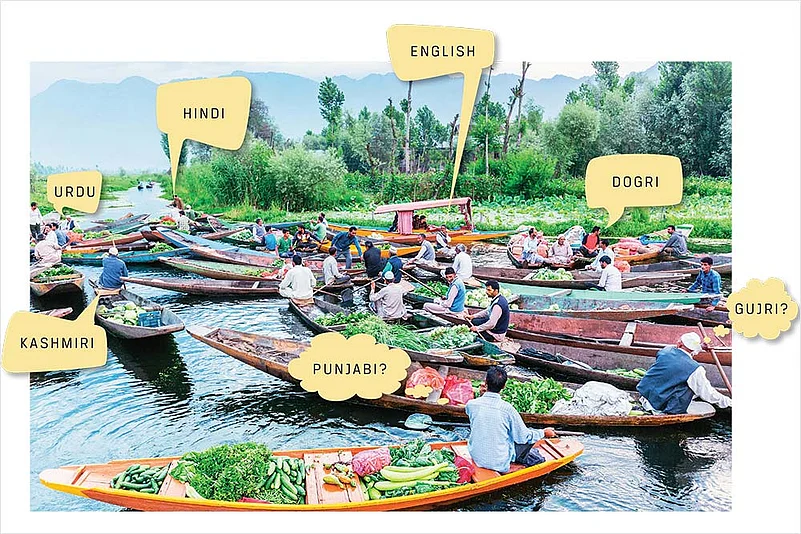

Those who heard the news may have been struck by one fact: Kashmiri was not an official language in J&K till now. A second pang of surprise: neither was Dogri, the major language of Jammu. Both those gaps have been filled now with the Jammu and Kashmir Official Languages Bill 2020, approved by the Modi cabinet on September 2, and passed by a voice vote last week in the Rajya Sabha. But as this new regard for native linguistic legacies was celebrated (albeit selectively) in hoardings put up by the BJP across Jammu, the name of another language also caught the eye: Hindi. In all, there are now five official languages for one Union Territory: Urdu, Hindi, Kashmiri, Dogri and English. Don’t let that designation as ‘UT’ mislead you. Because, ‘what exactly does this policy mean?’ is a question you could ask in these parts in a dozen mother tongues—conservatively speaking. This is a policy, therefore, that could also have a domino effect in other regions of high linguistic diversity, like the Northeast: imagine the explosive situation that may ensue if all languages of Assam, Nagaland or Arunachal Pradesh demand official language status!

How will five official languages work anyway? Well, almost no policy in this erstwhile state is ever designed for reasons of pure administrative efficiency—politics is never absent from the ensemble of factors that guide J&K’s twisted destiny. Hoardings that say the law has ‘restored the honour of Hindi and Dogri’ are a curious pointer—not least for the implication that Hindi’s honour was somehow at stake in this northern, mountainous terrain. On cue, Union MoS Home G. Kishan Reddy said: “The Bill fulfils the decades-long wishes of the people of the region.” And the BJP in Jammu was quick to link it with the revocation of Article 370, with Union minister Jitendra Singh, a Jammu native, saying as much on Twitter.

Why does Hindi enter the frame? Because of the status its Siamese twin, Urdu, enjoyed. Before the revocation of Article 370, Urdu was the official language of J&K—even if official communication was mostly conducted in English. Now reduced to just one of five official languages, the BJP government has ended Urdu’s 131-year reign as the only official language of the ethnically diverse Jammu and Kashmir region.

How was Kashmiri never that? And how come Dogri was missing, even though it was a Dogra king who instituted the previous policy? That relates, at one level, to J&K’s very complex linguistic life on the ground. Even after Ladakh was hived off as a separate UT last August—along with its stock of Tibeto-Burman languages—the left-over province is still a zone of very high linguistic diversity. In the main, it has a mix of sub-families under the larger Indo-Aryan language umbrella: those once grouped under ‘Dardic’ (like Kashmiri and Shina) in the Valley, and members of the Western Pahari group (like Dogri) in Jammu, among intermediate forms and others like Gujri—as also the Punjabi and Mirpuri (which falls under a different group across the LoC, also called ‘Pahari’) spoken by old settlers and Partition refugees.

Confused? Well, the pre-Partition kingdom of Kashmir was even more robustly vibgyor, including a full complement of the very many lects of what was often called ‘Outer Indo-Aryan’ (sometimes hypothesised to belong to a pre-Vedic branch), now dispersed across PoK and Gilgit-Baltistan. A bewildering array that steered Kashmir’s language policy towards one integrating form. In 1889, Maharaja Pratap Singh, the third ruler of the Dogra dynasty, replaced Persian with Urdu as the court language. “He had no love for Urdu but, an intelligent ruler, he understood its immense benefit,” says Prof Shohab Inayat Malik, head department of Urdu at the University of Jammu. “From Jammu to Jhelum Valley (in PoK), Urdu bound people together. And the Maharaja knew it. The language helped the Dogra rulers consolidate the vast, diverse region into one unit,” says Prof Malik.

