The Centre has repealed a dozen laws of the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, and amended 14 others through two executive orders. Now any Indian citizen can buy and sell land in the Union territory of J&K. Supporters of the central government’s moves are celebrating the notification of the two orders—Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation (Adaptation of Central Laws) Third Order and the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation (Adaptation of State Laws) Fifth Order, 2020—as steps towards ‘full national integration’. In contrast, millions of J&K residents, including displaced Kashmiri Pandits, are hearing the death knell of J&K’s demographic profile, culture and traditions in this loss of constitutional and legal protections, even as similar protections continue to be in force in nearly a dozen other states. The Constitution’s Sixth Schedule and Articles 371, 371A, 371B, 371C, 371F, 371G and 371H grant wide-ranging autonomy rights to the provincial governments and people of the Northeast on ownership of land and other resources, among other issues.

In fact, over the decades, governments in the Northeast have imposed additional legal restrictions on real estate transactions even within local populations—between tribals and non-tribals. For example, during Pawan Chamling’s stint as Sikkim CM, the state government brought in laws mandating that the Limboo and Tamang tribes can only sell land within their community and even placed a blanket ban on sale of land by those who own less than three acres. While the Chamling government repealed laws that prevented women marrying outside Sikkim from inheriting ancestral property within the state, they are still not allowed to bequeath such inheritance to their children.

ALSO READ: Laws Of Their Land

Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand too have laws restricting real estate transactions by non-domiciles. Section 118 of the Himachal Pradesh Tenancy and Land Reforms Act, 1972, for example, debars all non-agriculturists from buying land in the state. There are also a slew of restrictions on the quantum of land non-domicles can purchase in notified urban areas as also the purpose for which they may do so.

The Centre has projected the opening up of J&K’s vast land bank to ‘outsiders’ as a way to usher in development, with the new land laws seen as a corollary to the abrogation of Article 370. While the end of J&K’s hollowed-out autonomy was said to benefit Jammu residents more than their Kashmiri counterparts, with the former riled by the lifting of restrictions on real estate transactions, a sense of being betrayed by the political masters in New Delhi now seems to bind Muslim-majority Kashmir with Hindu-majority Jammu.

“The new land laws would operate more harshly against the Dogra land of Jammu than against Kashmir,” says former minister and chairman of Panthers Party, Harsh Dev Singh. If Kashmiris fear that the new laws would turn the pristine Valley into “another Palestine”, Singh believes outsiders would prefer to acquire land in Jammu due to persistent disturbances and security threats in Kashmir. “The locals would not only be persuaded and seduced to part with their lands, but the outsider influx in Jammu would also pose a threat to Dogra culture and identity,” adds Singh, who dismisses claims by the Centre that the new laws will bring in incremental investments and better employment prospects to Jammu.

“Was there really any restriction that stopped outsiders from investing and setting up industries in J&K in the past?” asks the panthers Party chairman. “Several outsiders have set up huge industries at various places, including Kathua, Samba, Jammu and Udhampur, but chosen to employ skilled and unskilled labour from other states instead of providing employment to locals.”

Among the casualties of the new central notifications is the J&K Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, 1950, which had ushered in unprecedented land reforms in Kashmir. Also called the ‘land to the tiller’ law, it placed a ceiling of 22.75 acres on individual land holdings. Land exceeding this limit was transferred to the tiller without any compensation to the landlord—this is what made the land reforms in J&K unique in India. Through this law, a staggering 7.9 lakh landless peasants, including 2.5 lakh dominated-caste Hindus of the Jammu region, were conferred proprietary titles to land. In 1976, then J&K CM Sheikh Abdullah enacted the Agrarian Reforms Act to further rationalise land ownership in J&K. This law too has been repealed now.

The BJP claims it was necessary to do away with the earlier laws in order to industrialise the region. Party leader and former president of High Court Bar Association, Jammu, Abhinav Sharma, says the Big Landed Estates Abolition Act prevented industrialists from owning large landholdings needed to set up projects. The justification for new land laws proffered by BJP leaders and the administration, however, cuts no ice with political rivals. Congress spokesperson and leader from Jammu, Ravinder Sharma, says the BJP is all for protection of land and jobs in Himachal and other states, but its priorities are different in the case of J&K.

What has got J&K’s people worried even more are the new domicile laws that the Centre passed through another executive order in March, despite Union home minister Amit Shah’s earlier assurance of there being no measures on the table that could alter the Union territory’s demographic profile. Through this executive order, domiciles have been defined as those who have resided for a period of 15 years in J&K, or studied for a period of seven years and appeared in Class 10 or 12 exams from an educational institution there. This makes it easier for ‘outsiders’ to claim domicile in J&K. The Centre also amended the J&K Property Rights to Slum Dwellers Act by deleting references to “permanent residents” and enabling non-local slum-dwellers to gain property rights in Kashmir. “Some BJP leaders promised to enact suitable laws like those in Himachal Pradesh to save the lands of people. Others made tall pronouncements of providing constitutional safeguards. Everything proved to be a hoax,” says Singh.

