Assam was the first state to erupt in protest against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act. It was also the first, and so far, the only, state to go through the exercise of the National Register of Citizens. However, protests there have been only against the CAA, not the NRC, despite agreement over the fact that the exercise, which left out 19 lakh people, was deeply flawed. This is because the primary emotion driving anti-CAA protests in Assam and the Northeast is fear of the Bengali Hindu. For us Bengalis from the region, this is unsurprising. The experience of being unwanted citizens in our own country is one that three generations of Bengalis, Hindu and Muslim, have lived with in Northeast India.

At Partition, most of the Sylhet district of undivided Bengal, an area of Bengali habitation, went to East Pakistan in a controversial referendum. Bengali Hindus from there became refugees. Many of them migrated to what had until then been part of the same province, but now a part of Assam and India. There, they found themselves unwelcome. Refugees who survived Partition, were attacked again after reaching what they imagined was safe haven in Assam. This process picked up from 1960 onwards, in riots called the ‘Bongal Kheda’ or ‘drive out Bengalis’ riots. The principal targets were Bengali Hindus.

There is great similarity in language and culture between caste Assamese and Bengali societies. In fact, the alphabet differs by only one letter. Even names are similar, with Bhattacharjee, Goswami, Chakraborty, Dutta, Choudhury and Baruah being surnames common to both communities.

Nonetheless, antipathy towards Bengalis has been the prime mover of Assam politics. Although both Bengali Hindus and Muslims were feared and disliked, middle-class Assamese bore greater antipathy—and greater admiration—for the Bengali Hindu. It was common for Assamese intellectuals to read Rabindranath Tagore long after the hated ‘imposition’ of Bengali on Assam had ended with Assam being made a province of British India in 1874. It was also common for Bengali Hindus to be the first targets of rioting right through the 1960s, and until the 1980s.

Assamese Muslims, who claim to be indigenous, have historically aligned themselves with Assamese Hindus. Bengali Muslims were also persuaded to do the same. They were given the title of ‘new Assamese’. In the end, the worst single riot of the Assam Agitation of 1979-85 was the Nellie Massacre, in which over 2,200 Bengali Muslim men, women and children were hacked to death. The “new Assamese” continued to be called “Miyas” in actual practice. They are Miyas to this day.

Talk of equality and justice in Northeast India! Bengalis living there from decades before Bangladesh’s creation in 1971 are routinely called Bangladeshis. It is forgotten that people and the lands remained where they were; the borders changed. The name-calling is not a mere inconvenience; even the Supreme Court under the Assamese Justice Ranjan Gogoi allowed a category for inclusion in the NRC as “original inhabitants”. It was not defined who could qualify for inclusion in this category. However, it is clear from the final results who were not included. Reports based on information from sources in the administration suggest that of the 19 lakh excluded from NRC, around 10 lakh were Hindu Bengalis, and seven lakh were Bengali Muslims. The ‘Bangladeshis’ had been left out.

The Bengalis who paid the price for India’s freedom continue to pay it even today. The Citizenship (Amendment) Act tries to fool them by promising them citizenship, which they already have. The NRC threatens to take away that very same citizenship and declare them Bangladeshis. In the politics of competitive chauvinisms between ethno-nationalist and Hindutva forces, they are again the football that gets kicked around.

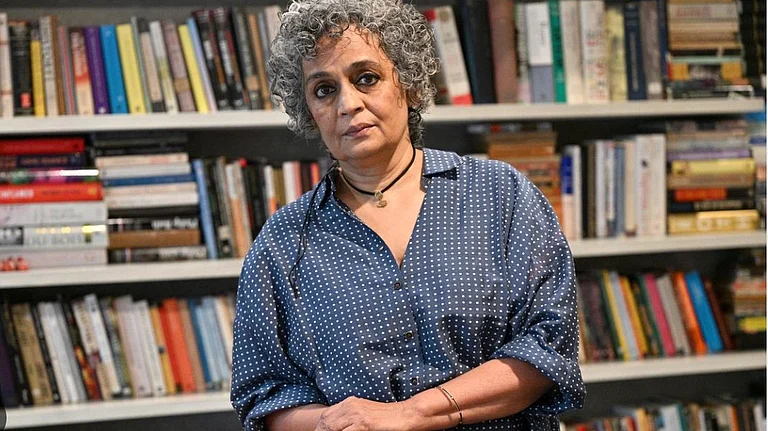

The writer is co-editor of Insider Outsider; views are personal