After Partition, Urdu remained a means for inter-community, inter-region and also official communication—although slowly relieved of the latter duty by English after All India Services were extended to J&K in 1962. As non-local officers of the IAS and IPS started working in J&K, they naturally preferred English. Urdu had a lingering official life, though. It’s the language of land and revenue records and the courts, in particular the lower judiciary and the police. FIRs are written in Urdu. It’s also the mode of instruction in government and private schools all across Jammu and Kashmir.

Sikhs demand Punjabi as an official language in J&K.

This had, in recent times, bred some resentment among the Dogra community. That’s why figures like Prof Lalit Magotra, who had been fighting for long to popularise Dogri, are happy with the move. A language spoken by about 5 million people, endowed with distinctive features like tone, a literary legacy and the now-defunct Takri script, Dogri received Eighth Schedule recognition only in 2003. But it was a matter of simple exigency, back in the late 19th century, when the Dogra king opted for Urdu from the northern Indian plains as the link language (while the royalty itself spoke Dogri). In undivided Kashmir, the different ethnicities would speak Kashmiri, Mirpuri, Gujri, Ladakhi, Dogri, Balti, Punjabi and many others as their mother tongues but no one had issues with Urdu, says Prof Malik. The latest move to introduce five official languages would actually create a deep linguistic divide, he says.

The division is already visible. Gujjars of the region—whose language, Gujri, is said to be more akin to Rajasthani—are angry. The pastoralist community, a Scheduled Tribe in J&K, are part of a nebulous group spread all over north India and Pakistan—the language has well over two million speakers, including in Afghanistan, and can be said to be one that has the most widely dispersed presence in J&K because of their reliance on traditional pastoral transhumance with their livestock. Javaid Rahi, head of Tribal Research and Cultural Foundation (TRCF), says Gujri deserved the honour precisely because of this unique pan-J&K reach—which include parts of the Valley and much of Jammu. “You cannot ignore it and we will not rest till it is included in the official languages,” he adds. They have now made representations to Gujjar leaders elsewhere in India to rally behind them.

Unlike in the more homogenous central part of the Valley, the linguistic fault-lines are more visible across Jammu’s own tracts: a vast majority in the Pir Panjal region and Chenab Valley speak languages related to Kashmiri (like Kishtwari, Poguli) and various Western Pahari languages like Bhaderwahi, Sarazi, even a spillover of Gaddi from Himachal. All of this besides Urdu and Kashmiri. The West Pakistani refugees speak Mirpuri. In three districts where Dogras are in majority, Dogri is spoken along with Hindi. So if the favouring of one over many others was the skew that was sought to be removed, the new law has only introduced a few extra skews into an already fraught polity. It’s only given to a few, though, to have the political heft to demand parity. Sure enough, the All Party Sikh Coordination Committee chairman and J&K Apni Party leader Jagmohan Singh Raina described the exclusion of Punjabi from the Bill as an ‘anti-minority’ decision. They have taken the issue to Parliament. Congress MP Manish Tewari too called for an end to the ‘discrimination’ and urged the Centre to designate Punjabi as an official language in J&K. He argued that Punjabi was spoken prominently in Jammu since the domination of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in the region, and that many refugees who came to Jammu after Partition spoke Punjabi. A signature campaign is now on.

Prof Hari Ohm, former dean, Social Sciences University of Jammu, foresees only complications. “You will not see anywhere in India that any state or any Union Territory has five official languages,” he says. Since Partition, many “illogical and unreasonable” steps have been taken for the emotional and political integration of Kashmir and Jammu regions, he says, but in vain—“integration never took place and things got more complicated.” The government couldn’t outright replace Urdu with Hindi fearing a backlash from the Valley, thus came up with the five-language formula, he feels. Of late, some sections in Jammu have sought to link Urdu with ‘Pakistan’. This May, Daily Excelsior, an English daily from Jammu, carried a column that tauntingly asked the Centre whether it wished to retain “this last icon of Pakistan’s national language” as a “victory symbol for radicalised jihadi elements.” Urdu, of course, is as ‘alien’ to Pakistan as it is to J&K—being a central Indo-Aryan language.

Prof Ohm sees no benefits flowing to Kashmiri or Dogri. “What will happen now is that Hindi, English and Urdu will be used for official communication and Kashmiri and Dogri will have the same status as they had so far.” A former minister described the decision as a charade that inserts a new problem where there was none. “It’s like L-G Sinha will issue directions in Hindi, among his advisors K.K. Sharma will formulate guidelines in Dogri, Farooq Khan in Urdu, Rajiv Rai Bhatnagar will follow up in English and Baseer Khan will propagate it in Kashmiri. This is BJP’s concept of Naya Kashmir!” National Conference MP Hasnain Masoodi feels the real objective is to introduce Hindi. “The bill was conceived to formalise Hindi and marginalise Urdu. Its authors know well that five official languages would be impractical,” he says. “No benefit will come to the two regional languages.”

By Naseer Ganai in Srinagar