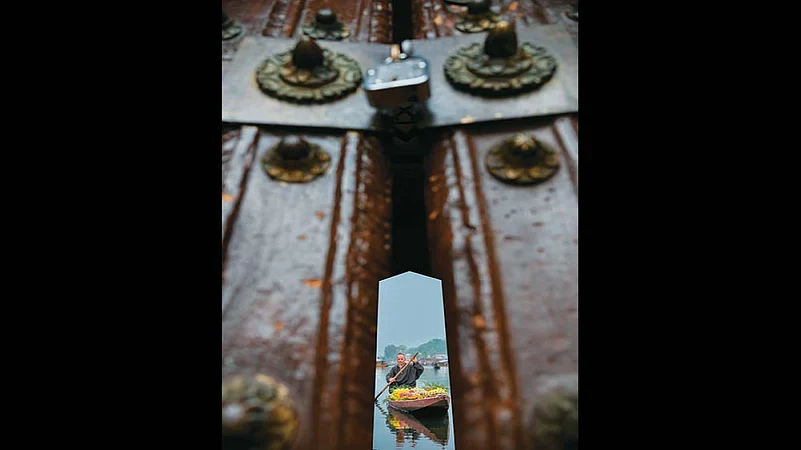

Police detain PDP activists during a protest against new land laws in Srinagar.

In fact, the only ones rejoicing at the thought of buying a piece of land in Kashmir are ‘outsiders’. But, in states with similar legal safeguards over land-owning rights, the mere mention of diluting such provisions evokes strong disapproval. Already agitated over fears that the Citizenship (Amendment) Act will lead to altering the cultural and ethnic identity of the region, civil society groups and political leaders in the Northeast have been vocal against any plan to dilute Article 371 ever since the abrogation of Article 370.

In Himachal Pradesh, even though successive state governments have progressively opened up the local land bank to non-Himachalis, any overt indication of diluting the special tenancy laws meets with strong public disapproval. This disapproval cuts within too as the state’s Tenancy and Land Reforms Act, 1972, also makes real estate transactions between non-agriculturist and agriculturist Himachalis difficult. In fact, when Ganesh Dutt, a former BJP vice president in Himachal, welcomed the new land laws for J&K, it triggered a sharp response from Prakash Lohumi, a veteran media professional in the state. Lohumi told the BJP leader that for “non-agriculturist Himachalis, it is now easier to buy land in J&K than in Himachal Pradesh”.

The issue of revisiting Himachal’s tenancy laws has been in a limbo for decades. In 1997-98, recalls Dutt, as the BJP’s in-charge for the hill state, Narendra Modi had “formed a party panel to get public feedback and suggest solutions” for simplifying the state’s tenancy laws. The plan was quickly abandoned after it was clear that any dilution would outrage the public. Over a decade later, the state’s BJP government under Prem Kumar Dhumal, which seemed amenable to opening Himachal’s land for rapid industrialisation by ‘outsiders’, was voted out in 2012 after the Congress launched its ‘Himachal on Sale’ offensive.

More recently, CM Jai Ram Thakur’s plans to simplify the tenancy laws in order to attract global investors too met with angry reactions from the Congress and the public. “We will not allow the sell-out of Himachal’s land to capitalists and land sharks in the garb of investments,” says leader of Opposition Mukesh Agnihotri. With Congress on the offensive and Thakur on the backfoot, Mohinder Singh, the state’s revenue minister, has been vociferously canvassing the importance of Section 118 of the Tenancy Act. “There is no plan to tweak Section 118,” says Singh, while clarifying that the legal framework in the state “doesn’t put non-agriculturists or potential investors at any disadvantage” as long as they stick to the rules for purchasing land and get the necessary clearances.

The land laws in Himachal allow non-domiciles to buy land up to four acres for horticulture or agriculture, 500 sq m for residential and 300 sq m for commercial purpose after they get requisite permissions from the revenue department. The state cabinet is also empowered to make other concessions on a case-to-case basis. Such discretionary powers explain how non-Himachalis like the late former PMs Atal Behari Vajpayee and I.K. Gujral or Congress leader Priyanka Gandhi Vadra managed to build sprawling bungalows in the state.

Besides enabling ‘national integration’, the other running theme in the BJP’s bid to open up the land banks of J&K for outsiders is that the new laws are necessary to infuse investment, create jobs, urbanise the region and prevent any secessionist activity. It is, perhaps, pertinent to wonder whether the states in the Northeast, most of which fare poorly on the indices of investment or employment, and have had a history of secessionist movements, figure in the BJP’s grand plan for national integration and development. Similarly, if easing real estate transactions ushers in economic renaissance, why would the BJP, which rules both Himachal and Uttarakhand, not dilute the land laws in these states? Or is the Centre simply telling the people of J&K that their right to their lands is now a matter of history?

By Naseer Ganai in Srinagar and Ashwani Sharma in Shimla