K. Mishra, a 1972-batch Gujarat-cadre officer, in close coordination with principal advisor P.K. Sinha. “Between the two PKs, it is clearly Mishra who is boss. Associated with the National Disaster Management Authority in its initial days, he has vast experience in disaster management. He was also conferred with an award by the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction last year. He is definitely the right man for the job,” claims a senior official.

The backbone of the core team is cabinet secretary Rajiv Gauba, a 1982-batch Jharkhand-cadre officer. He is believed to be the operations man, coordinating with various ministries, states, bureaucrats and other agencies, and taking key decisions in the fight against COVID-19. Then there is the ring formed by secretaries in key ministries, including health, finance, external affairs, defence and home. Though all of them are working around the clock, health secretary Preeti Sudan and home secretary Ajay Bhalla have perhaps the toughest jobs at hand. A 1983-batch officer of the Andhra Pradesh cadre, Sudan is usually the first point of contact for any queries coming from the PMO or her ministry. She is also involved in regular review of the preparedness of states and Union territories in terms of requirements like testing kits, PPEs, masks, ventilators and even hand sanitisers.

Bhalla, a 1984-batch Assam-Meghalaya-cadre officer, is coordinating all lockdown-related issues with the states from a ‘control room’ set up in the North Block. He monitors the work of two key teams working under him—one collates all pandemic-related data from the health ministry and various states and compares it to the global figures, and the other tackles issues raised by the states and the problems faced by them. All lockdown-related advisories, notifications and guidelines to states and other ministries are sent out by Bhalla.